January

January 1954: Founding of Rochester Methodist Hospital

In 1954, a group of community leaders, drawing upon the values of John Wesley, founder of Methodism, established a new hospital in Rochester, Minn. Two of those early leaders, Gerald Needham, Ph.D., and Mrs. Billie Needham, share their perspectives.

_

The roots of this story date back to the early 1900s. Since 1889, Saint Marys Hospital, located about a mile west of Mayo Clinic, had served surgical patients. Increased demand, however, required more hospital room than Saint Marys could accommodate. In 1907, local business leader John Kahler opened a combined hotel-hospital in downtown Rochester. It offered surgical and post-operative facilities as well as amenities for family and friends who accompanied the patients. Over the decades that followed, the Kahler Corporation developed a network of similar facilities, as well as a nursing school.

After World War II, however, this model was no longer sustainable. The Kahler Corporation shifted to focusing on the hospitality industry and a new, not-for-profit entity, Rochester Methodist Hospital, came into being. Highlights of the history of Rochester Methodist Hospital include:

- For its first dozen years, RMH occupied former Kahler hospital facilities.

- The first successful series of open-heart operations using a heart-lung bypass machine took place at RMH in 1955 with John Kirklin, M.D., and team, attracting national and global attention.

- RMH had the first prominent medical fundraising effort, securing benefactor funds to advance its mission.

- In 1955, RMH established the first hospital auxiliary program in Rochester.

- In 1966, RMH opened a new, state-of-the-art building, named in 1989 for benefactor George M. Eisenberg. This building includes the innovative radial nursing unit that RMH developed and which became a national standard.

- The first FDA-approved total hip joint replacement procedure took place at RMH with the team of Mark Coventry, M.D., in 1969.

- RMH pioneered the concept of unit dose measuring of pharmaceutical drugs, setting a national standard.

- RMH developed a chaplaincy education program that became a national model.

- RMH was a leader in many community outreach programs – car seats for newborns leaving the hospital, “Come and See” to welcome school children, Life Run to promote fitness.

- RMH founded Charter House, an innovative concept in active retirement living.

In 1986, Rochester Methodist Hospital joined with Mayo Clinic and Saint Marys Hospital to form a single organization, a “trusteeship for health.” In 2014, both hospitals united in a single licensure, creating Mayo Clinic Hospital-Rochester, with the Methodist Campus and Saint Marys Campus.

Names and service models have evolved over the years, but the commitment to serving patients remains the hallmark.

February

February 1854: The "Little Doctor" earns his second medical degree

Dated 1854, this is the oldest diploma in the Mayo medical practice.

This commitment to education originated with William Worrall Mayo, M.D. (1819-1911). Standing five feet, four inches in height, he was nicknamed “the little doctor,” but he was a towering figure in terms of his values and dedication to patients. At a time when many physicians had no formal education, he earned two medical degrees – which he received in February 1850 and February 1854. His grandson, Charles W. Mayo, M.D. (1898-1968), said:

“… the up-to-date and exacting Mayo Clinic of today is a reflection of my grandfather’s personal style as a doctor. He was a perfectionist who was readily infuriated by sloppy or second-rate work and was always delighted at any opportunity to improve medicine.”

W.W. Mayo’s passion for education began early. Born near Manchester, England, he lost his father at the age of seven. There was no free public education at the time, and his family was too poor to afford tuition for secondary school and university. However, young Mayo received tutoring from John Dalton, the eminent scientist who established the atomic theory of matter. Dalton, a Quaker, welcomed girls as well as boys to the classes he held; he emphasized the scientific method of inquiry and the merits of individual effort over the privileges of birth.

In 1846, W.W. Mayo immigrated to the United States. He worked briefly at Bellevue Hospital in New York City before moving on to Indiana and, eventually, Minnesota. It was difficult to earn a living on the American frontier and W.W. Mayo held a wide range of jobs, but he always gravitated to medicine.

He graduated from the Indiana Medical College in La Porte on Feb. 14, 1850. At this time, the school enrolled more than 100 students in each class and was so prominent that nearby Rush Medical College in Chicago proposed a merger to eliminate the competition. Indiana Medical College also had a microscope, imported from England, which stimulated young Mayo’s interest in microscopy. By contrast, Harvard College did not offer a microscope for medical studies until 1869. Indiana Medical College closed after Dr. W.W. Mayo’s graduation; its building and records were destroyed in a fire in 1856.

Dr. W.W. Mayo married Louise Wright in 1851. He continued his education in St. Louis, where the University of Missouri had a medical department at the time. Dr. Mayo received his second medical degree from the University of Missouri on Feb. 28, 1854. The university relocated its medical program to the city of Columbia in 1872 and the St. Louis-based program from which Dr. Mayo graduated became affiliated with Washington University in 1899. Unlike his diploma from Indiana Medical College, Dr. Mayo’s diploma from the University of Missouri survives in the care of the Mayo Historical Unit, third floor of the Plummer Building in Rochester.

With his wife’s support, Dr. Mayo inspired his sons, William James (1861-1939) and Charles Horace (1865-1939), with the spirit of scholarship. In 1883, Will earned his medical degree from the University of Michigan, which had recently instituted a three-year medical educational program. A family council determined it would be best for the younger brother to get a different viewpoint, so Charlie attended Northwestern University, graduating in 1888. The brothers’ diplomas also are preserved in the Mayo Historical Unit. Dr. Will and Dr. Charlie shared a lifelong love of learning. As Dr. Will said, “The glory of medicine is that it is constantly moving forward, that there is always more to learn.”

The diplomas of Dr. W.W. Mayo and his sons are among the oldest artifacts related to education at Mayo Clinic. As part of its mission to preserve and share Mayo Clinic history, with generous support from benefactors John and Lillian Mathews, the Mayo Historical Unit recently commissioned professional conservation of the diplomas at the Midwest Art Conservation Center in Minneapolis.

Watch this interview with Elizabeth Buschor, senior paper conservator, as she describes the restoration process, and an invitation from Mark Warner, M.D., Juanita Kious Waugh Executive Dean of Education, to visit the Mayo Historical Unit.

March

March 1914: "Mayo Clinic" becomes our official name

What’s in a name? A lot of impact … after all, independent research confirms that “Mayo Clinic” is among the best-known and most-trusted names in health care.

Medical historian W. Bruce Fye, M.D., shares the story.

“Mayo Clinic” was carved above the door of this building, which opened on March 6, 1914

Yet this powerful brand did not originate in a corporate business plan or finely tuned advertising campaign. Rather, “Mayo Clinic” is a grassroots title, whose evolution reflects the spirit of collaboration and service that is the hallmark of our organization.

In its early days, Mayo Clinic was a private medical practice – first, the solo practice of William Worrall Mayo, M.D., who began seeing patients in Rochester, Minn., in 1864. When his sons, William James and Charles Horace, graduated from medical school in the 1880s, they joined him, and the practice evolved into a family endeavor known informally as “The Doctors Mayo.”

