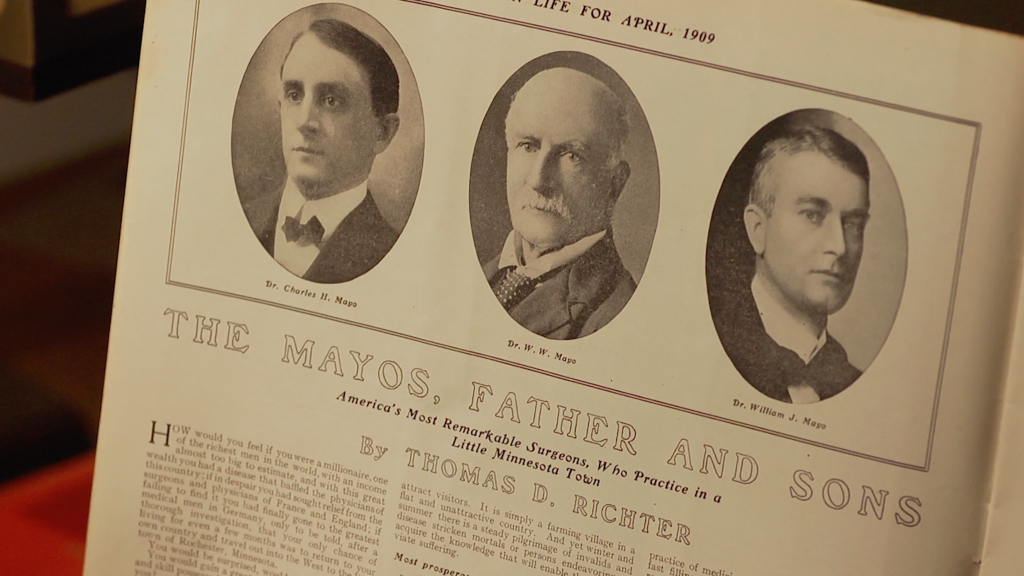

Two small-town doctors develop a new model of healthcare and build a world-renowned clinic based on the value, “the needs of the patient come first.”

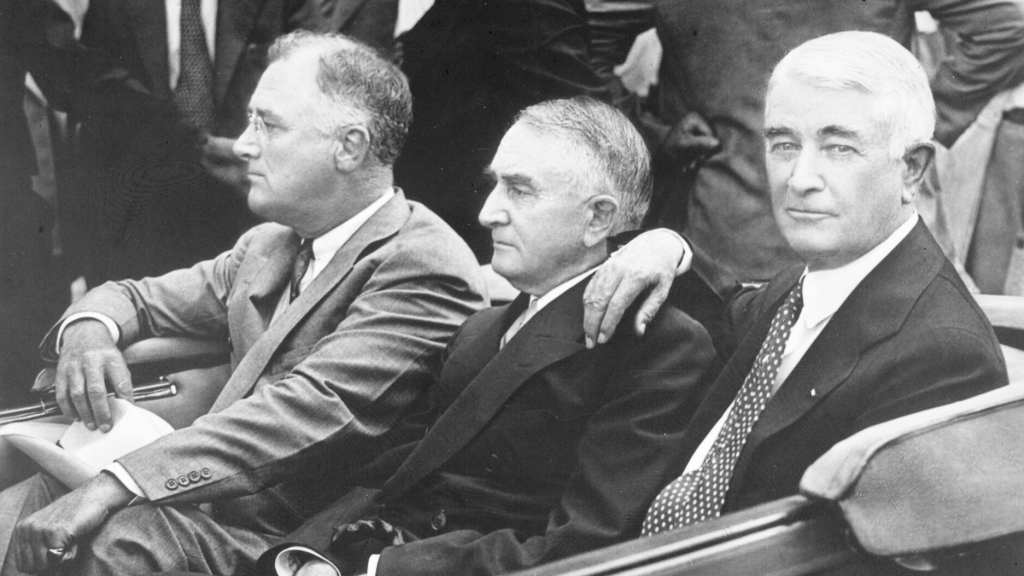

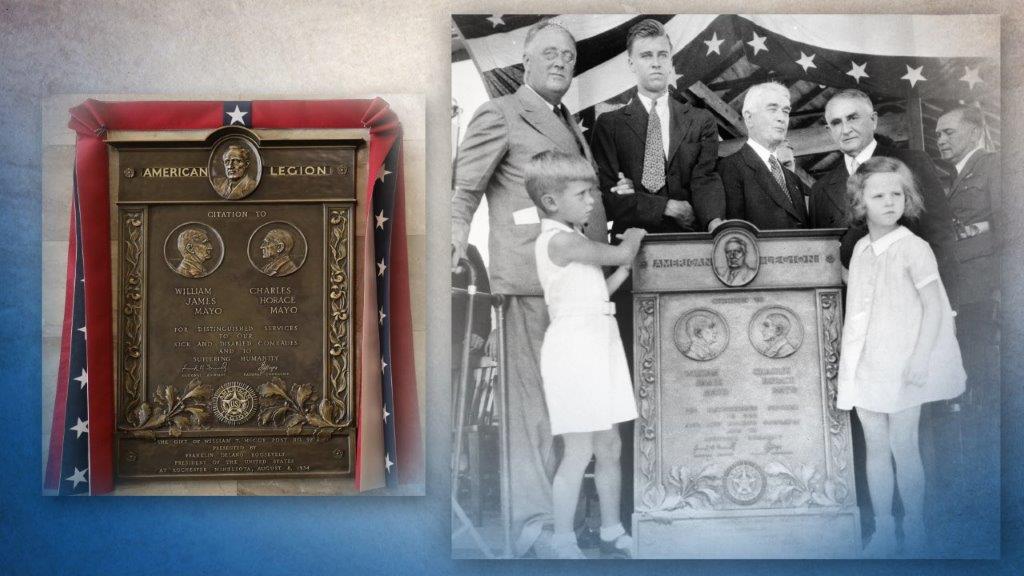

The plaque presented to the Mayos by President Franklin D. Roosevelt is on display in the lobby of the Plummer Building at Mayo Clinic in Rochester. The American Legion was honoring the brothers for the clinic’s charitable service to veterans of the American armed forces. At the ceremony, held at Soldiers Field to accommodate the huge crowd, the plaque was unveiled by the brothers’ grandchildren, Mildred (“Muff”) Mayo and Waltman Walters.

At a time when many American medical schools did not own a microscope, William Worrall Mayo, M.D., was using this one in his practice. It was manufactured by the Parisian firm Maison Nachet & Fils. The Mayo brothers donated this family heirloom to Mayo Clinic. Their father taught his young sons how to mount sections of tissue on glass slides to aid in diagnosis, including these specimens mounted by Charlie.

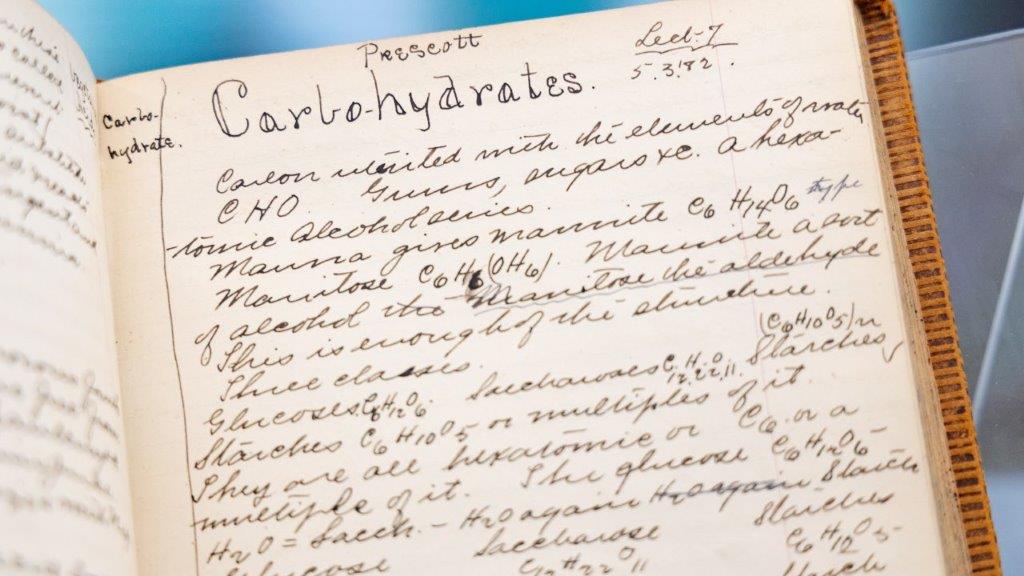

The Mayo brothers’ medical school notebooks are preserved in the Mayo Clinic Archives in Rochester. Their copious notes reflect the improving quality of medical education in late 19th-century America and the care with which their father chose their schools.

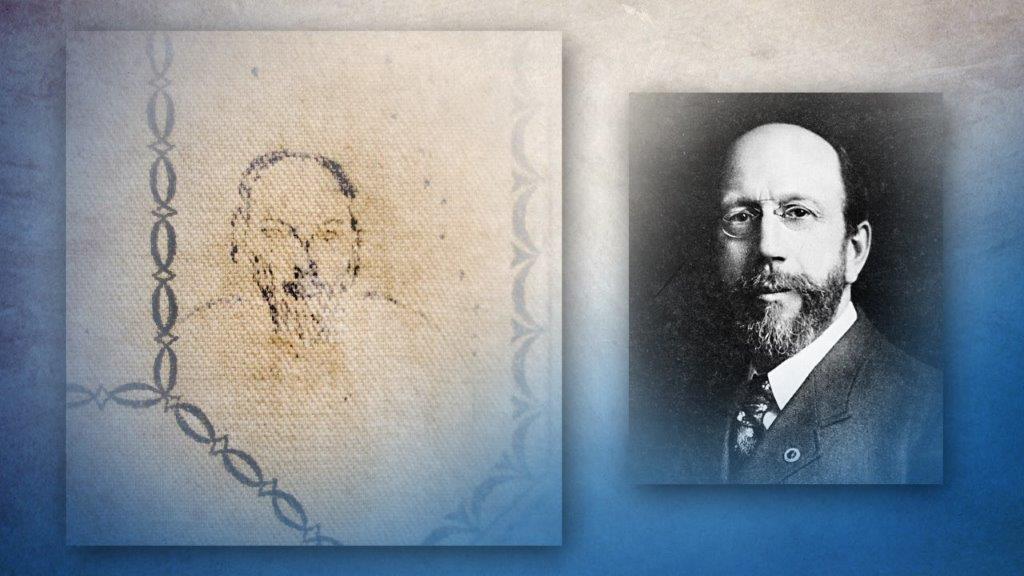

Charlie doodled on the cover of his notebook, sketching a portrait of his pathology professor, Frank S. Johnson, M.D.

Photo credit: University of Chicago Photographic Archive, [apf1-05266], Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

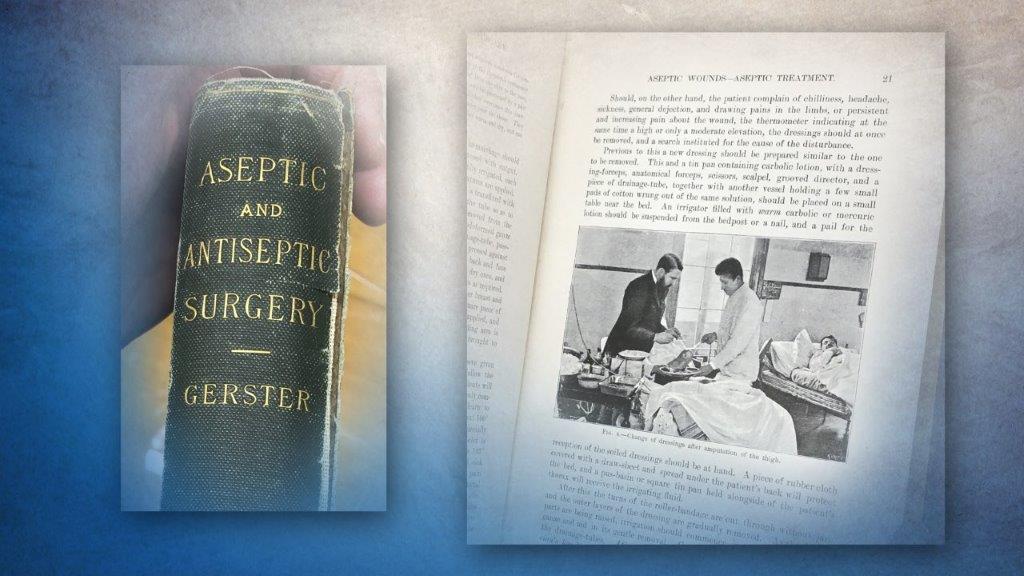

Soon after graduating from medical school, William J. Mayo, M.D., (“Dr. Will”) learned a new technique for preventing post-surgical infection from the Hungarian surgeon Arpad Gerster, M.D. It was instrumental in the Mayo brothers’ early success at Saint Marys Hospital. This rare first edition of Dr. Gerster’s instruction manual is from the Mayo family library. Dr. Will said he virtually committed the book to memory and credited it as one of the greatest influences on his surgical career.