Patient demand and the rise of specialization inspired the Mayo brothers to invite colleagues to join them in what was then a limited partnership. From the 1890s onward, the practice became known by the name of its partners, a formula that was increasingly cumbersome. Try saying “The Doctors Mayo, Stinchfield, Graham, Plummer, Judd and Balfour” when you answer the telephone.

At the same time, another name was gaining prominence. In contrast to many practitioners at the time, who jealously guarded their skills, the Mayo brothers had an open-door philosophy. They traveled widely to study best practices and warmly welcomed peers who wanted to learn from them. By the early 1900s, doctors from throughout the United States and around the world were coming to Rochester – the operating rooms were fitted out with observation galleries and mirrors on the ceiling to help them study surgical procedures.

Visiting doctors called these educational sessions “the Mayos’ clinic,” a name that resonated with patients, journalists and the railroads that printed schedules to Rochester. Variations of the title surfaced – “Mayo Brothers,” “The Mayo,” etc. – but “Mayo Clinic” had enduring appeal.

Even as patients and medical professionals flocked to Rochester, the Mayo brothers and their staff adapted a series of facilities in downtown Rochester to accommodate demand. By the second decade of the 20thcentury, the brothers decided it was time to design a building that was expressly tailored for their new concept of the integrated, multispecialty practice of medicine. When it opened on March 6, 1914, the name “Mayo Clinic” was carved in stone above the door. Since then, this name has continued to grow in stature and service to humanity.

April

April 1926: First issue of "Mayo Clinic Proceedings"

The commitment to share information in the medical literature runs deep at Mayo Clinic. In 1871 – when William James Mayo was ten years old and his brother, Charles Horace, was six – their father, William Worrall Mayo, M.D., published his first article in a medical journal.

The brothers continued this legacy as prolific medical authors.

In the early 1900s, as the practice expanded, the Mayos began wide-ranging initiatives to communicate with the medical profession. The establishment of a medical reference library and editing services for scholarly articles written by the staff, along with a photography studio and art studio to provide visual information, created an early mark of distinction for Mayo Clinic publications.

Maud Mellish Wilson

Maud Mellish (shown at right), who joined the Mayo practice in 1907 and later married Louis Wilson, M.D., was an early leader of many of these projects. In 1919, she began a daily publication for internal readership, The Clinic Bulletin, which included reports, lectures and items of interest from staff activities. In 1926, Mellish refocused the publication’s content on topics that were covered at the weekly staff meeting.

From its first issue on April 21, 1926, until Jan. 5, 1927, the publication went through four titles, settling at last upon Proceedings of the Staff Meetings of the Mayo Clinic. That name continued until 1964, when Mayo Clinic Proceedings was adopted to reflect the journal’s professional stature under the leadership of an editor-in-chief and editorial board.

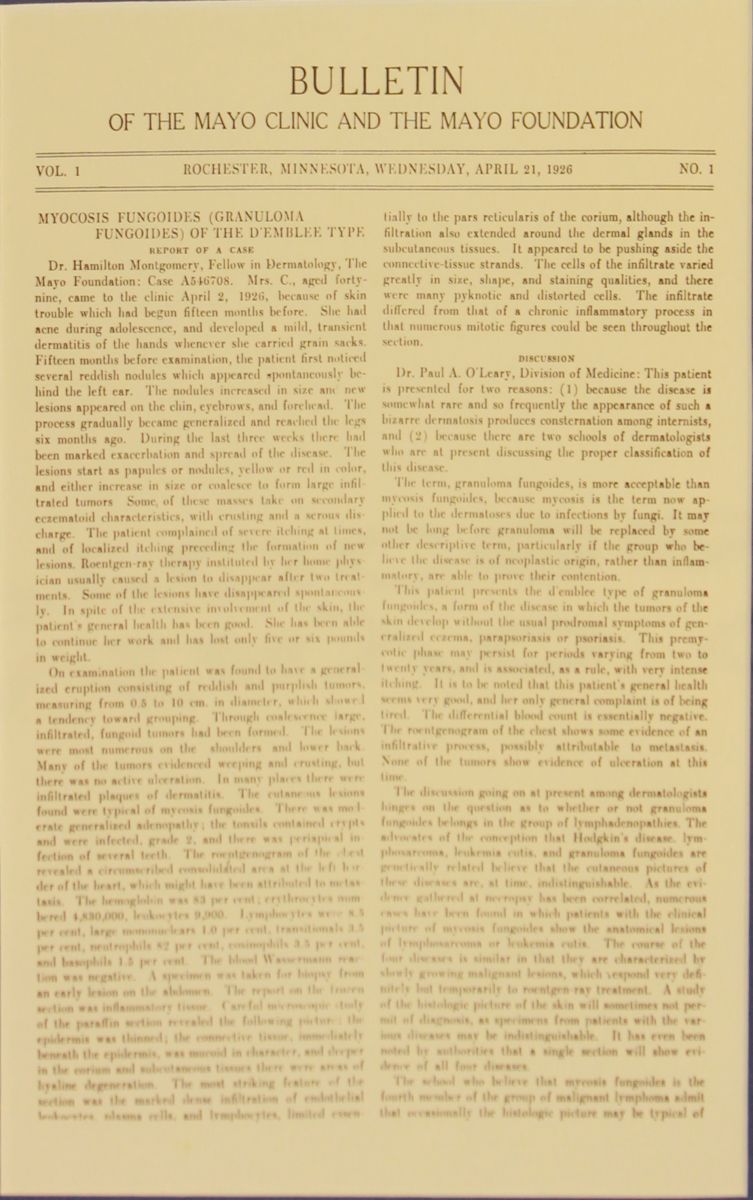

First issue of “Mayo Clinic Proceedings”

Eight physicians have served as editor-in-chief:

- Edwin D. Bayard, M.D. (1964-1970)

- Alvin B. Hayles, M.D. (1971-1976)

- John L. Juergens, M.D. (1977-1981)

- Robert G. Siekert, M.D. (1982-1986)

- Pasquale J. Palumbo, M.D. (1987-1993)

- Udaya B.S. Prakash, M.D. (1994-1998)

- William L. Lanier, M.D. (1999-2017)

- Karl A. Nath, M.D. (2017-present)

Throughout its history, many landmark articles have been published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings, documenting contributions to medicine by Mayo Clinic staff members as well as external colleagues. Today, with 125,000 readers, Mayo Clinic Proceedings is the world’s fourth-largest print circulation medical journal of any genre. Many more readers visit its web content each day at www.mayoclinicproceedings.org. The news media frequently report on medical advances and insights covered in the journal. Mayo Clinic Proceedings focuses on general and internal medicine, including articles and commentaries from leading specialists at Mayo Clinic and throughout the world.

Enjoy this commentary about “Mayo Clinic Proceedings” by former editor-in-chief William L. Lanier, M.D.

May

May 1940: Edith Mayo gives a nationwide radio address on Mother's Day

On Sunday, May 12, 1940, Americans awoke to a frightening new chapter in the spreading world war.

Two days earlier, the Germans had invaded Luxembourg, Belgium and Holland. Now they were surging toward Paris. In London, the appeasement-minded government of Neville Chamberlain collapsed, as the Nazi blitzkrieg routed Allied armies on the continent.

In the United States, strident voices – including Minnesota native Charles Lindbergh – declared that the unfolding disaster was none of America’s business, that there was no hope for the Western democracies.

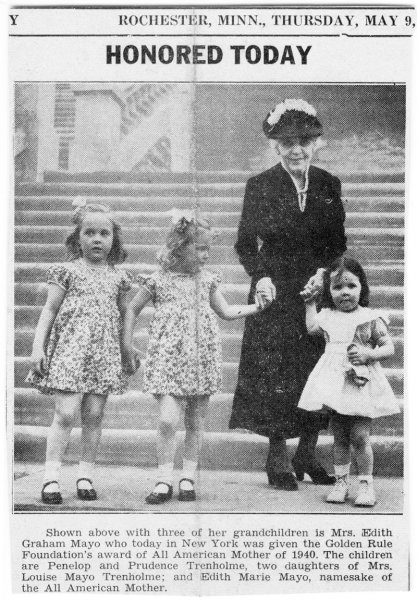

But May 12 was also Mother’s Day, and in New York City, a 73-year old widow, “a small, slender woman in a simple black dress, her silver hair parted softly above brown eyes,” walked toward a microphone at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. Edith Graham Mayo had been named American Mother of the Year by the Golden Rule Foundation, and she was using radio – the most powerful form of mass communication at the time – to reach a national audience.

Reflecting the importance of the occasion, she was introduced by Sara Delano Roosevelt, mother of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Amid the din of warmongers and defeatists, she spoke softly, turning attention away from herself and urging her listeners to reach out in humanitarian aid:

“… today there are untold myriads of mothers in Europe and Asia, as well as in impoverished homes of our own land, who are praying not for flowers but for flour, not for candies but for bread, not for greeting cards and telegrams but for medicine, sympathy and the necessities of life. If I know anything about the real heart of motherhood, I do not know of any way in which we could more appropriately honor our mothers than by doing for war orphans, widowed mothers and victims of military aggression in other lands, that which we would like to have done for our own if conditions were reversed … Let us all help in this great work.”

The patriotic, international and humanitarian values that Edith Mayo – “Mrs. Charlie” – expressed were emblematic of Mayo Clinic. They would undergo stern trials in the years to come.

In 1940, Mayo Clinic was in transition, having survived the Great Depression and the deaths of many of its founders and pioneers – both Mayo brothers, Sister Joseph Dempsey, Dr. Henry Plummer and Maud Mellish Wilson, among others. A new generation was assuming leadership, even as the most violent war in history was beginning.

“The greatest generation” is a phrase used by award-winning journalist Tom Brokaw, a member of the Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees, and that description certainly applies to the men and women of Mayo Clinic during World War II. They served in all branches of the military, in both the Atlantic and Pacific theaters of war. On the Home Front, the diminished staff provided care to record numbers of patients, while conducting top-secret aero-medical research that helped win the war and launch post-war jet aviation and the space program.

In her calm, caring way, Mrs. Charlie helped Mayo Clinic and the nation prepare to meet unparalleled challenges with strength and purpose. Indeed, the years of Mayo’s greatest expansion were yet to come.

June

June 1939: Lou Gehrig comes to Mayo Clinic

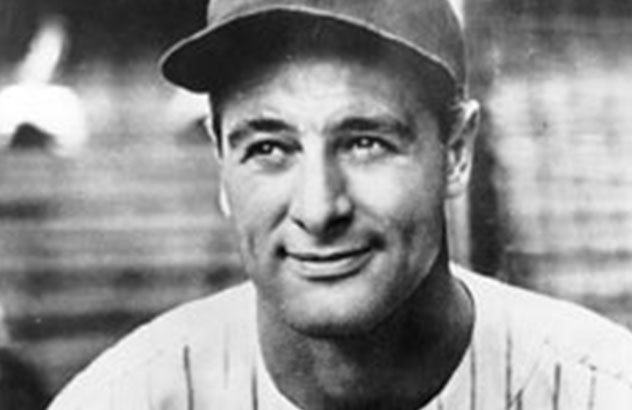

They called him the Iron Horse …the Pride of the Yankees in their golden years. But when baseball great Lou Gehrig came to Mayo Clinic in 1939, he gave his name to an illness called amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Since then, around the world, ALS has been known as “Lou Gehrig’s disease.” Today, Mayo Clinic is on the forefront of innovative research to advance medical understanding of the condition.

A native of New York City, Gehrig signed with the Yankees in 1923 and set several major league records in his career including most grand slam home runs and the milestone for which he is most remembered, the longest streak of consecutive play – 2,130 games – which stood until 1995. Gehrig’s diagnosis cut short that remarkable career. Due to his prominence, Mayo Clinic took what then was a virtually unheard-of step and issued a public announcement:

To whom it may concern:

This is to certify that Mr. Lou Gehrig has been under examination at the Mayo Clinic from June 13 to June 19, 1939, inclusive.

After a careful and complete examination, it was found that he is suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. This type of illness involves the motor pathways and cells of the central nervous system …

The nature of this trouble makes it such that Mr. Gehrig will be unable to continue his active participation as a baseball player, inasmuch as it is advisable that he conserve his muscular energy…

Gehrig found comfort in the care that Mayo Clinic provided during the course of several medical visits that summer. The staff of the Kahler Hotel baked a cake for his 36th birthday on June 19. He attended ball games and conducted baseball clinics and demonstrations for local youth teams. (Photo at left courtesy of History Center of Olmsted County.) He befriended many people at Mayo, especially Paul O’Leary, M.D., who became a close and highly respected friend for the rest of Gehrig’s life. In his biography Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig (Simon & Schuster, 2005), Jonathan Eig wrote:

Gehrig wrapped himself in the blanket of Rochester’s innocent charm. Away from the big-city reporters and expectant teammates, away from his anxious wife and parents, he unwound completely. … As he grew accustomed to the fact that he would never play again for the Yankees, Gehrig began to treat the Mayo Clinic as if it were his new team. He wrote letters to his doctors in Rochester, thanking them for their time and attention, and vowing to follow their advice throughout his treatment. Over and over, he expressed his gratitude. …he appreciated the personal attention he’d received in Rochester – from doctors, from hotel workers, from neighborhood kids, even from the local press. Gehrig had never been so coddled and so warmly embraced in all his life as he had been during his week of exams at the clinic.