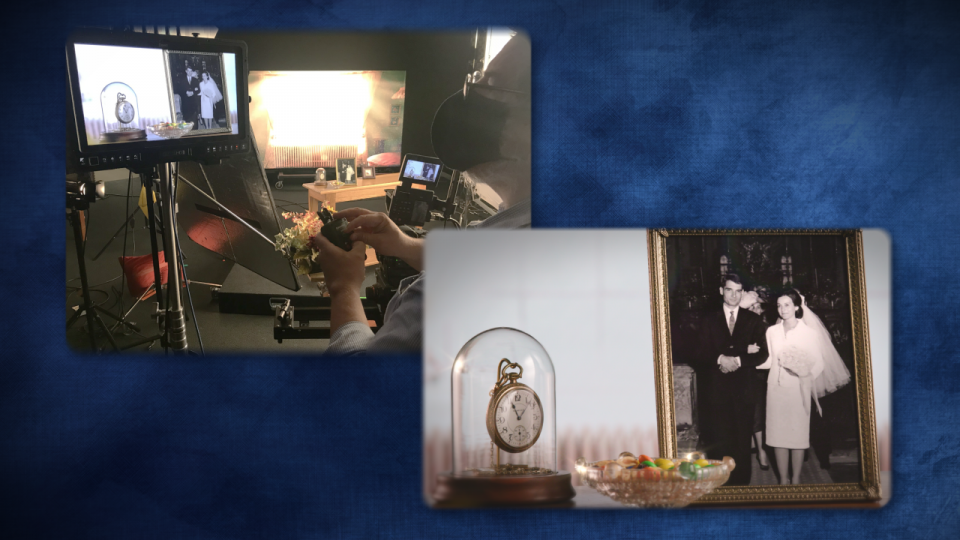

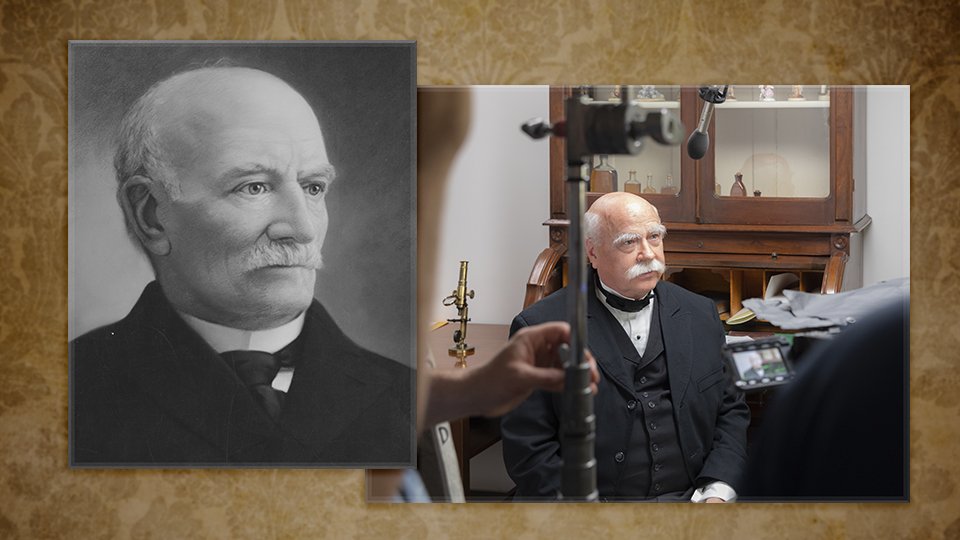

Historical artifacts were filmed in the Mayo Clinic studio in the Plummer Building. The first operating table used at Saint Marys Hospital was constructed in 1889 by Charles H. Mayo, M.D. (“Dr. Charlie”). It was based on a table he’d seen on his first trip to Europe, where he toured hospitals. One end was adjustable to accommodate various surgical positions for the patient. The tin pan underneath the patient caught the antiseptic liquids and boiled water which were liberally applied to prevent infections.

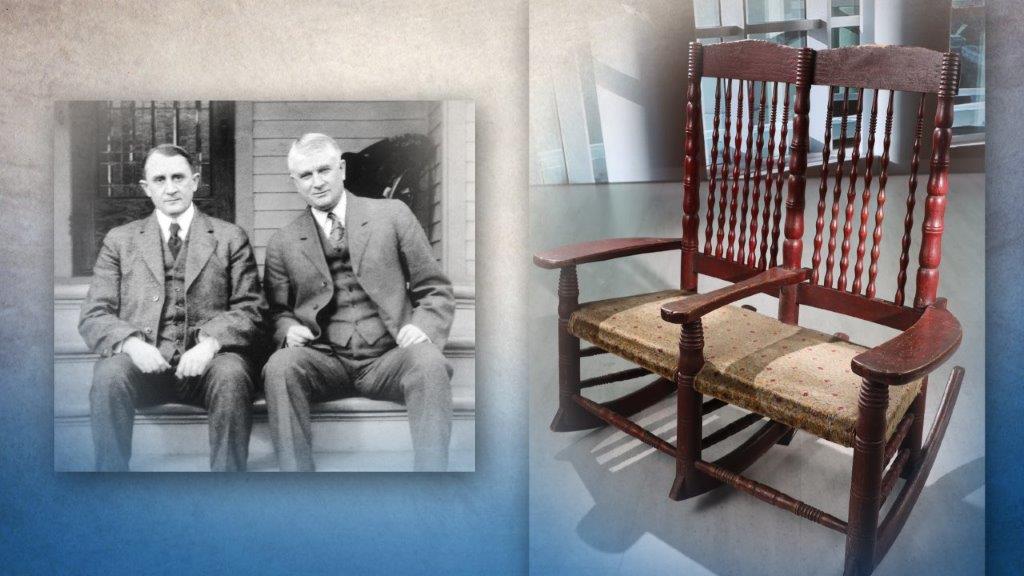

Will and Charlie began their married lives in houses next door to each other. In the evenings, the brothers would often sit together and talk in this double rocker on Charlie’s front porch. The chair is in the collection of the History Center of Olmsted County.

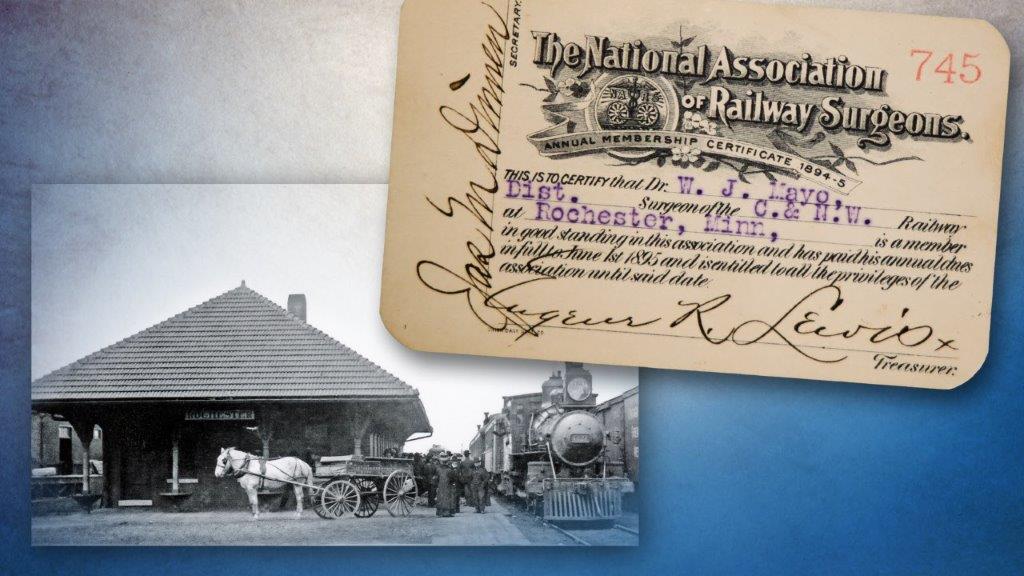

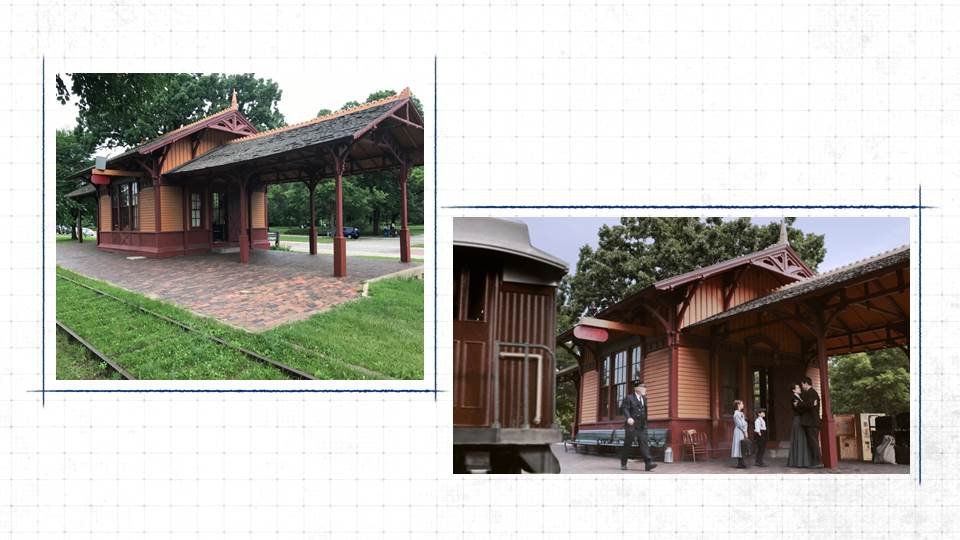

In the late 19th century, railroads contracted with regional doctors to ensure medical care was available all along the line in case of accidents or emergencies. Early in their careers, the Mayo brothers signed on as local surgeons for the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad that ran through Rochester. Railway surgery became a medical specialty that helped advance the treatment of traumatic injuries.

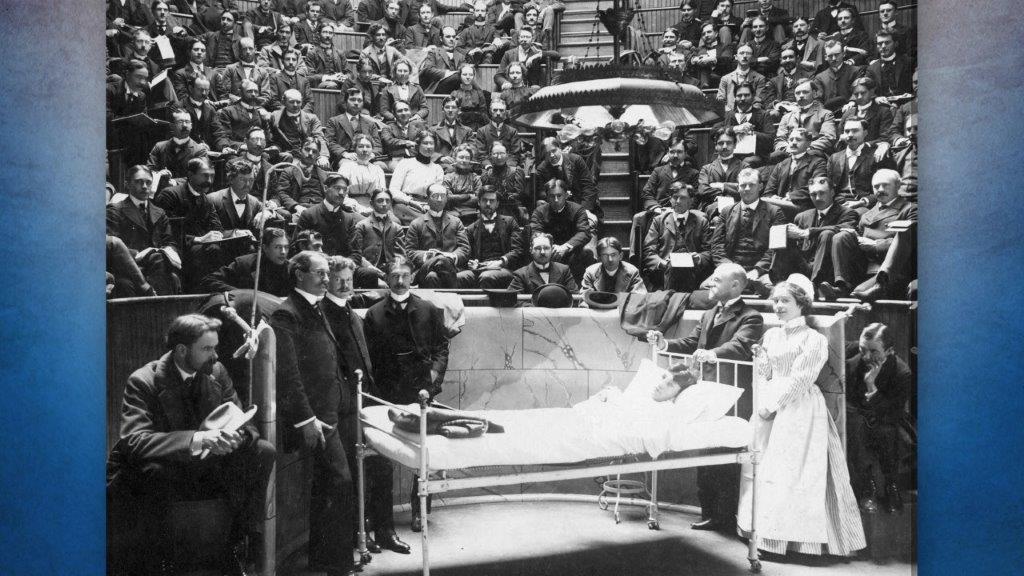

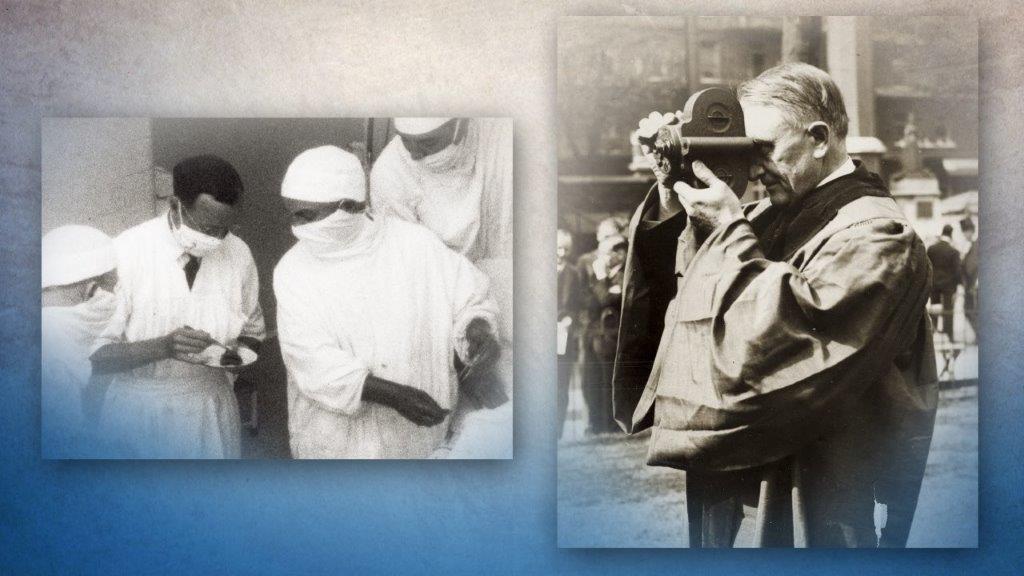

The Mayos traveled widely to learn the latest techniques in surgery. This 1900 photo depicts the teaching clinic of James B. Herrick, M.D., at Rush Medical College in Chicago. Ten years later, Dr. Will delivered the commencement address at this school, advising the graduates that “the best interest of the patient is the only interest to be considered.” It remains the primary value of Mayo Clinic.

Photo courtesy of Rush University Medical Center Archives

“An Adventure in Medicine” features new high-resolution transfers of films from the Mayo archives, some more than 100 years old. Most of them were filmed by doctors and other staff members, capturing glimpses of life at the clinic. Dr. Charlie, always enthusiastic about new technology, took a camera on his European travels.

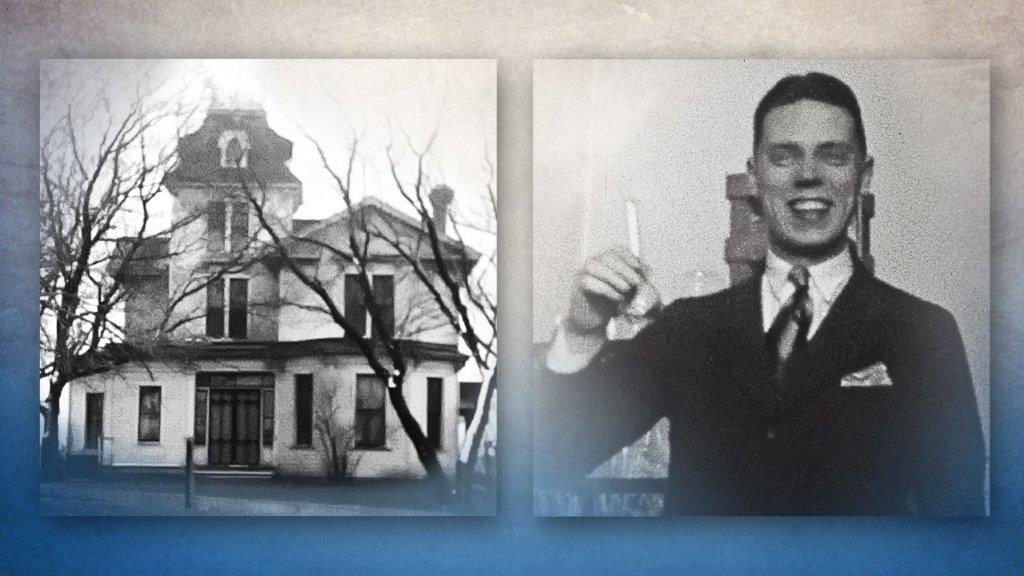

Among the images discovered in the films was a rare look at the farmhouse where the Mayo brothers grew up, featuring the tower built for their mother’s study of astronomy. Another film included a playful shot of the young Philip S. Hench, M.D., who would share a Nobel Prize in 1950 for the discovery of cortisone.