Soon after Gehrig’s diagnosis, on July 4, 1939, the Yankees hosted Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day, and he gave one of the most revered speeches in sports history, saying in part, “Today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth. …I may have had a bad break, but I have an awful lot to live for.”

June 1987: Mayo Clinic opens in Arizona

From the mountain lion they saw roaming Mayo’s new property in Scottsdale to the time the soles of his tennis shoes melted on the hot asphalt of Phoenix, Dr. Richard Hill and his wife, Barbara, had many occasions to paraphrase Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz: “We’re not in Minnesota anymore!”

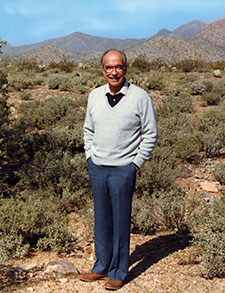

Dr. Richard Hill on the site of Mayo’s campus in Scottsdale, Arizona, circa 1985

As Mayo Clinic established itself in the southwest, Dr. Hill served as the first chief executive of Mayo’s practice in Arizona from 1987 to 1992. Mrs. Hill worked tirelessly and creatively to nurture a sense of community among the pioneering colleagues and their families who ventured to the new location.

Every Mayo Clinic location has its own story. In Rochester, Minn., the clinic evolved from the Mayo family’s medical practice. Expansion to Jacksonville, Fla., came largely at the behest of the Davis family. After extensive study, Mayo’s leaders proactively identified Arizona as a place where its unique model of care could bring added value to a strong, vibrant community and region. Mayo’s outreach to Arizona drew upon deep roots. In the 1930s, both Mayo brothers had retirement homes in Tucson, reflecting their love of the region. That tradition had added resonance by the 1980s, as Mayo Clinic looked for a geographic balance to its locations in the Midwest and Southeast.

“From the start, we determined that Arizona would not be a ‘satellite’ location,” recalls Dr. Hill. “We planned a full Mayo Clinic presence of patient care, research and education.” There were adjustments, however. Zoning regulations presented requirements that no one ever had to deal with in Minnesota: the need to keep buildings below a certain level to preserve lines of sight toward nearby mountains, and the use of specific colors of stone and paint to harmonize with the desert environment.

On June 29, 1987 – the 126th anniversary of Dr. Will’s birth – Mayo Clinic opened in Scottsdale. Forty-six physicians and about 220 allied health colleagues were on hand to serve more than 1,800 people who had made appointments even before the first day. The number of staff – and patients –rose steadily. Phase II construction began three years ahead of schedule.

As in Florida, after the early years of working closely with a community-based hospital, the time came for Mayo Clinic to design and construct its own hospital. In this case, the decision led to developing a second campus in Phoenix. Mayo Clinic Hospital opened on September 12, 1998. Barbara Bush, former First Lady and a member of the Board of Trustees, was keynote speaker. Her words express the dedication that inspires the work of Mayo’s team in Arizona:

“Perhaps no other facility is the scene of so many profound human emotions and experiences – life and death, fear, hope and joy. We can be confident that it will be a place of caring in the fullest sense of the word. To me, the hallmark of Mayo is medical excellence and human kindness.”

July

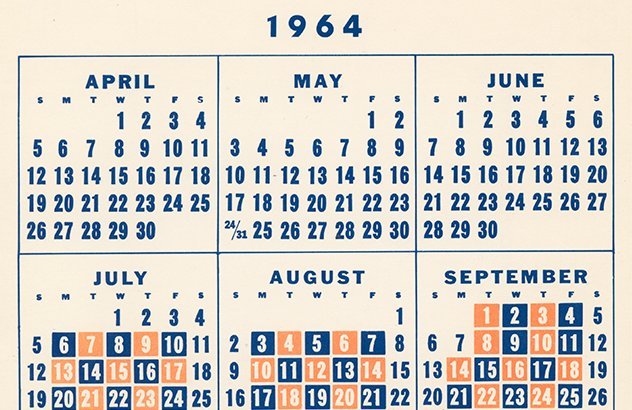

July 1964: The orange and blue calendar becomes official

QUESTION: How do dairy companies and the University of Illinois have a daily impact at Mayo Clinic?

ANSWER: In the ubiquitous orange and blue calendar, which chronicles activities throughout the institution.

For patients and employees alike, it’s common to hear that a surgeon operates on “orange days” or that a committee meets on the “second blue Tuesday” of each month. The story behind this designation provides a unique perspective on the Mayo Clinic decision-making process.

In its earliest days, Mayo Clinic was open seven days a week, since many patients were farm families, who only came to Rochester on the weekend. By the mid-20th century, however, Mayo was open Monday-Friday and a half-day on Saturday.

Administrator Richard Cleeremans wrote a description that is on file in the Mayo Clinic Historical Unit: “Saturday was a fully scheduled surgical day resulting in what actually was a six-day surgical week. This made it convenient to divide the surgeons’ week into an equal number of surgical and consulting days. Surgeons who operated on Monday, Wednesday and Friday consulted in the Clinic on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday. The reverse schedule was in effect for surgeons who operated on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday.”

Changing social patterns and new labor laws led Mayo Clinic to switch to a five-day work week starting in July 1964. It became crucial to identify which days, on a rotating rather than a fixed basis, surgeons would be in the operating room and the consulting office.

This was the era when milk was delivered to homes on alternating days. Dairy companies provided a two-color calendar to let customers know which days they would receive milk. Here was a readily understood and accepted prototype that Mayo could follow.

This was the era when milk was delivered to homes on alternating days. Dairy companies provided a two-color calendar to let customers know which days they would receive milk. Here was a readily understood and accepted prototype that Mayo could follow.

The colors to use on the calendar, however, proved to be a contentious issue. In fact, there was gridlock – many suggestions, but no agreement.

The issue worked its way through the committee system and up to the Board of Governors, then chaired by L. Emmerson Ward, M.D. (pictured below.) With tongue firmly in cheek – and other pressing matters on the agenda, Cleeremans described how Dr. Ward “acknowledged that it certainly was appropriate that a decision of this magnitude be resolved by the Clinic’s governing board.”

(pictured below.) With tongue firmly in cheek – and other pressing matters on the agenda, Cleeremans described how Dr. Ward “acknowledged that it certainly was appropriate that a decision of this magnitude be resolved by the Clinic’s governing board.”

To resolve the dispute, Dr. Ward surveyed the room and said, “I have always favored the colors of my alma mater, the University of Illinois. Unless there are objections, I propose orange and blue for the colors of the new surgical calendar.”

Motion passed – and sustained for half a century of wide-ranging growth and expansion at Mayo Clinic. Today, from websites to wallet cards, orange and blue define Mayo’s activities. As Richard Cleeremans noted, “It’s interesting to speculate on what colors may have been used if Dr. Ward had attended another university.”

August

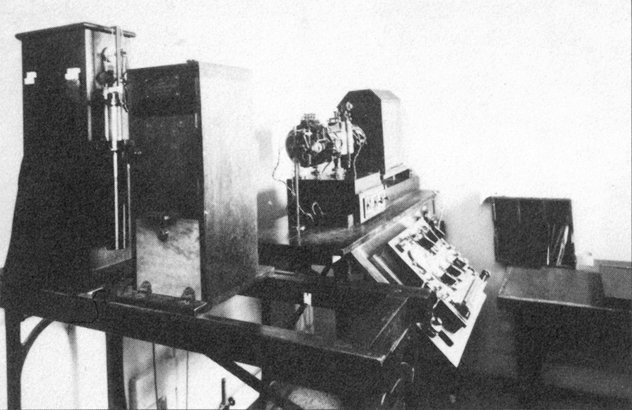

August 1914: The first electrocardiogram at Mayo Clinic

August 1914 brought the unfolding tragedy of World War I. “The lamps are going out all over Europe,” said the British Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey. “We shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.”

Invented by Dutch physiologist Willem Einthoven in 1902, the electrocardiograph provided a reading of the heart’s electrical pattern, which remains a mainstay of cardiovascular diagnosis today. But diffusion of the new technology – costly and cumbersome – was slow. Many of the first devices were used for animal research rather than patient care. As late as 1913, there was only one electrocardiograph in Minnesota, at Elliott Memorial Hospital, Minneapolis.

By that time, however, construction was under way for the Mayo Clinic building in Rochester – the first facility in the world designed for the integrated, multispecialty group practice of medicine. Henry Plummer, M.D., designer of the building and developer of the philosophy it represented, included space for an electrocardiograph.

Mayo Clinic ordered its apparatus from the Cambridge Scientific Instrument Company in England. The device arrived soon after the building opened, and Mayo Clinic recorded its first electrocardiogram on August 1, 1914 – fortuitous timing, since naval blockade and submarine warfare soon drastically curtailed travel to and from Europe.

Mayo Clinic ordered its apparatus from the Cambridge Scientific Instrument Company in England. The device arrived soon after the building opened, and Mayo Clinic recorded its first electrocardiogram on August 1, 1914 – fortuitous timing, since naval blockade and submarine warfare soon drastically curtailed travel to and from Europe.

Dr. Plummer was one of the first American physicians to recognize the electrocardiograph’s value. Use of the technology helped Mayo Clinic expand from a nearly exclusive focus on surgery to develop complementary priorities in diagnosis and non-operative treatment for a wide range of conditions.

Cardiology was one of several disciplines that became recognized as a specialty in the World War I era, with Mayo Clinic achieving early and sustained leadership.

Fredrick Willius, M.D. (shown at right), a pioneering academic cardiologist who began recording and interpreting electrocardiograms at Mayo Clinic in 1916, explained:

The patient is first received by one of the examining physicians, who is a graduate student in the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. He records the patient’s history, makes a complete physical examination, and writes a tentative diagnosis and opinion. The patient is then seen by the head of the section or by his associate or first assistant, who indicates the special investigations that are to be undertaken. On completion of the special examinations the patient is seen by the head of the section or his associate, who carefully reviews the history and the records of the physical examination, and correlates laboratory records and other data. A diagnosis is made and the treatment outlined.

Written in 1927, this description remains true of Mayo’s thorough approach and integration of clinical care, education and research in service to patients.

With appreciation to W. Bruce Fye, M.D., whose book, Caring for the Heart: Mayo Clinic and the Rise of Specialization, will be published by Oxford University Press in 2015.

September

September 1889: St. Mary's Hospital opens; nurse anesthesia program begins

St. Mary’s Hospital opened on Sept. 30, 1889, with 27 beds and, according to a newspaper report of the time, “every feature designed to make it pleasant and homelike for the sick.”

Although the hospital’s name and spelling have evolved – to Saint Marys Hospital and, today, the Saint Marys Campus of Mayo Clinic Hospital-Rochester – the anniversary of this event includes milestones of enduring significance:

Franciscan-Mayo Collaboration – St. Mary’s was founded by the Sisters of St. Francis, whose collaboration with Dr. William Worrall Mayo and his sons, William James (Dr. Will) and Charles Horace (Dr. Charlie), began when a tornado struck Rochester, Minn., in 1883. The opening of St. Mary’s brought the Roman Catholic Sisters into daily contact with the Protestant Mayos and their associates, who came from diverse walks of life, establishing a culture of mutual respect that defines Mayo Clinic today.

National and Global Renown – Several factors, which parallel Mayo’s current activities, propelled St. Mary’s Hospital and the Mayo practice into early prominence. Highly innovative, St. Mary’s was among the first hospitals to embrace the new “germ theory” of aseptic surgery … the team approach to patient care resulted in remarkable survival rates … city amenities and advances in transportation attracted increasing numbers of patients … the news media reported on the “clinic in the cornfield”… the Mayo brothers served as leaders of many professional organizations and had an “open door” philosophy of welcoming colleagues to exchange information.

National and Global Renown – Several factors, which parallel Mayo’s current activities, propelled St. Mary’s Hospital and the Mayo practice into early prominence. Highly innovative, St. Mary’s was among the first hospitals to embrace the new “germ theory” of aseptic surgery … the team approach to patient care resulted in remarkable survival rates … city amenities and advances in transportation attracted increasing numbers of patients … the news media reported on the “clinic in the cornfield”… the Mayo brothers served as leaders of many professional organizations and had an “open door” philosophy of welcoming colleagues to exchange information.

The Profession of Nurse Anesthesia – Innovation and teamwork led to the development of medical specialties. One of the first new disciplines was nurse anesthesia.

One of the first new disciplines was nurse anesthesia.

Upon completing her studies in Chicago, Edith Graham, R.N. (right), returned to her home town in 1889 as the first professionally educated nurse in Rochester. She taught the Sisters of St. Francis, who were schoolteachers, in the principles of nursing and began the Mayo tradition of excellence in nurse anesthesia education. With her dedication to patients and technical skills, Edith Graham was a natural for this role, using the amber-colored ether bottle pictured above, until her marriage to Dr. Charlie in 1893.

The second nurse anesthetist was Alice Magaw, R.N., who made so many contributions that the Mayo brothers called her “The Mother of Anesthesia,” an accolade that remains in the professional literature today. In 1906, she reported on 14,000 cases without one death attributable to anesthesia. That same year, a German surgeon described the phenomenon of anesthetists from the world’s leading medical centers coming to Rochester to learn from highly skilled nurses.