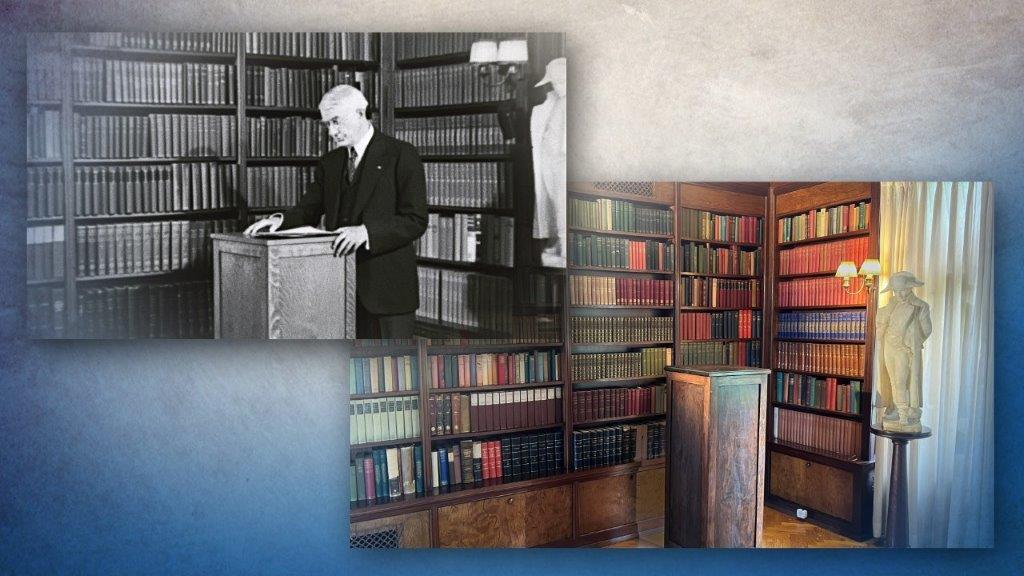

The only known sound film of Dr. Will was made in 1938 in the library of his former home by a crew from the University of Minnesota. He and his wife, Hattie, had recently donated the house to the Mayo Foundation as a place for people to “exchange ideas for the good of mankind.” Today, the historic site continues to serve Mayo Clinic as a meeting place. The lectern at which Dr. Will spoke is still there.

The bronze statues of the Mayo brothers seen at the beginning and end of the film were created by the Minnesota-born sculptor James Earle Fraser. This memorial, funded by donations from the people of Rochester and Olmsted County, was dedicated in 1952 with members of the Mayo family in attendance. It was designed to be a quiet place for “people of the world to ponder the benefits which accrued to mankind from the Mayos’ lives.”

A team at Mayo Clinic develops life-saving procedures and devices that give the Allies a decided advantage in World War II.

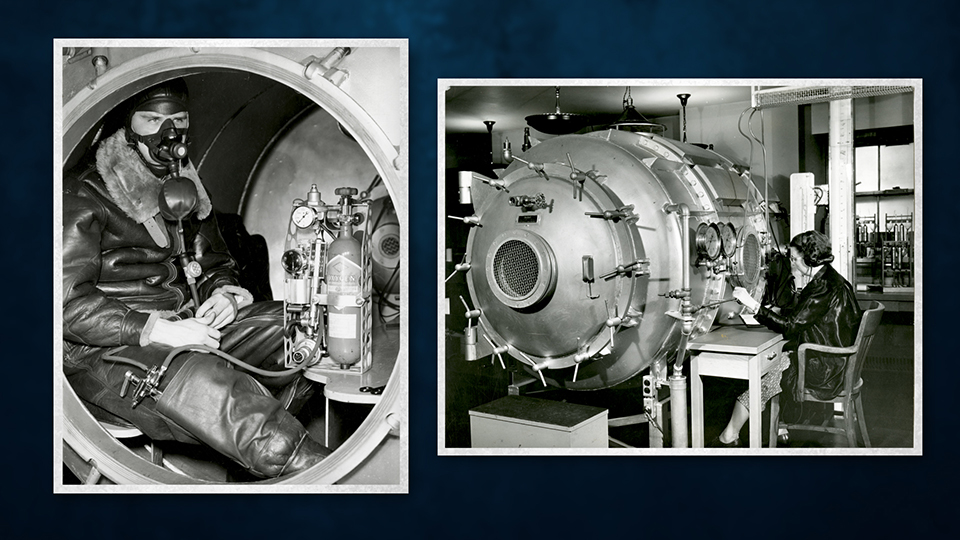

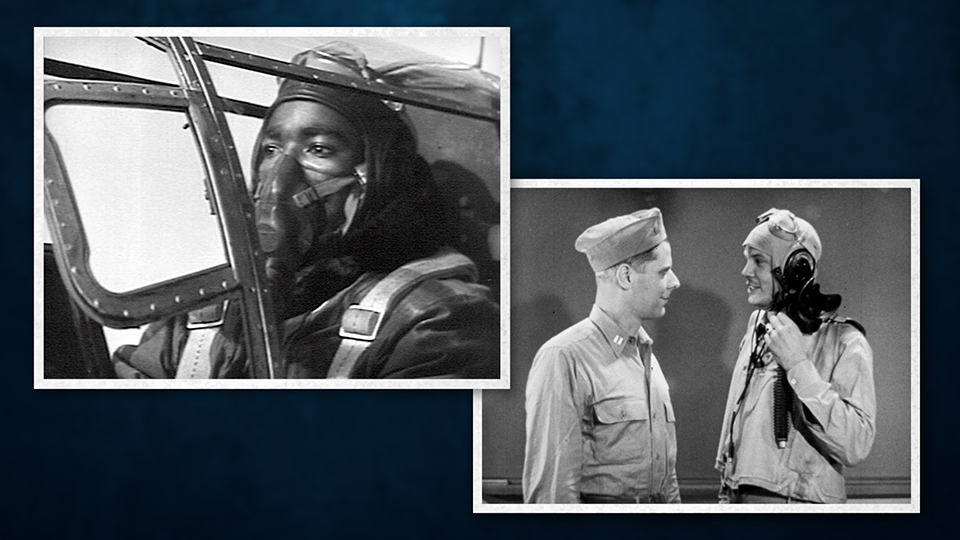

The Mayo Clinic Archives in the W. Bruce Fye Center for the History of Medicine has preserved over a hundred 16mm films documenting the work of the Mayo Aero Medical Unit in World War II. Selected reels were transferred at high resolution for inclusion in “Rising to the Challenge.” These images are from a film depicting an experiment in a low-altitude pressure chamber.

Subjects spent hours in the chambers, testing devices and breathing techniques in a simulation of high altitude. The winter gear on the airman in this chamber suggests he was also being exposed to the low temperature of unheated planes.

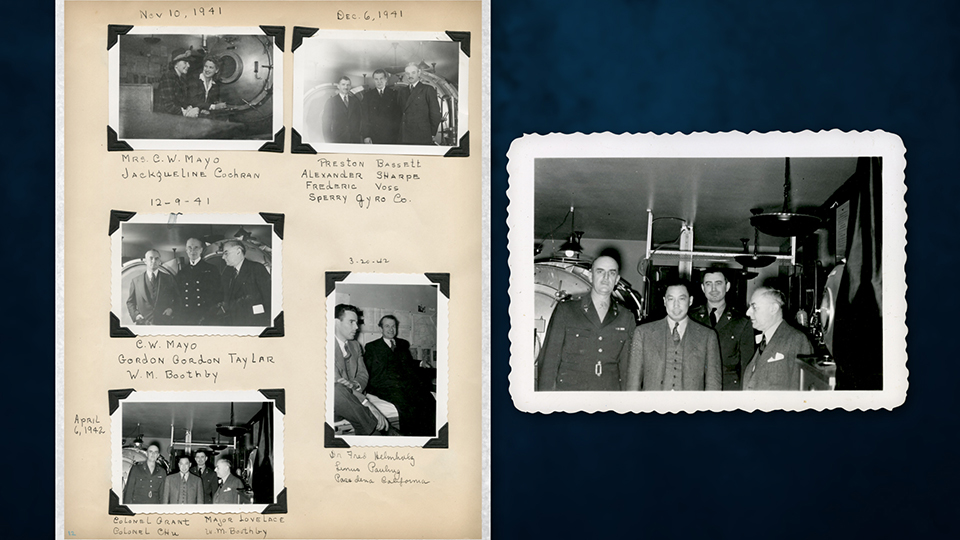

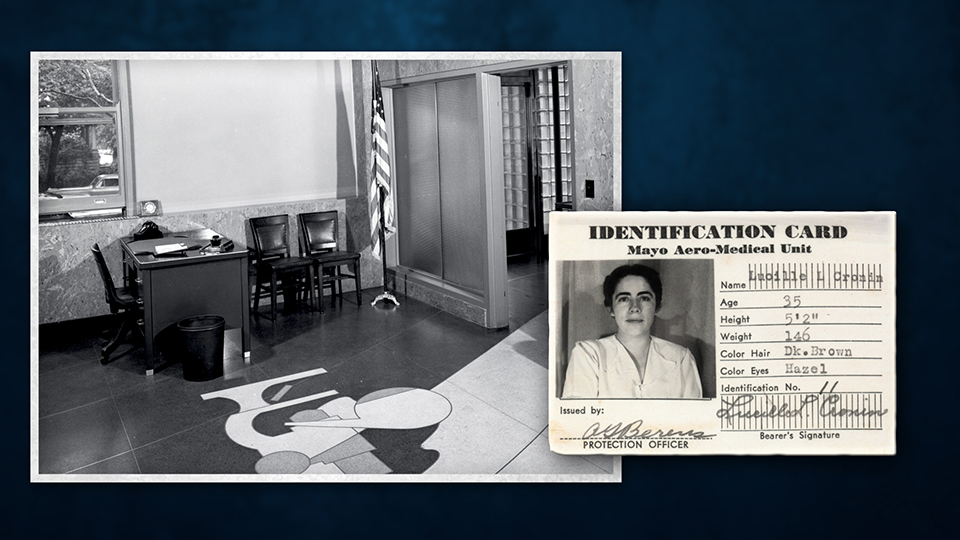

Throughout the war, Mayo collaborated with military, civilian and scientific partners. Walter M. Boothby, M.D., kept scrapbooks with snapshots of visitors to the Mayo Aero Medical Laboratory.

The government cautioned the Mayo researchers to be alert for enemy “espionage or sabotage.” All personnel were issued identification cards which were checked by a guard stationed in the lobby of the Medical Sciences Building. Mayo Clinic Security was responsible for fingerprinting and clearing civilian visitors.

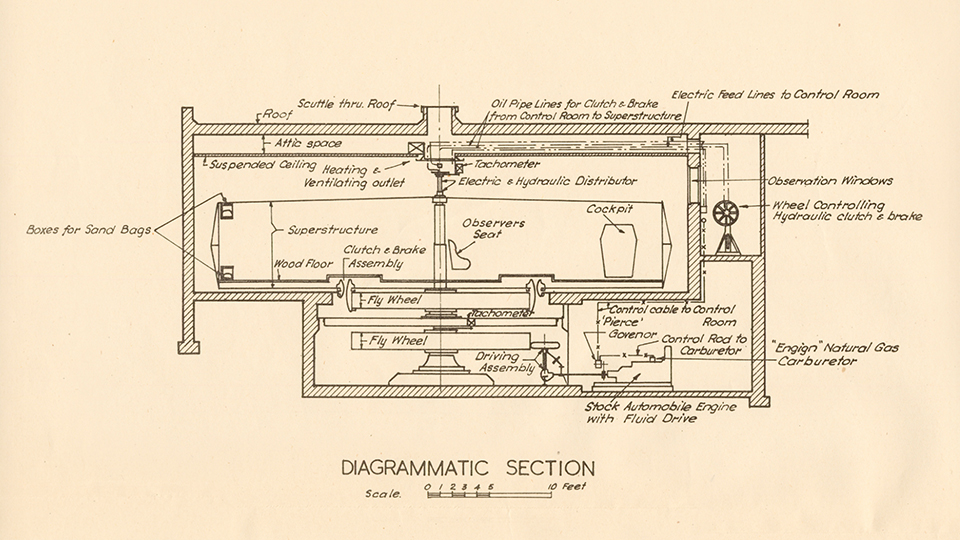

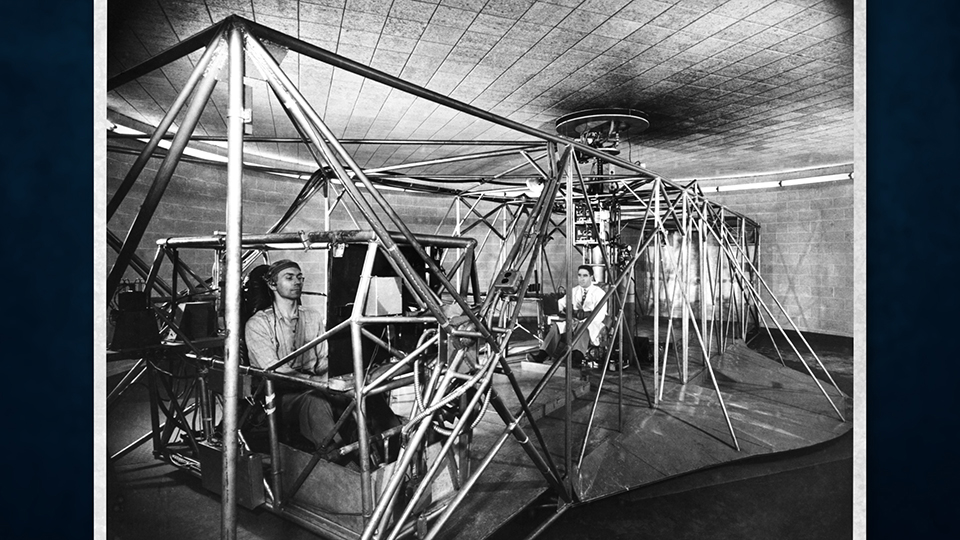

To accomplish their work, the team designed and constructed America’s first human centrifuge in a civilian laboratory. It was an invaluable tool in developing effective ways of countering the effects of G-force on pilots. Swiftly assembling the centrifuge in a time of war required ingenuity. The “stock automobile engine” specified on this plan was salvaged from a wrecked Chrysler.

Subjects riding the centrifuge wore devices that monitored a dozen body functions as the gantry spun. This enabled the researchers to amass an unprecedented amount of data on the effects of G-force on the human body. Physicians, technicians and military personnel were among the subjects who rode the centrifuge.