Today, the Nurse Anesthesia Program is internationally recognized for excellence, with practitioners at each Mayo Clinic hospital as well as alumni who work at many other institutions. In 2014, exactly 125 years after Edith Graham, R.N., began teaching the Sisters of St. Francis, Mayo Clinic inaugurated a 42-month doctoral-level nurse anesthesia program (Doctor of Nurse Anesthesia Practice – DNAP), upholding the highest professional standards in service to patients.

September 1964: Mayo Centennial

In 1964, Mayo Clinic celebrated its centennial with a variety of scholarly activities.

The Mayo Centennial Seal

The U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp honoring the Mayo Brothers in September 1964

October

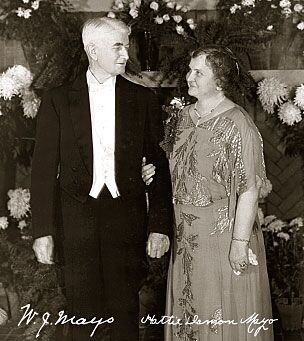

October 1919: Deed of Gift

Like many entrepreneurs, the Mayo brothers faced a major decision: Looking beyond their lifetimes, they wondered what would happen to the organization they established. In essence, they decided the best way to secure the future of Mayo Clinic was to give it away.

Therefore, in the years surrounding World War I, they undertook a series of steps that transformed their private medical partnership into a not-for-profit organization with a salaried staff.

The culminating point came with the signing of a Deed of Gift on Oct. 8, 1919. Significantly, not only did Dr. Will and Dr. Charlie sign the deed, but so did their wives, Hattie Damon Mayo and Edith Graham Mayo. In every respect, this was a joint decision. The Deed of Gift transferred all assets of Mayo Clinic and the majority of the two families’ life savings into a not-for-profit organization. At the time, this gift was valued at more than $10 million; today, the Mayos’ gift would be worth more than $100 million.

The culminating point came with the signing of a Deed of Gift on Oct. 8, 1919. Significantly, not only did Dr. Will and Dr. Charlie sign the deed, but so did their wives, Hattie Damon Mayo and Edith Graham Mayo. In every respect, this was a joint decision. The Deed of Gift transferred all assets of Mayo Clinic and the majority of the two families’ life savings into a not-for-profit organization. At the time, this gift was valued at more than $10 million; today, the Mayos’ gift would be worth more than $100 million.

This was an act without precedent in American medicine. It secured the future of Mayo Clinic in its mission of excellence in patient care, research and education, and inspired future generations of patients and staff to continue the tradition of generosity.

This was an act without precedent in American medicine. It secured the future of Mayo Clinic in its mission of excellence in patient care, research and education, and inspired future generations of patients and staff to continue the tradition of generosity.

Far more than a legal document, the Deed of Gift was a statement of the founders’ philosophy. Its principles continue to guide Mayo Clinic today:

“… the success of the Clinic, past, present and future, must be measured largely by its contributions to the general good of humanity.”

October 1986: Mayo Clinic opens in Jacksonville, Florida

“Looks to me like we are pretty far out in the woods,” said Paul Volcker, chairman of the Federal Reserve and a member of the Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees. His comment drew a ripple of laughter, but even then there was sense of hope and confidence in the future.

The occasion was the groundbreaking for Mayo’s new venture in Jacksonville, Fla. – also its first expansion outside of Minnesota. The story of how a Midwestern “clinic in the cornfield” took root in the Sunshine State, opening on Oct. 13, 1986, was a leap of faith comparable to other key events in Mayo’s history.

From its earliest days, Mayo Clinic had connections to Florida. In the 1890s, when railroads first brought tourists to Florida, Dr. William Worrall Mayo enjoyed spending time in St. Augustine, near Jacksonville. His eldest son, Dr. Will, who usually combined professional and avocational interests on his travels, visited Florida often. Dr. Will’s boat, the North Star, docked at Jacksonville on a 2,500-mile trip across the Gulf of Mexico and up the Atlantic coast of Florida in 1925.

Mayo Clinic also drew patients from Florida. Among them were members of the Davis family of Jacksonville, founders of the Winn-Dixie grocery store chain. James Elsworth (J.E.) Davis and his brothers, with their families, began coming to Mayo Clinic in 1948. The brothers’ commitment to seeking excellent medical care was inspired in part by the premature death of their father in 1934 due to a misdiagnosed condition.

J.E. Davis developed close friendships with Dr. Hugh Butt and many of his colleagues on the Mayo Clinic staff. During a telephone call on a winter morning in 1978, Dr. Butt mentioned that he almost suffered frostbite walking to work in minus-30 degree temperatures. Mr. Davis replied that Mayo should consider expanding into the Sunbelt.

From this conversation, an action plan developed, with the Davis family taking the lead in offering philanthropic support and entrée to the community. Many factors augured that the timing was right – among them, the U.S. population was trending to the south and new technology facilitated communication between remote locations. The concept of opening in Florida worked its way through the Mayo system of committees and boards, but at the point of decision, Mayo Clinic respectfully declined. Persistent in his vision, loyalty and generosity, J.E. Davis wrote to Mayo’s senior leadership, explaining that he understood challenges from his own business experience: “Those who survive will very likely be those who recognize the need for change and are willing to take action and risk.”

Conversations resumed, and the Davis family stepped forward with an additional gift of land and other support, including a community-based fundraising drive, to help Mayo build and support the new facility. After further analysis, Mayo gratefully accepted. Amid gathering momentum, a vision for Mayo Clinic in Florida evolved. It would not be a “satellite,” but rather a full-fledged Mayo presence with the three-shield focus on patient care, education and research.

Even before it opened, more than 2,700 patients from 30 states and six countries had made appointments. Notable developments on the campus include the opening of a hospital adjoining the outpatient practice in 2008. The founders’ vision continues today, as the Florida campus plays a key role in Mayo Clinic’s mission of serving humanity and advancing medical science.

November

November 1920: Politics and the Mayo brothers

The election cycle is a reminder that the Mayo brothers were approached to run for office. They respectfully declined, but encouraged citizens to vote and be active in the political process.

Four years later, a movement began to draft Dr. Charlie to run for President of the United States. He received numerous letters of support from patients and physicians, and even from the governors of several states. National media including The New York Times covered the story. When Dr. Charlie was the guest speaker at a medical meeting, the host who was introducing him picked up on this theme, imploring Dr. Charlie to use “surgical precision” to “cut out the corruption in Washington.” Dr. Charlie, who had a quick wit but no intention of running for office, replied that he would appoint his host – a well-known internist – as “Secretary of the Interior.”

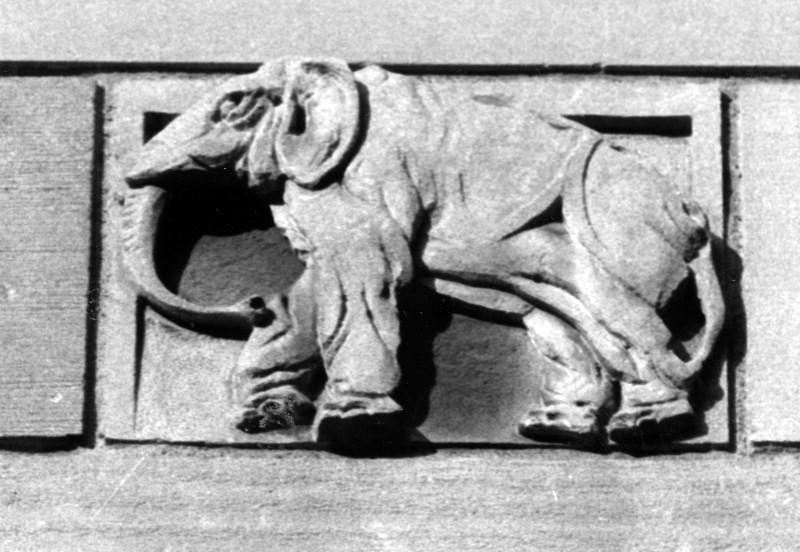

Political symbols adorn the Plummer Building on the Rochester campus. The building opened during the presidential campaign of 1928. Henry Plummer, M.D., supported the Republican candidate, Herbert Hoover, while his friend, Jacob Raskob, who served as the national Democratic campaign manager, backed Al Smith. The two men enjoyed bantering about their respective candidates. With Dr. Plummer’s approval, two decorative stones were added to the new building’s exterior, depicting the outcome of this particular election: a triumphant elephant and a dejected donkey.

Four years later, a movement began to draft Dr. Charlie to run for President of the United States. He received numerous letters of support from patients and physicians, and even from the governors of several states. National media including The New York Times covered the story. When Dr. Charlie was the guest speaker at a medical meeting, the host who was introducing him picked up on this theme, imploring Dr. Charlie to use “surgical precision” to “cut out the corruption in Washington.” Dr. Charlie, who had a quick wit but no intention of running for office, replied that he would appoint his host – a well-known internist – as “Secretary of the Interior.”

Political symbols adorn the Plummer Building on the Rochester campus. The building opened during the presidential campaign of 1928. Henry Plummer, M.D., supported the Republican candidate, Herbert Hoover, while his friend, Jacob Raskob, who served as the national Democratic campaign manager, backed Al Smith. The two men enjoyed bantering about their respective candidates. With Dr. Plummer’s approval, two decorative stones were added to the new building’s exterior, depicting the outcome of this particular election: a triumphant elephant and a dejected donkey.

To see these images, stand behind the bus shelter on Second Street SW (across the street is another bus shelter, surface parking lot and the Franklin Heating Station). Look up between the lowest-level window and the second-lowest window.

To see these images, stand behind the bus shelter on Second Street SW (across the street is another bus shelter, surface parking lot and the Franklin Heating Station). Look up between the lowest-level window and the second-lowest window.

November 1921: Dr. Charlie commissioned as brigadier general in the United States Army

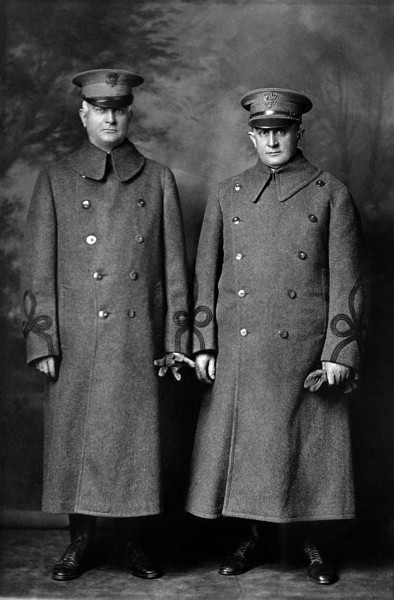

On Nov. 4, 1921, Charles H. Mayo, M.D., was commissioned as a brigadier general in the Medical Reserve Corps of the United States Army. This recognition was followed by a similar commission for his brother, William J. Mayo, M.D, on Dec. 23 that year.

The Mayo brothers combined global values and American patriotism. Dr. Will joined the Medical Reserves Corps in 1912, followed by Dr. Charlie the next year. Like many Americans, they watched the outbreak of hostilities in Europe in 1914 with growing anticipation that the United States would become involved in the conflict. Both brothers served on the General Medical Board of the United States Council for National Defense shortly after it was established in 1916 with the goal of preparing America for possible military action.

Dr. William J. Mayo M.D. (left) and Dr. Charles H. Mayo, M.D.

When the United States declared war on Imperial Germany in April 1917, the Surgeon General of the U.S. Army, William Gorgas, M.D., asked Dr. Will to be a consultant to his office in Washington, D.C. Under Dr. Will’s leadership, a team of surgical specialists was formed, on which Dr. Charlie also served.

As with their personal and professional travel, the brothers alternated trips to the nation’s capital, so one was always at the Clinic in Rochester. Unfortunately, the demands of wartime service in addition to pressing patient loads at the Clinic took a toll on the middle-aged brothers. On one of his trips to Washington, Dr. Charlie came down with pneumonia. Dr. Will developed a severe case of jaundice that kept him away from the Clinic for two months. Both brothers recovered, however, and had many subsequent years of professional activity.

In 1926, the Mayo brothers were honored for their service to the nation when they received the Distinguished Service Medal of the United States.

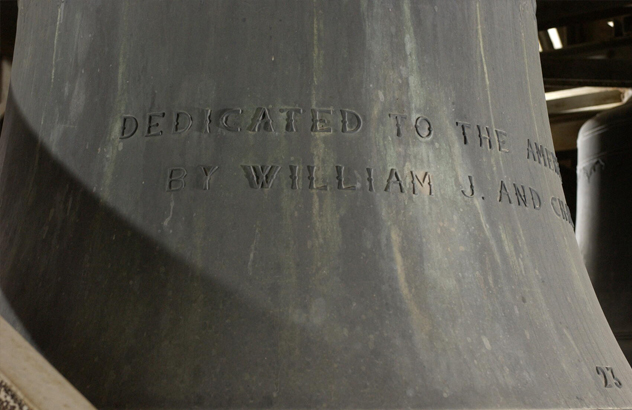

The Mayo brothers had the highest regard for service members in the American military.  In 1928, they donated 23 bells for the Rochester Carillon at the top of the new diagnostic building, later named the Plummer Building. The largest bell bears the inscription “To the American Soldier,” any by tradition every concert of the Rochester Carillon begins with “My Country Tis of Thee.”

In 1928, they donated 23 bells for the Rochester Carillon at the top of the new diagnostic building, later named the Plummer Building. The largest bell bears the inscription “To the American Soldier,” any by tradition every concert of the Rochester Carillon begins with “My Country Tis of Thee.”