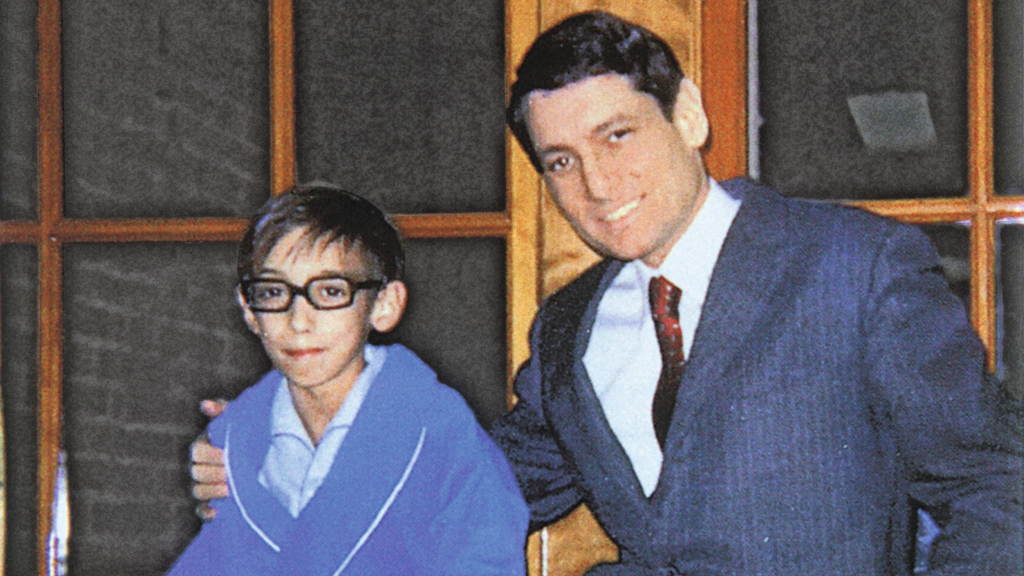

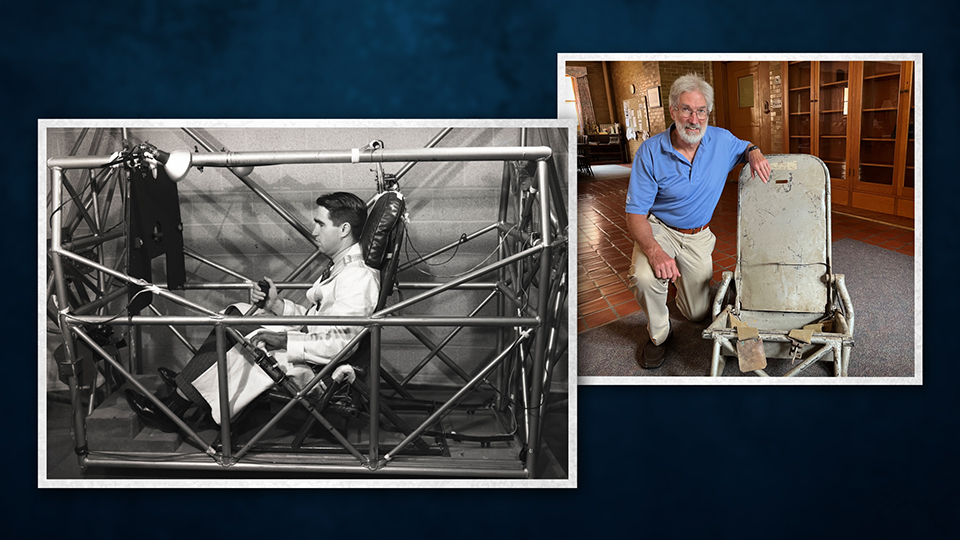

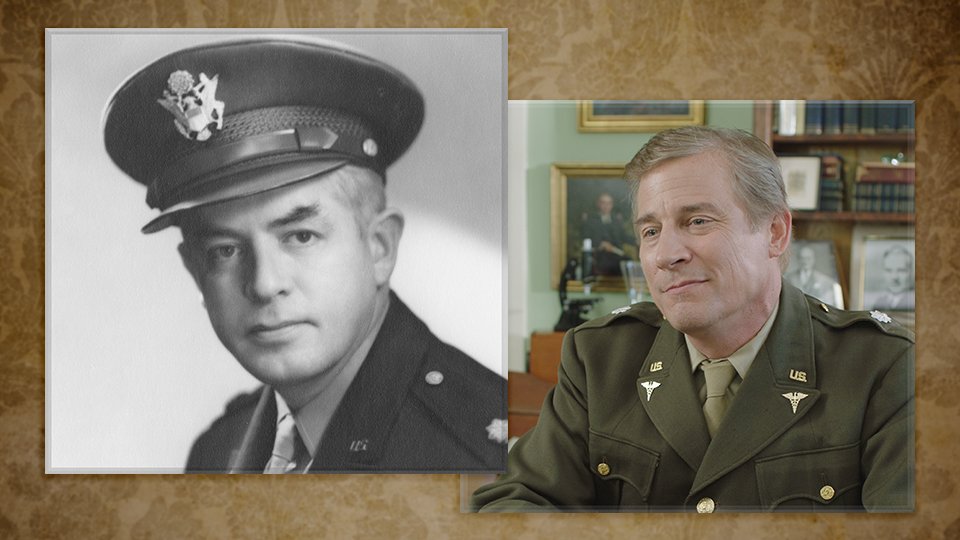

E. Andrew Wood, the son of Mayo physiologist Earl Wood, M.D., Ph.D., is seen here with the pilot’s seat from the centrifuge. The photo on the left shows Dr. Wood in that seat during the war-time research. Andrew has written a book about his father’s career titled “Life at High G-Force: The Quest of Mayo Clinic Researcher Dr. Earl H. Wood,” published by Mayo Clinic Press.

The owner of a Massachusetts garment company, David Clark, worked intensively with Dr. Wood to develop a G-suit to keep pilots from passing out in combat. Prototypes are modeled by technician Roy Engstrom (left) and engineer Ralph Sturm.

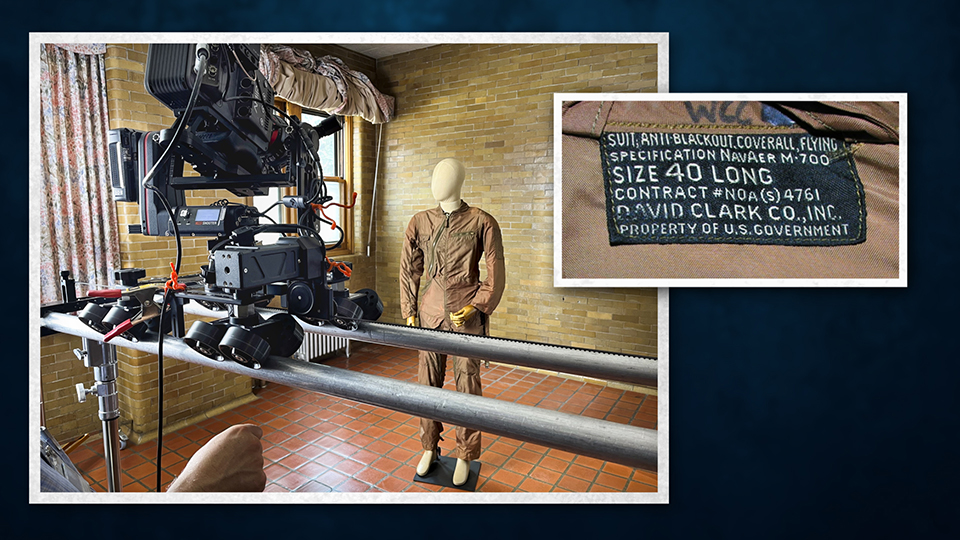

The film features artifacts of products developed by the Mayo Aero Medical Unit, including this G-suit. The label indicates it was one of the first batch ordered from the David Clark Company by the U.S. Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics. It still contains the rubber bladders sewn into the legs and abdomen.

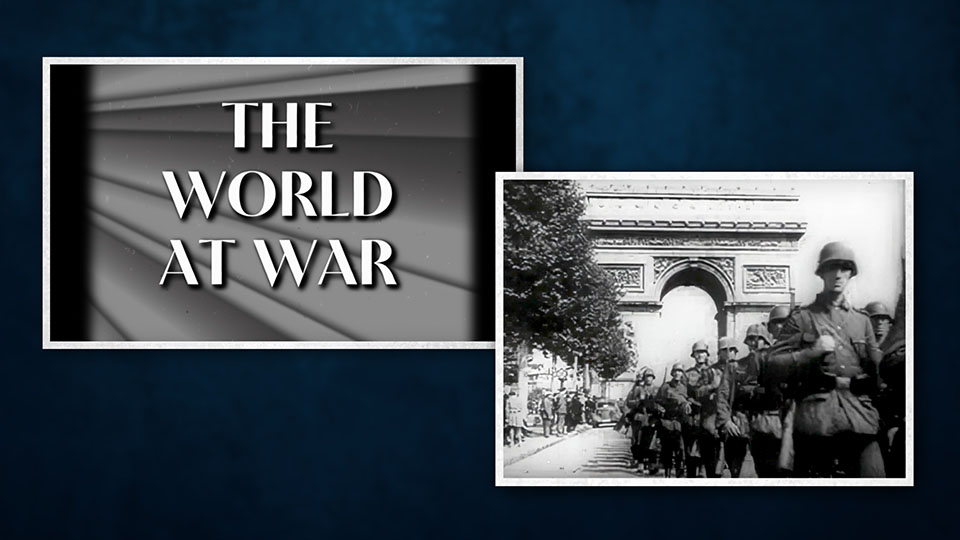

In the 1940s, newsreels were often shown in movie theaters before the feature film. They were very popular with a public avid for the latest war news. For “Rising to the Challenge,” newsreels in the style of the period were created to introduce the main topics of the story.

“Rising to the Challenge” includes scenes from films produced by the U.S. government during World War II. The image on the right is from a film introducing flight crews to the A-14 oxygen mask developed at Mayo Clinic, described by the instructor as “the best oxygen mask we’ve ever had.”

The Type A-14 oxygen mask became standard issue for pilots in the U.S. Army Air Forces in 1943. It was the result of extensive testing with more than a thousand experimental masks. One of the archival films in “Rising to the Challenge” shows the process Arthur H. Bulbulian, D.D.S., used for making the prototypes.

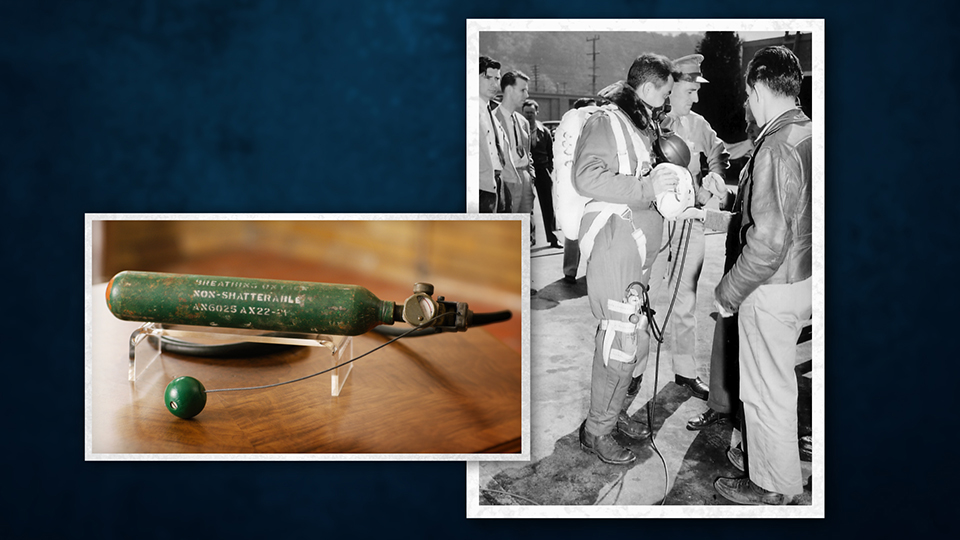

The team developed an improved bailout bottle for high-altitude parachute jumps. Pulling the so-called “green apple” instantly opened the oxygen container, saving precious seconds. In this photo from a declassified government report, William R. Lovelace II, M.D., wears the bottle on the leg of his flight suit as he prepares to test it on a record-setting parachute jump.

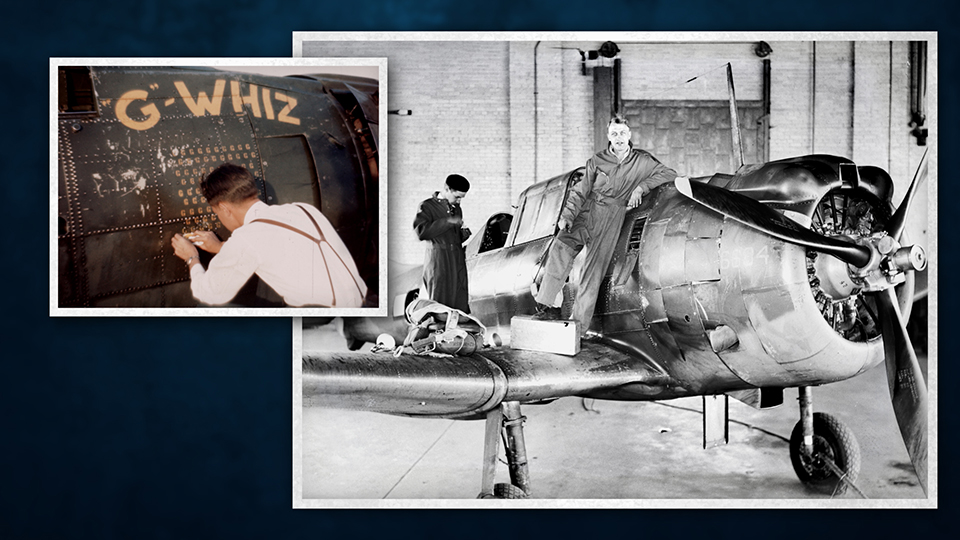

The U.S. Army Air Forces loaned Mayo a used (and disarmed) Douglas Dauntless dive bomber for airborne experiments. The plane was named the G-Whiz. A “G” was stenciled on the fuselage after every test flight.

The centrifuge and pressure chambers are gone, but aerospace medicine research continues at Mayo Clinic using the latest technology. “Rising to the Challenge” includes scenes of a programmable rotating chair (left) and a high-altitude stress test filmed at Mayo Clinic in Arizona.

In 1973, Mayo Clinic offers its patients a revolutionary advance in brain imaging.

Learn more about the people, historic documents, and re-creations featured in the film.

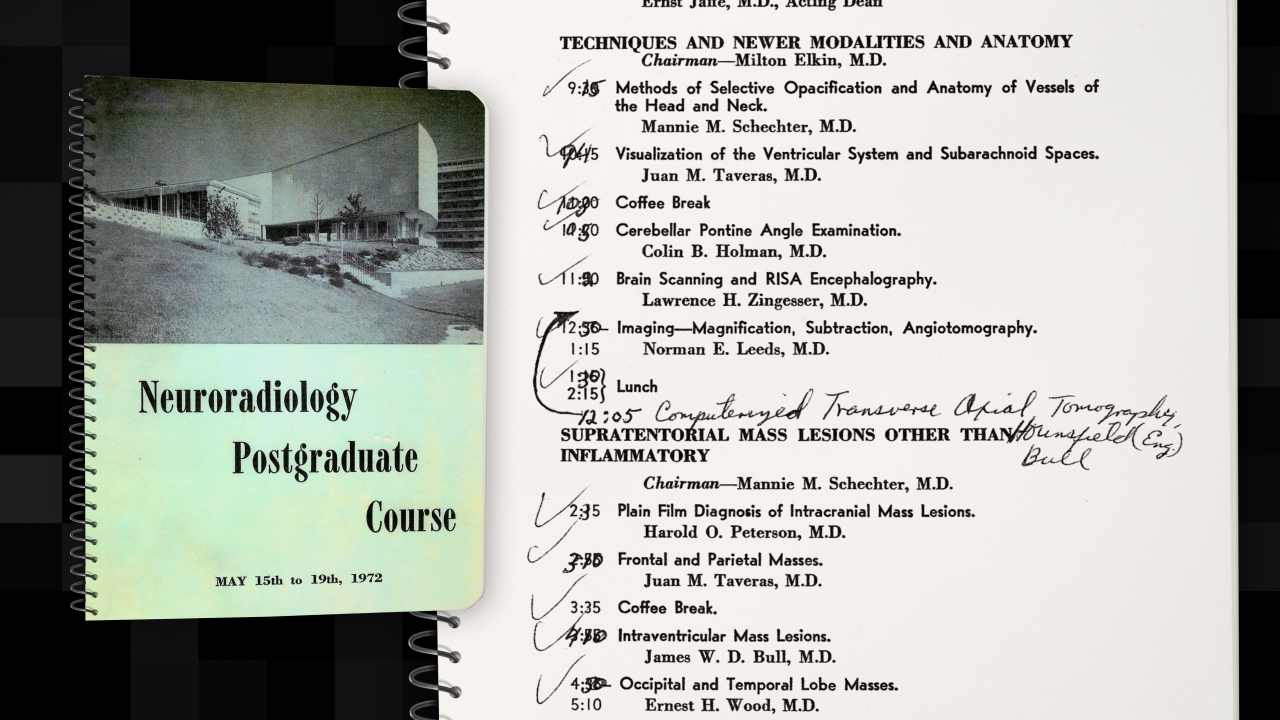

This program from a 1972 educational course was provided by a radiologist who attended. His notes show how the schedule was adjusted at the last minute to make room for Godfrey Hounsfield, the British inventor of the CAT scanner. One of the other speakers that morning was Colin B. Holman, M.D., of Mayo Clinic. He borrowed slides of CAT scans from Hounsfield to share with his colleagues back in Rochester, Minnesota, setting in motion Mayo’s eventual purchase of the first CAT scanner to be used in North America.

Mayo Clinic archivists helped recreate a 1970s exam room in the Mayo Building for the film’s opening scenario. The set included a vintage X-ray view box and period-appropriate furnishings.

A re-creation of the first viewing of CAT scans at Mayo Clinic was filmed in the room where it actually happened on the second floor of the Mayo Building. In 1972, it was the break room for the Radiology department. Prior to that, it was the Board of Governors meeting room. It has since been remodeled, but remnants of a leather-covered wall can be seen on the door.

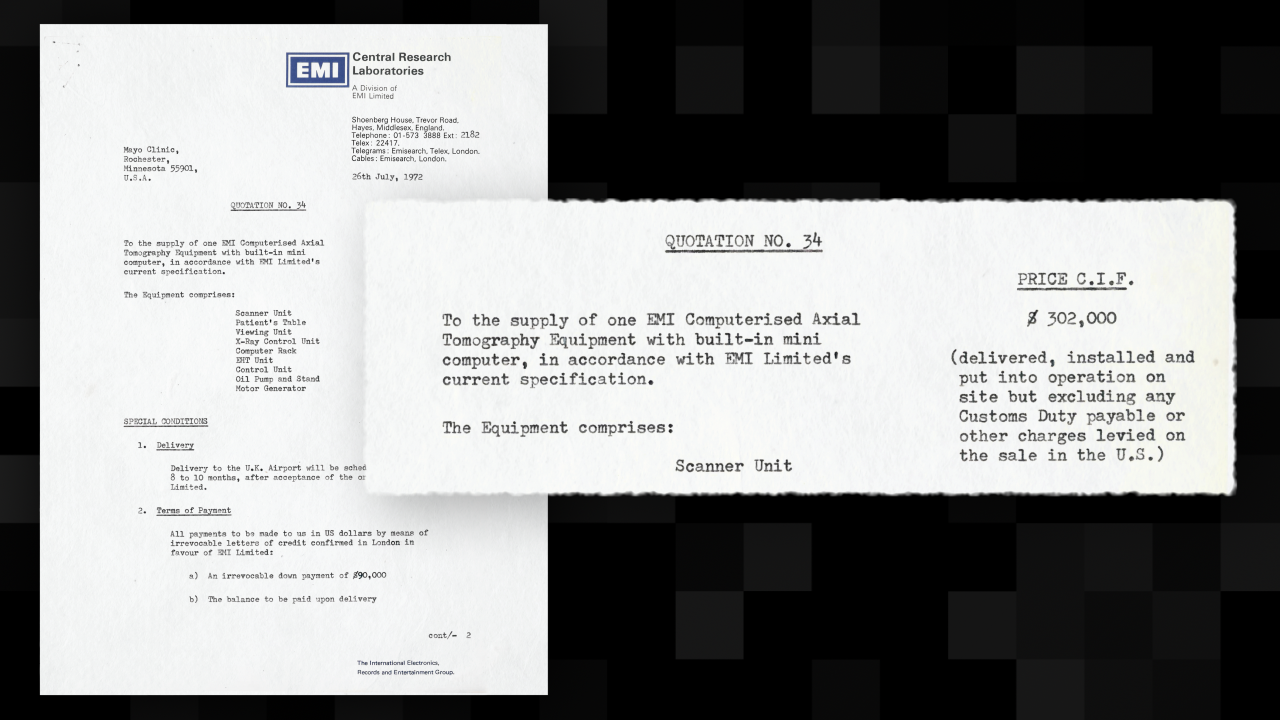

Documents from the Mayo Clinic Archives in the W. Bruce Fye Center for the History of Medicine helped tell the story. This is the quotation document EMI sent after Hillier L. Baker, Jr., M.D., traveled to England to evaluate the prototype CAT scanner and place the first American order. The $302,000 cost is equivalent to more than $2,000,000 today.

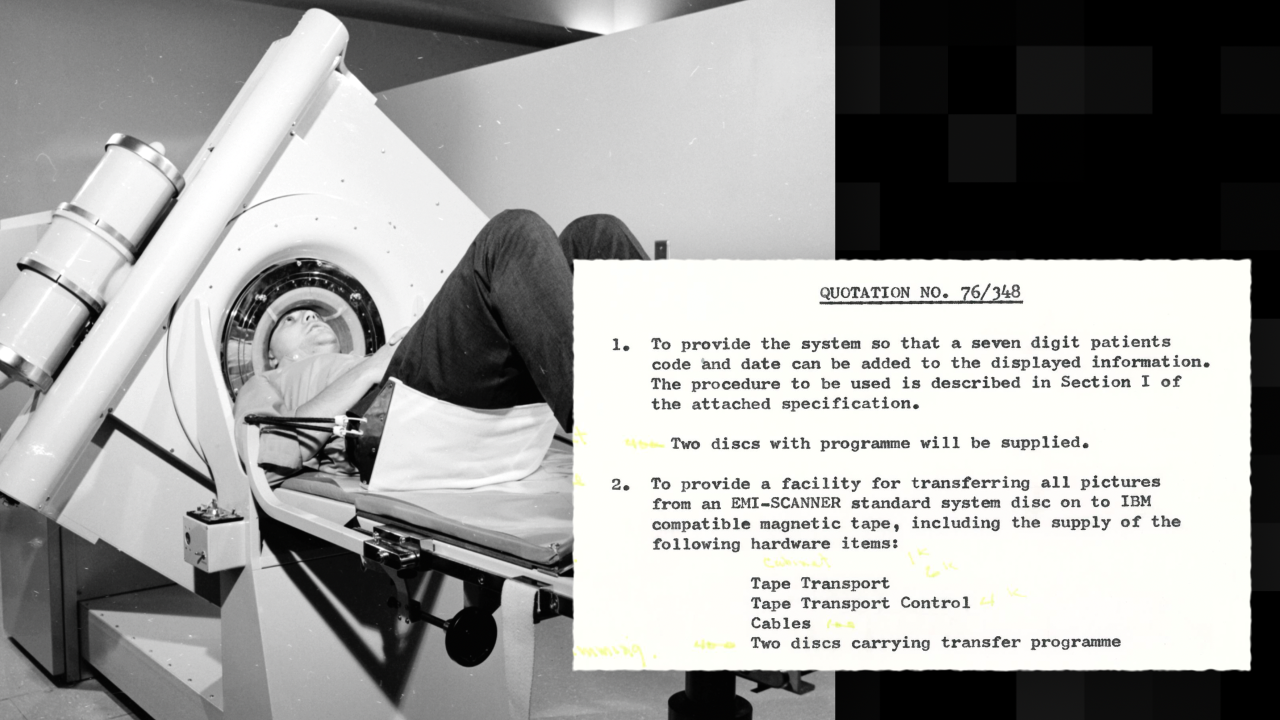

As Mayo’s scanner was being constructed, Mayo neuroradiologists requested a number of enhancements to facilitate serving patients and conducting research. The changes they suggested made it possible to display more text information on a scan and more easily store and retrieve scans. EMI subsequently made these features available to all their customers.

EMI sent employees from England to Mayo Clinic. They included the scanner’s inventor, Godfrey Hounsfield (in a color snapshot provided by his nephew), and engineers Dave King and Peter Clarke, seen here installing the scanner. In a progress report to EMI, Clarke wrote, “I feel I am among friends. Everyone here is very friendly and helpful and I have open invitations to visit several people.”

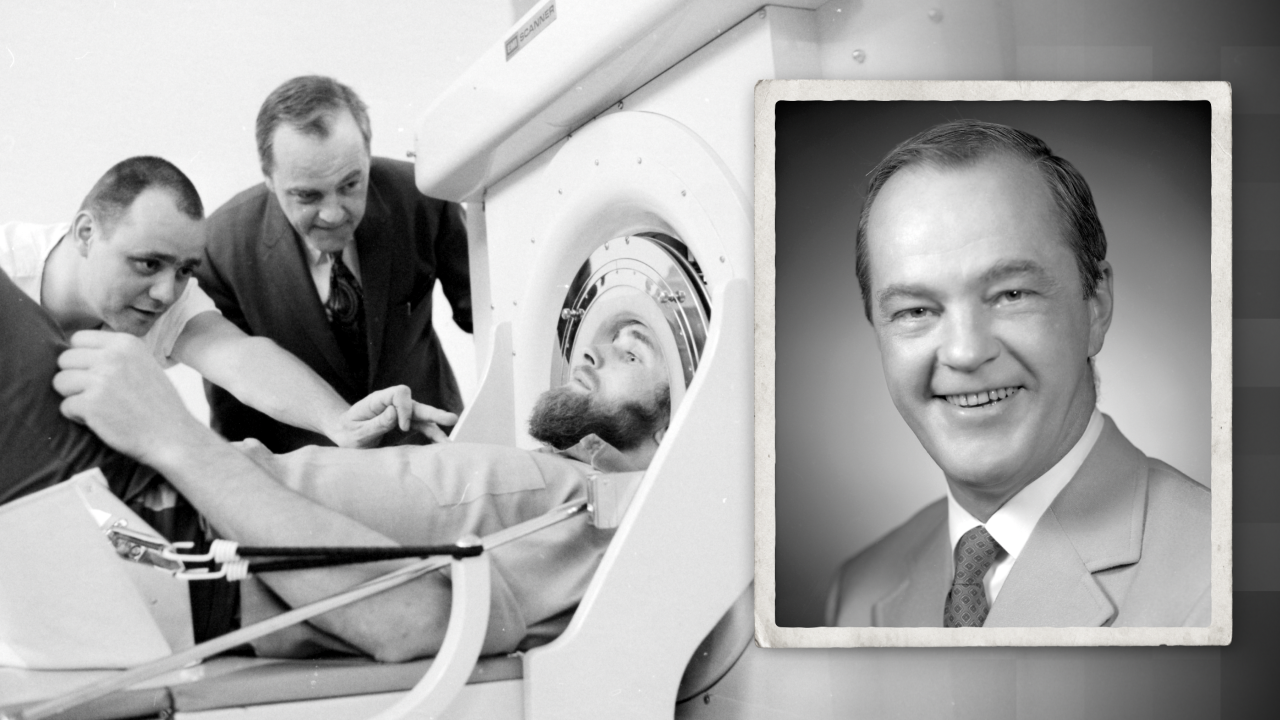

Hillier L. Baker, Jr., M.D., took an enthusiastic leadership role in helping Mayo acquire the first CAT scanner in North America. Dr. Baker’s early research and publications on the effectiveness of CAT scanning were credited with helping the technology become quickly established as a new standard of care. He is seen here with EMI engineer Dave King (in the scanner) and Darrel Holtz, the first American scanning technologist.