During the dedication ceremony, Dr. Will said:

“Today, we dedicate this carillon to the American soldier, in grateful memory of heroic actions on land and sea to which America owes her liberty, peace and prosperity.”

December

December 1941: Pearl Harbor and Mayo Clinic

December 7, 1941, was “a date which will live in infamy,” in the words of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and drew the United States into a global conflict that had been escalating for several years.

Pearl Harbor connects the stories of two Mayo Clinic nurses. Their experiences could not have been more different – yet both demonstrate Mayo’s values in action.

Ruth Erickson, R.N.

After graduating from the Kahler Hospital’s School of Nursing, Ruth Erickson, R.N., joined the Navy Nurse Corps in 1936. In April 1940, she was assigned to the naval hospital at Pearl Harbor, where she enjoyed island life and developed leadership skills.

Sunday, December 7, was her day off, but that morning she decided to visit her friends who were on duty. She was at the hospital, talking over coffee, when the bombs started falling. Ships exploded in the harbor as thick, burning oil flowed across the water. She later recalled:

My heart was racing, the telephone was ringing … Smoke was rising from the burning ships … I ran to the orthopedic dressing room … drew water into every container … and set up the instrument boiler … The first patient came at 8:25 a.m. with a large opening in his abdomen and bleeding profusely … Then the burned patients streamed in … There was heavy oil on the water and the men had dived off the ship and swum through it to Hospital Point … We gave those grievously injured patients sedatives for their intense pain.’

The surprise attack claimed nearly 3,600 dead and wounded military personnel and civilians. Within 24 hours, Japanese forces launched wide-ranging assaults throughout the Pacific.

Erickson and her colleagues worked round the clock, throughout the attack and for more than a week that followed, caring for the critically injured survivors. Ten days later, she was ordered to accompany patients who were being evacuated to the mainland for further care. Erickson ultimately earned the rank of captain and served with distinction as director of the United States Navy Nurse Corps. As a hands-on practitioner as well as a military executive, she placed the needs of each patient first.

For Teruko Yamashita, Pearl Harbor was devastating in a different way. Her family, along with approximately 120,000 Japanese-Americans living on the United States west coast, was uprooted and moved to detention camps under armed guard.

Teruko Yamashita

Yet the war also opened opportunities for Yamashita and other Japanese-Americans. They were able to leave the camps as part of an educational initiative that helped advance desegregation and other social changes. To meet the need for nurses, Congress passed the Nurse Training Act in 1943, stipulating that there “shall be no discrimination …

on account of race, creed or color.”

Sister Antonia Rostomily, director of Saint Marys School of Nursing, was “a formidable teacher and disciplinarian,” but also “a woman of good heart and common sense.” She knew that many schools would not accept Japanese-American students but believed that Saint Marys Hospital, with its experience serving international patients, would be a desirable setting. Under her leadership, the school admitted Japanese-American nursing students and hired Japanese-American nurses for diverse leadership positions – a practical measure to address staff shortages and a symbolic message of tolerance amid the pressures of wartime. Years later, after retiring from her successful nursing career, Yamashita recalled with gratitude:

For three years, I had lived with my family of seven members in one little room in a city of barracks. Leaving for the outside world, alone, was a little frightening. Arriving in Rochester, I was overwhelmed … The standard of education was the highest, the instructors were excellent, and the medical care, the finest!

Tom Brokaw, member of the Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees and award-winning author, used the phrase “Greatest Generation” to describe Americans who met the demands of World War II. That phrase is certainly appropriate for Ruth Erickson, Teruko Yamashita and Sister Antonia, each of whom served humanity with distinction, in combat and on the Home Front.

For More Information:

The Nurses of Mayo Clinic: Caring Healers. By Arlene Keeling, R.N., Ph.D., F.A.A.N.

The Sisters’ Story: Saint Marys Hospital. Two volumes by Sister Ellen Whelan, Ph.D.

December 1950: Mayo Clinic “Cosmorama” production

The yuletide season is traditionally a time of social occasions and get-togethers with family, friends and co-workers. This has also been true throughout much of Mayo Clinic’s history.

After the first Mayo Clinic building opened in 1914, the lobby was used for holiday entertainment. It is difficult to document all the gatherings, but between 1920 and 1925, they were held annually. An announcement dated Dec. 21, 1921, for example, proclaimed that “Father Christmas” would attend the celebration. By the mid-1920s, the focus shifted to smaller, sectional gatherings.

In 1932, Boyd Gardner, D.D.S., head of the Dental Section, suggested that an all-staff gathering would lift spirits during the grim years of the Great Depression. His idea led to a three-year period of events that featured local entertainment. The 1934 gala was a spoof of a professional meeting entitled the “75th Annual Convention of the Kombined Kick-A-Poo Kounty Medical Association,” followed by dancing in the lobby.

Duke Ellington

All-staff parties were discontinued in the mid-1930s but revived with the opening of Mayo Auditorium, now known as Mayo Civic Center. These events featured nationally known orchestras of the Big Band era: Duke Ellington (1939) (shown below on left), Ray Noble (1940) and Russ Morgan (1941). With America’s entry into World War II, parties were suspended from 1942 to 1944; instead, Mayo Clinic donated funds to the USO and the war effort.

After the war, all-staff parties and headline entertainment returned with Chuck Foster’s band (1945), followed by Charlie Spivak (1946), Wayne King (1947), Griff Williams (1948), Lawrence Welk (1949) (shown below on right), Frankie Carle (1950), Lou Breese (1951), Jan Garber (1952) and, finally, Tony Pastor (1953).

Lawrence Welk

Mayo Clinic staff members added their own skills to these events with productions such as the “Folly of 1949” and the “Cosmorama of 1950.” These productions ran up to three hours, followed by a dance. As many as 200 staff members were involved in the productions, which were performed over two nights to accommodate Mayo Clinic staff and guests.

The growth of Mayo Clinic made it too demanding to support the logistics of an all-staff event after 1953 and the institution moved away from highlighting any one particular holiday. The spirit of fellowship and camaraderie from the all-staff Christmas parties continues to thrive in contemporary events, however, such as Mayo’s Got Talent, the Festival of Cultures and Heritage Days. Many colleagues, departments and work groups continue to plan social activities at this time of year.

The Mayo Clinic Archive contains a film of the “Cosmorama of 1950.” Watch the video below for scenes from the staff talent review in that large-scale production. (Video also shown above.) In 1950, the Mayo Building was in an early stage of construction. Note how the master of ceremonies, Edward Rynearson, M.D., described “the hole in the ground” located “to the west of the Clinic” as the latest expression of the vision of the Mayo brothers.

Acknowledgments: Clark W. Nelson, Mayo Roots: Profiling the Origins of Mayo Clinic, pages 156-157.

Terms of Use and Information Applicable to this Site

Copyright © 2001-2013 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. All Rights Reserved.