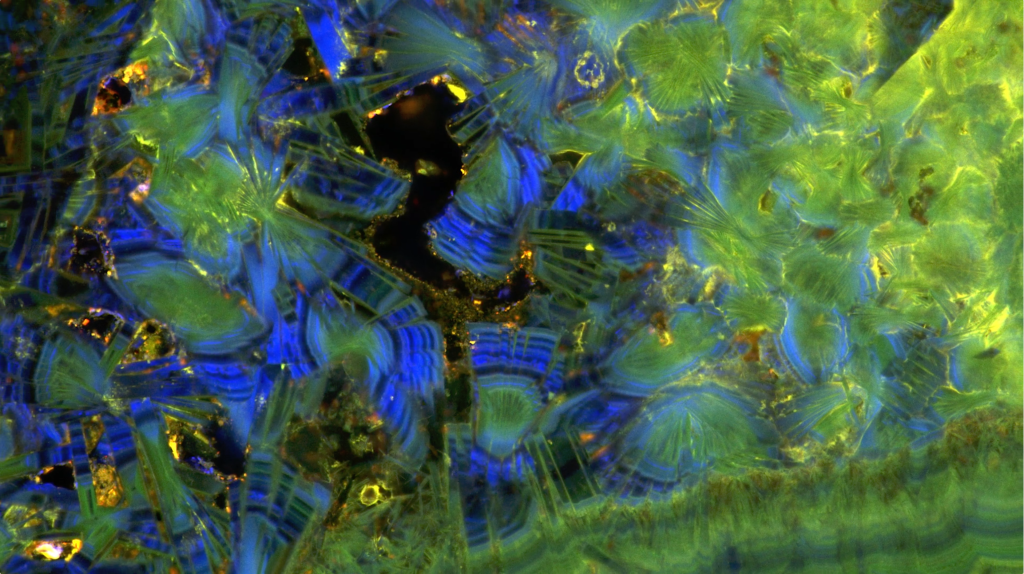

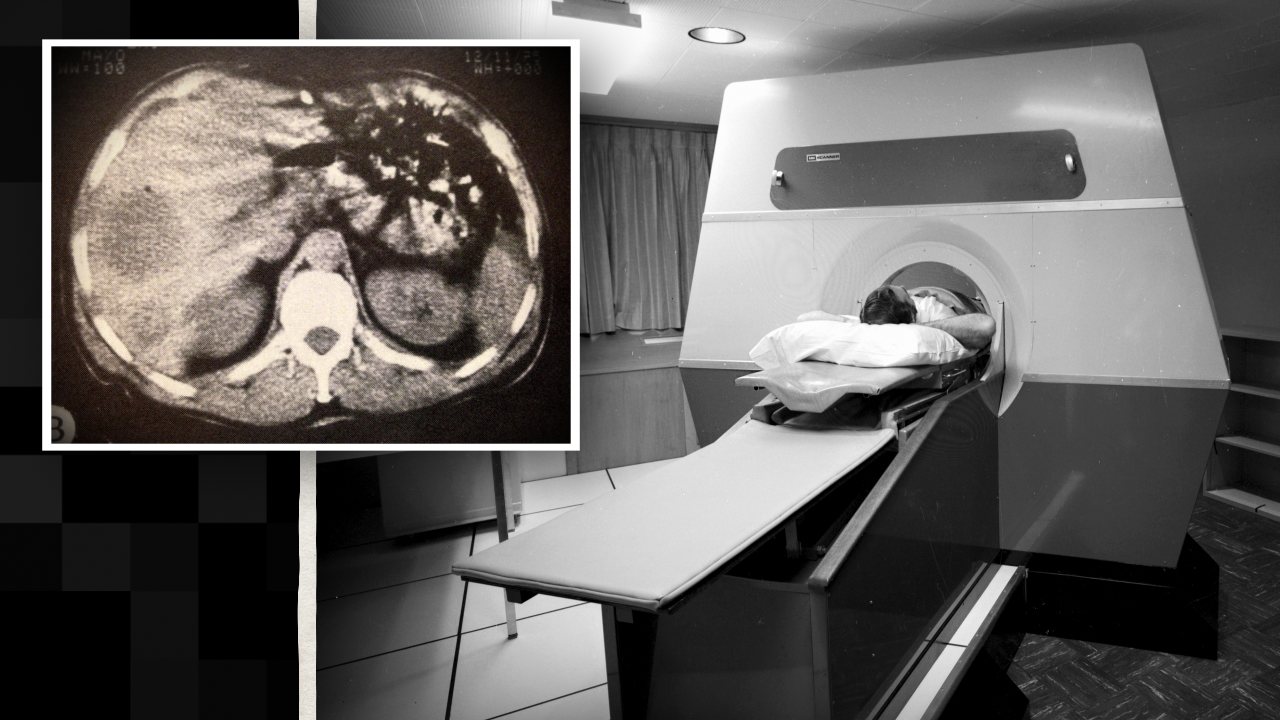

After becoming an early adopter of the EMI-Scanner, Mayo had an ongoing collaborative relationship with EMI. In 1975, a prototype of the company’s new body scanner, a major advance in radiology, was installed at Mayo. This image is an abdominal scan taken on the machine EMI code-named “Emerald.”

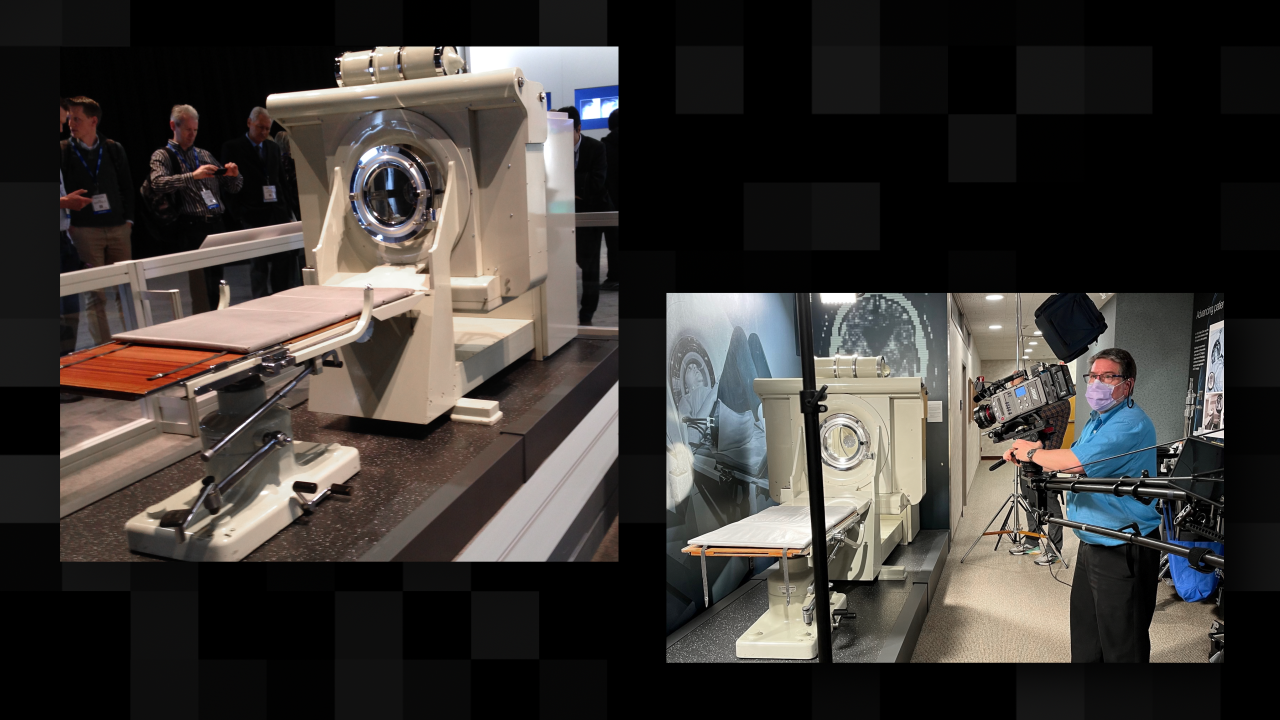

Mayo’s device is one of the last remaining examples of the first generation of CAT scanners. In 2014, it traveled to Chicago for the 100th annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America. Today, the scanner is on display in the Radiology department on the second floor of the Mayo Building. It is shown here being filmed to mark the 50th anniversary of its arrival at Mayo Clinic.

Mayo Clinic assists with the return of an endangered species.

A 56-bell musical instrument adds a unique element to Mayo’s healing mission.

A natural disaster brings a community together to build a hospital.

Years of persistent research lead to a landmark in medicine and the Nobel Prize.

Discover the stories behind the film’s unique images, locations and historic items.

A corner of the 16th floor of the historic Plummer Building at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, made an appropriate background for laboratory recreations. It has changed little since the building opened in 1929. Currently used for library storage, it was originally an endocrinology laboratory, the medical specialty concerned with hormones—including cortisone.

This desk, custom-made for the Plummer Building in 1929, was acquired by former employee Bob Garrity during building renovations in the 1970s. He and his wife, Mary Jo, donated the table to Mayo Clinic during the production of this film. It returned to the Plummer Building, standing in as a laboratory bench.

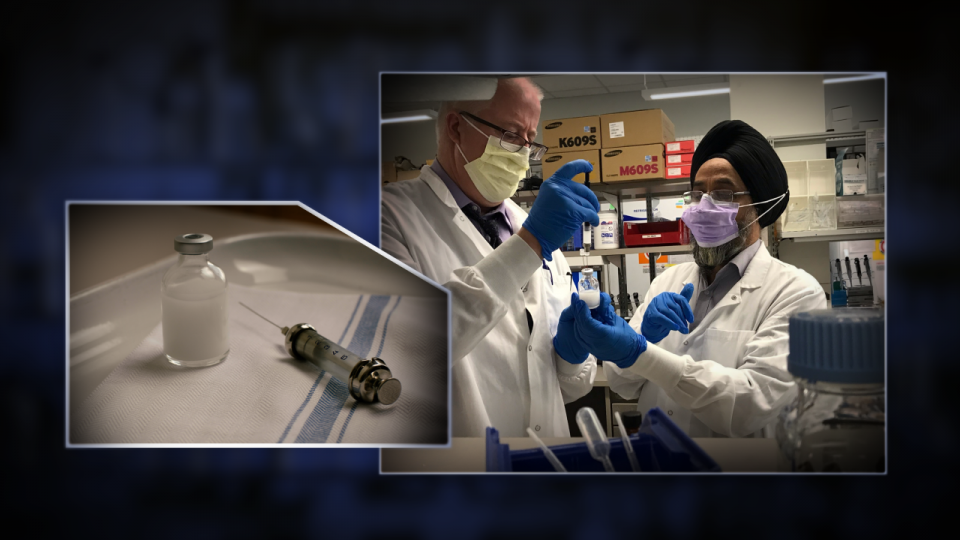

Ravinder J. Singh, Ph.D. (right), director of the Mayo Clinic Endocrine Laboratory, and Robert L. Taylor of Mayo Clinic’s Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology served as the film’s laboratory consultants. Here they are seen preparing a solution that resembles the vial of cortisone used in the original clinical trials.

To represent Dr. Edward C. Kendall’s discovery of thyroxine in 1914, the film’s laboratory consultants used a similar process in a contemporary laboratory to isolate thyroxine crystals in a vintage flask.

Steven M. Anderson (right), Mayo Clinic’s glassblower, seen above with the film’s laboratory consultant, Ravinder Singh, Ph.D., provided glassware from his extensive collection for laboratory scenes spanning the years 1914 to 1949.

During the 1930s, the Swiss biochemist Dr. Tadeus Reichstein (above) and Dr. Kendall were simultaneously investigating adrenal hormones. In the spirit of scientific cooperation, Dr. Reichstein sent samples of a dozen substances he had isolated to Dr. Kendall. These rarely seen artifacts, preserved in the Mayo Clinic Archives of the W. Bruce Fye Center for the History of Medicine, were used in the film to represent Dr. Kendall’s compounds A through F.

The film includes many photos from the Mayo Clinic Archives. The graphic designer used a program that utilizes artificial intelligence to colorize black-and-white images. She consulted contemporaneous portrait paintings and Mayo historic buildings for color reference.

Scenes were filmed in Plummer Hall, the location of the 1949 presentation by Dr. Kendall and his collaborator, Philip S. Hench, M.D., announcing the results of the clinical trials of cortisone. Several scenes were carefully framed to match present-day scenes with period photographs (seen above on right) for a “then-and-now” effect.

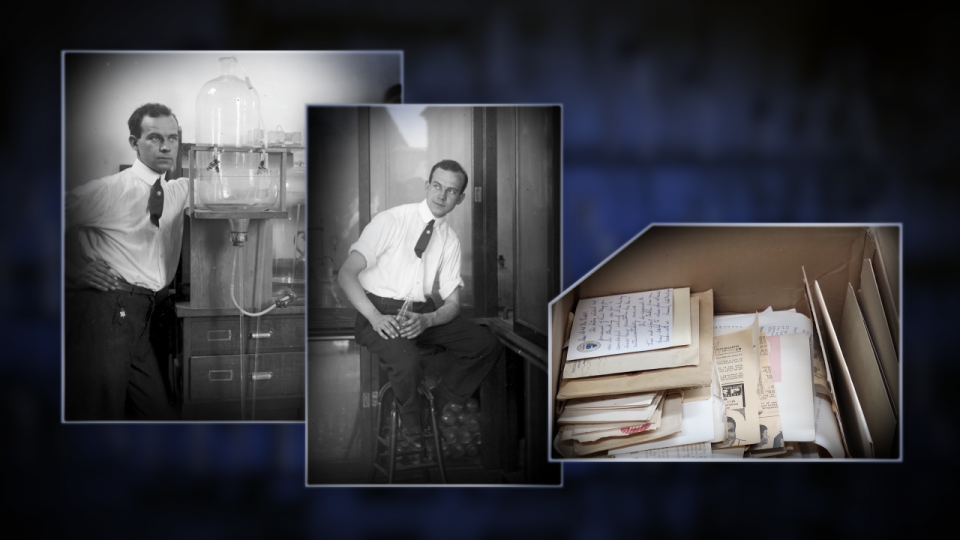

As the film was in production, Dr. Kendall's grandchildren donated hundreds of photographs, papers, and artifacts to the Mayo Clinic Archives. The film includes rarely seen photos of Dr. Kendall from this collection.

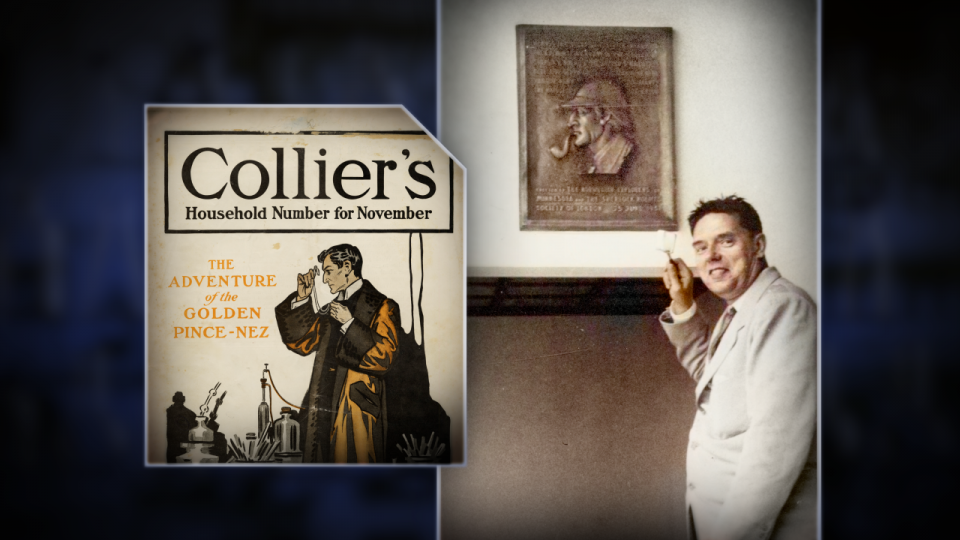

Dr. Hench, a Sherlock Holmes enthusiast, was involved in placing a plaque near the site of one of the detective’s fictional adventures in Switzerland. His world-class collection of Sherlock Holmes first editions and memorabilia was donated to the University of Minnesota Libraries. It includes this 1904 illustration of Holmes in a laboratory.

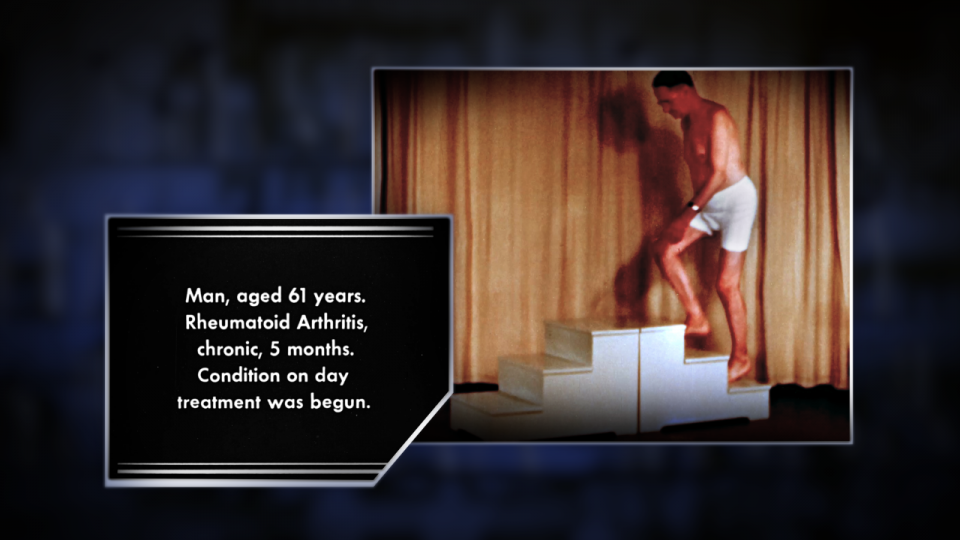

As the cortisone clinical trials were conducted, Mayo Clinic’s audio-visual department filmed the patients demonstrating the dramatic effects of the drug on their arthritic symptoms. Consent forms signed by the patients were located in the Mayo Clinic Archives.

The recreation of the 1949 staff meeting in Plummer Hall called for a vintage film projector. The model above, held in the Mayo Clinic Archives, was restored to working condition by Kevin E. Bennet, Ph.D., administrator of the Division of Engineering.

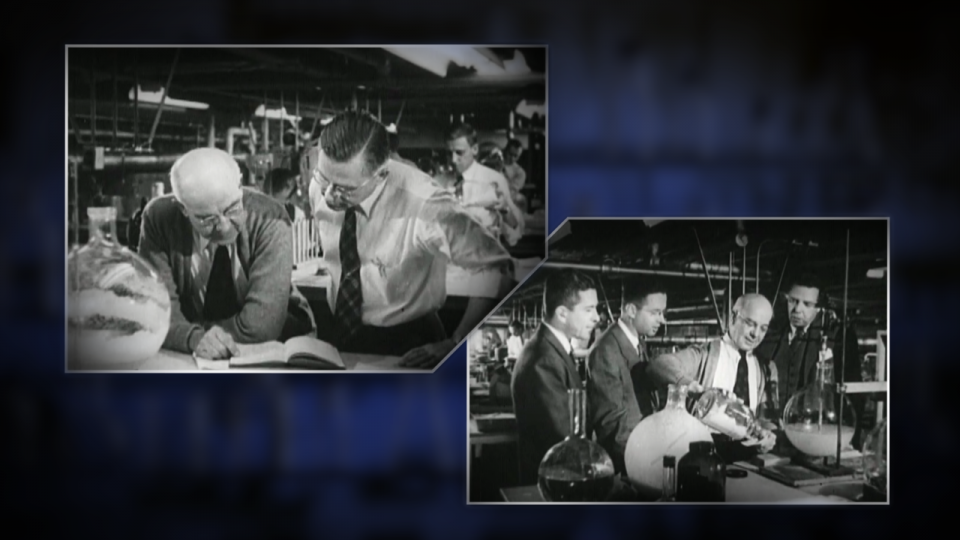

While researching the film, the scriptwriter saw a reference to a 1949 promotional film produced by the American Medical Association that featured the cortisone research. An extremely rare copy of the film was located in the archives of Duke University Medical Center. It contains the only known motion footage of the cortisone team in Dr. Kendall’s laboratory.

Dr. Kendall donated to Mayo Clinic the ornate certificate and gold medal he received at the Nobel Prize ceremony in Sweden. The Department of Facilities, Mayo Paint Shop, made a mold from the medal to cast a realistic replica for the filming. The original medal is on display in the Mayo Clinic Historical Suite on the third floor of the Plummer Building.

The skill and values of the Doctors Mayo and their colleagues make the Mayo name synonymous with medical excellence.

Go behind the scenes to learn more about the unique locations and historic images featured in the film.

The first building to bear the name Mayo Clinic opened in 1914. When it was demolished seventy years later, the carved stone over the door was buried in a landfill. In the 21st century, this lintel was excavated and installed above the door of Mayo Clinic Heritage Hall on the Rochester campus near its original location.

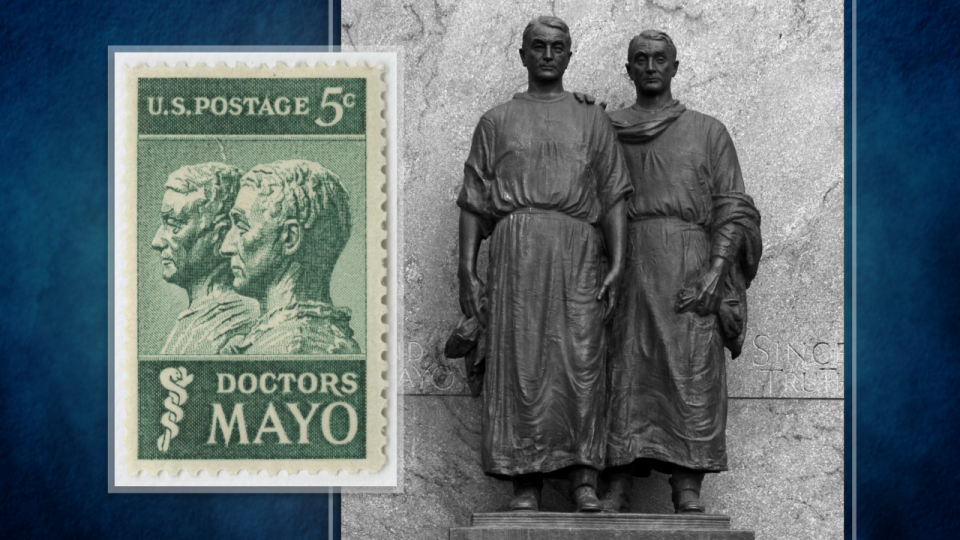

As Mayo celebrated its centennial year in 1964, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp honoring the Mayo brothers. The illustration is based on a 1952 bronze statue by James Earle Fraser, creator of many public sculptures in Washington, D.C., and elsewhere. This sculpture of the Mayo brothers now stands at the Mayo Civic Center in Rochester.

From its beginning, the Mayo’s practice was based on teamwork. This rare 1911 photo includes Dr. William J. Mayo (center, in surgical cap), with Sister Joseph Dempsey, his first assistant and the longtime supervisor of Saint Marys Hospital to his right. Alice Magaw, a pioneering nurse anesthetist, is seated below Sister Joseph.

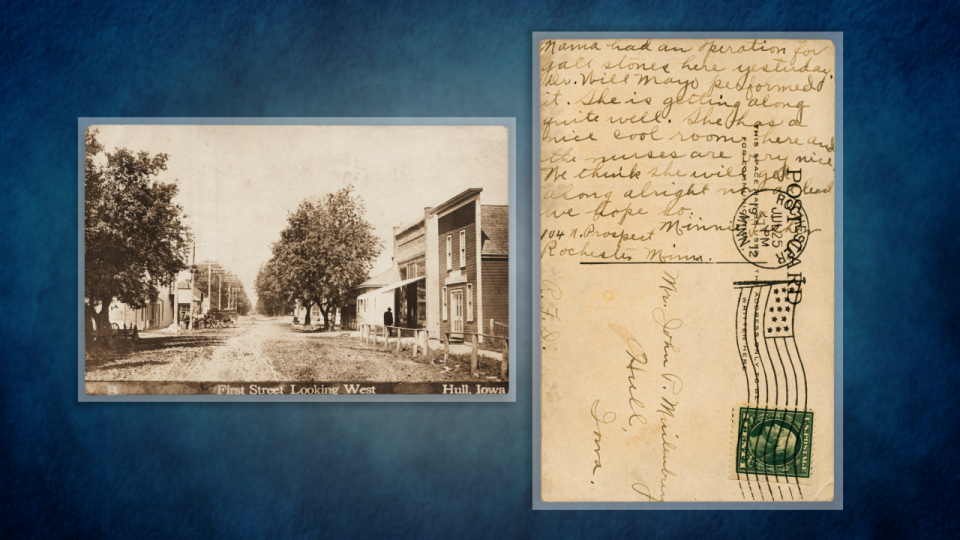

In 1912, a woman from the small town of Hull, Iowa brought her mother to Mayo Clinic for surgery. Her descendants recently donated a postcard “Minnie” wrote documenting that visit.

The W. Bruce Fye Center for the History of Medicine holds a large collection of Mayo-themed souvenirs going back to the clinic’s earliest years. Among them are this plate with an illustration of the Mayos’ first offices in the Masonic Temple building and a thermometer and tape measure with illustrations of the 1929 building that was later named for Dr. Henry S. Plummer.

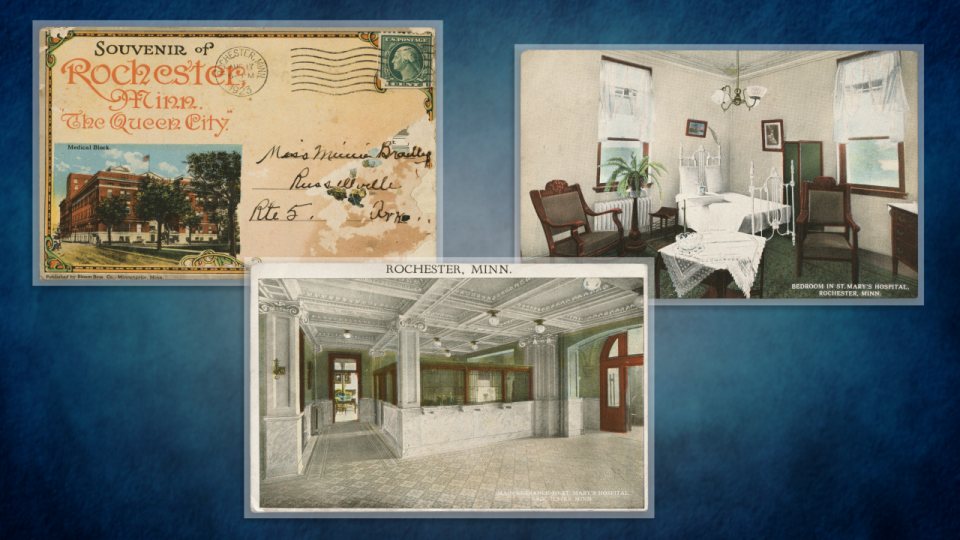

In the early 20th century, collecting postcards was a national craze. Nearly a billion picture postcards were mailed in the U.S. in 1913. Visitors to Rochester found many to choose from in the local shops, including colorized photos of interiors and exteriors of Mayo buildings, local landmarks and even doctors’ homes. Today, they provide an intriguing glimpse at how Mayo Clinic looked in times gone by.

Mayo Clinic commissioned the construction of a life-sized, see-through human figure for exhibition at the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago. A ten-minute recorded lecture played as internal colored lights directed attention to various organs. Today, the Transparent Man can be seen in the Barbara Woodward Lips Patient Education Center in Rochester.

True Comics ran a two-part series on the origins of Mayo Clinic in 1943. While the visualizations are fanciful, the story depicted here is true. As boys, Will and Charlie Mayo really did accompany their father on his rounds and assist in “kitchen table operations.”

Howard F. Polley, M.D., was a member of the Mayo Clinic team that developed cortisone in the 1940s. Dr. Polley was an avid collector of cartoons about the clinic or featuring the Mayo name. He developed friendships with many cartoonists who sometimes sent him inscribed originals. The collection, which Dr. Polley donated to Mayo Clinic, includes this panel from a Dick Tracy comic by Chester Gould.

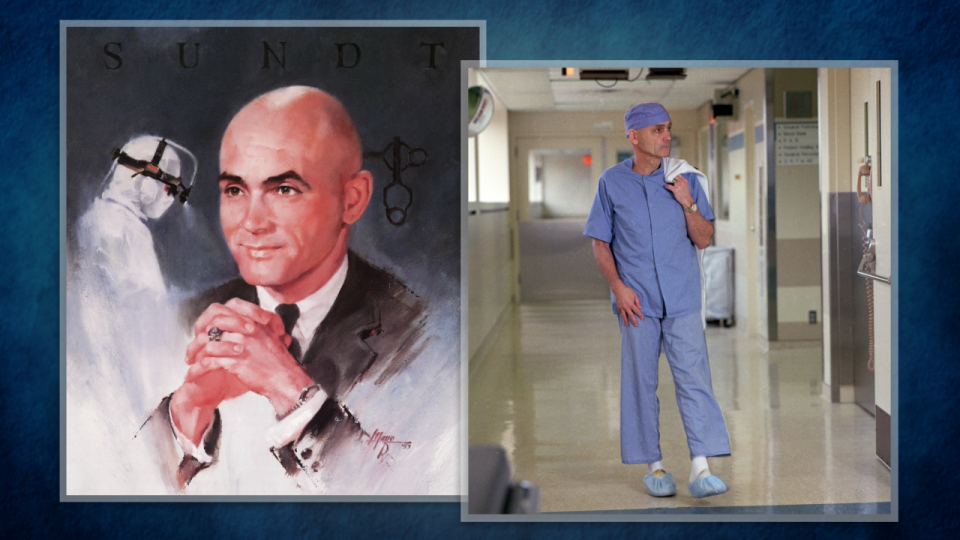

Thoralf M. Sundt, M.D., was a surgeon on the staff of Mayo Clinic from 1969 to 1992. He was internationally recognized for his many contributions to the specialty of neurosurgery and counted President Ronald Reagan among his patients. In 1991, Lesley Stahl interviewed Dr. Sundt for the television newsmagazine “60 Minutes.” He courageously continued serving patients until two months before his death from multiple myeloma.

Franciscan Sisters and a family of physicians create a legacy of care in La Crosse, Wisconsin.

Go behind the scenes to learn more about the unique locations and historic images featured in the film .

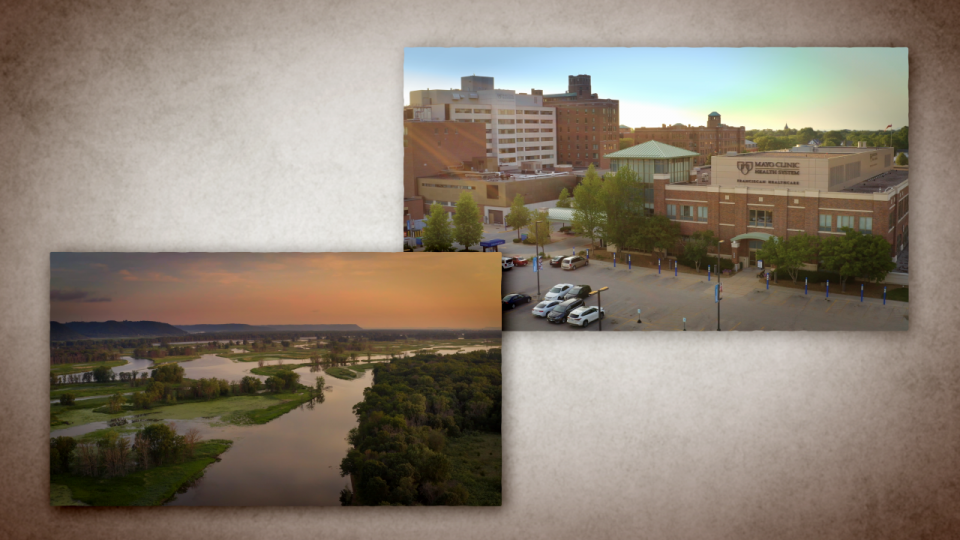

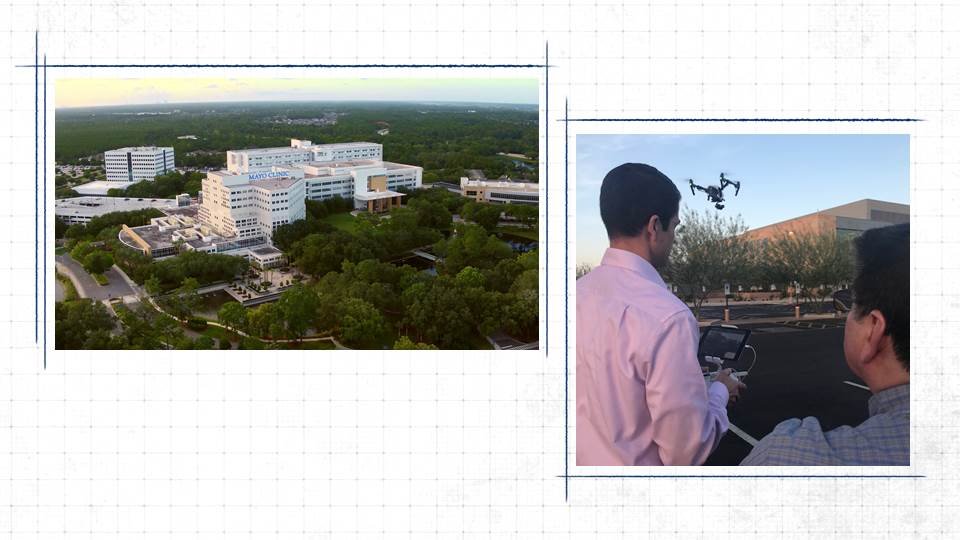

One of Mayo Clinic’s licensed drone pilots captured dramatic images of the beautiful Coulee Region in which La Crosse, Wisconsin, is located and a bird's-eye view of the campus of Mayo Clinic Health System – Franciscan Healthcare. Filming took place at sunrise and sunset to capture the attractive light that filmmakers call “golden hour.”

Filming took place by special permission in the Mary of the Angels Chapel at the St. Rose Convent, home of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration. Consecrated in 1906, the chapel is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

The Perpetual Adoration Chapel is adjacent to the Mary of the Angels Chapel. Prayers are offered continuously from 6:00 AM to 10:00 PM, seven days a week. To avoid disruption, filming was accomplished from the upper level.

Images of some of the many decorative elements of the Mary of the Angels Chapel are used throughout the film to represent the sisters’ spiritual journey. Special instruments were used to cast light on paintings in the upper reaches of the chapel.

The two chapels have over one hundred windows created by the Royal Bavarian Stained Glass Factory in Munich, Germany. They were recently cleaned and restored by a Wisconsin artisan. This window depicts one of the sisters’ primary missions, education.

This wooden altar was constructed in 1872 for an earlier chapel the sisters built in La Crosse. When the current chapel was built, the altar was donated to a Catholic hospital in Sparta, Wisconsin. It was returned in 1941 and now serves as a reliquary altar.

Because of fire regulations, candles could not be lit in the reliquary chapel. The crew filmed the altar and displayed it on the large videowall in the Mayo Clinic studio. Candles were filmed in front of the videowall to illustrate the practice of Perpetual Adoration in the 19th century.

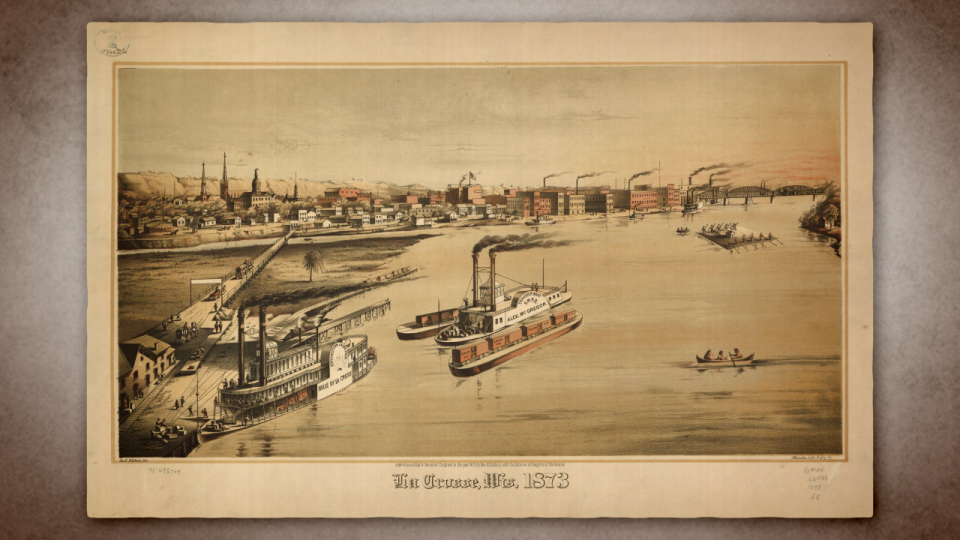

Visuals were obtained from many sources, including the archives of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration and the La Crosse Public Library. This view of La Crosse is from the Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division. It depicts the city two years after the sisters arrived.

This watercolor of the sisters’ convent in Nojoshing, Wisconsin is a rare contemporary view of the congregation’s early days. It was painted in 1866 by a student at the seminary which Bishop Henni located next to the convent.

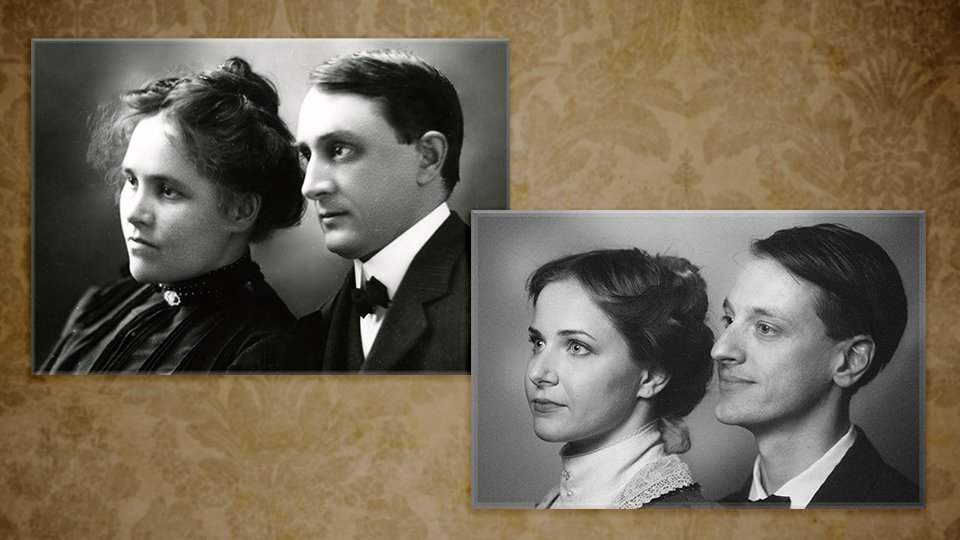

The children and other descendants of Drs. Archie and George Skemp provided photos from their family albums for the film. The photo on the left is of Archie and his wife, Ellen; the one on the right is of George and his wife, Mary on their wedding day.

This rare photo of the clinic where Drs. Archie and George Skemp practiced was badly faded. The graphic designer brought it back to life for the film. She also removed parking meters and other contemporary elements.

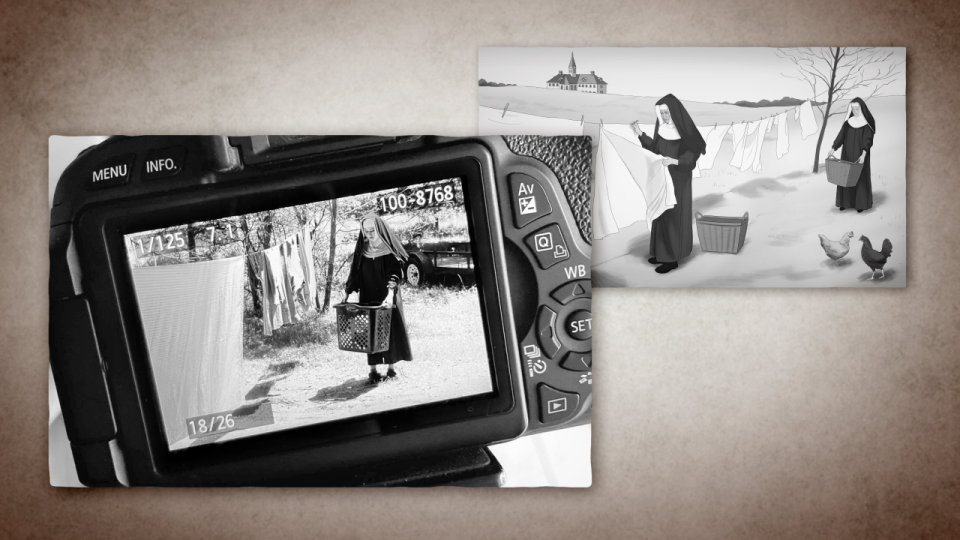

A Mayo Clinic medical illustrator created drawings for key moments in the story for which period images were not available. For an illustration of the pioneer sisters at work, the artist’s daughter posed in his back yard.

After the film was edited, music was specially composed and created for the soundtrack. The composer used an electronic synthesizer to play orchestral strings, woodwinds, horns, percussion instruments, a pipe organ and more.

An Italian physician comes to Mayo Clinic for training and makes lasting contributions to open heart surgery.

This film honors Dr. Giancarlo (Gian) Rastelli, a surgeon from Italy who made enduring contributions to the treatment of heart disease before his untimely death from cancer in 1970.

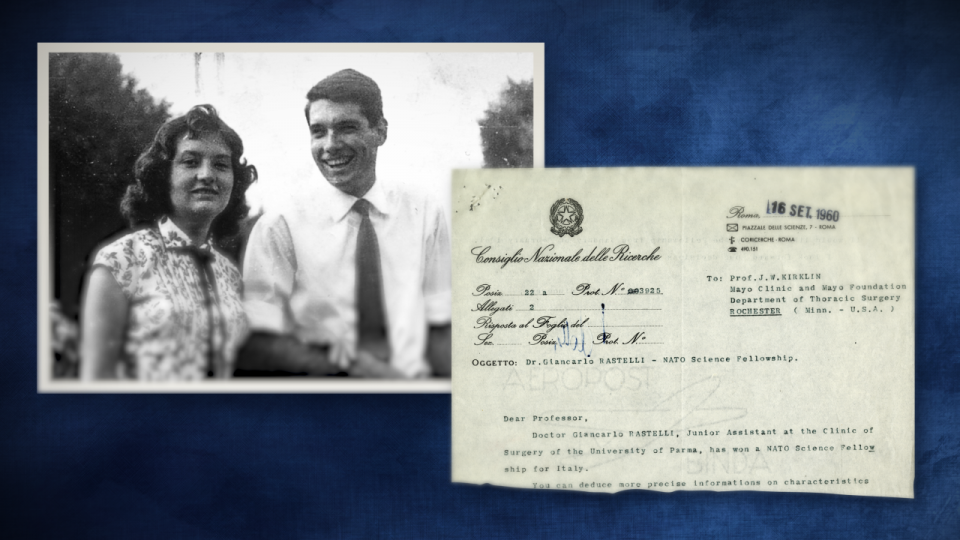

Gian, seen here with his sister Rosangela in Parma, Italy, received a NATO fellowship shortly after earning his medical degree. He chose to study at Mayo Clinic. This letter introduced him to Dr. John Kirklin, a Mayo pioneer in open-heart surgery. Gian arrived in Rochester, Minnesota, on October 1, 1961.

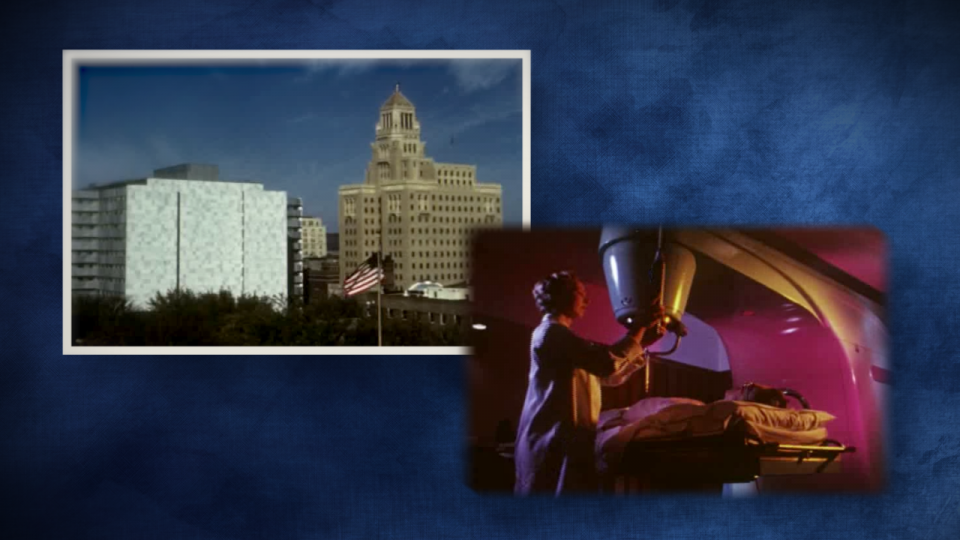

To capture the ambience of the clinic in Dr. Rastelli’s day, the filmmakers used footage from a 1964 film produced for Mayo Clinic’s centennial celebration. The photo above shows the Mayo Building (left) as it looked during Dr. Rastelli’s time at Mayo Clinic, before ten stories were added. Dr. Margaret Holbrook is seen operating a cobalt-60 radiotherapy machine.

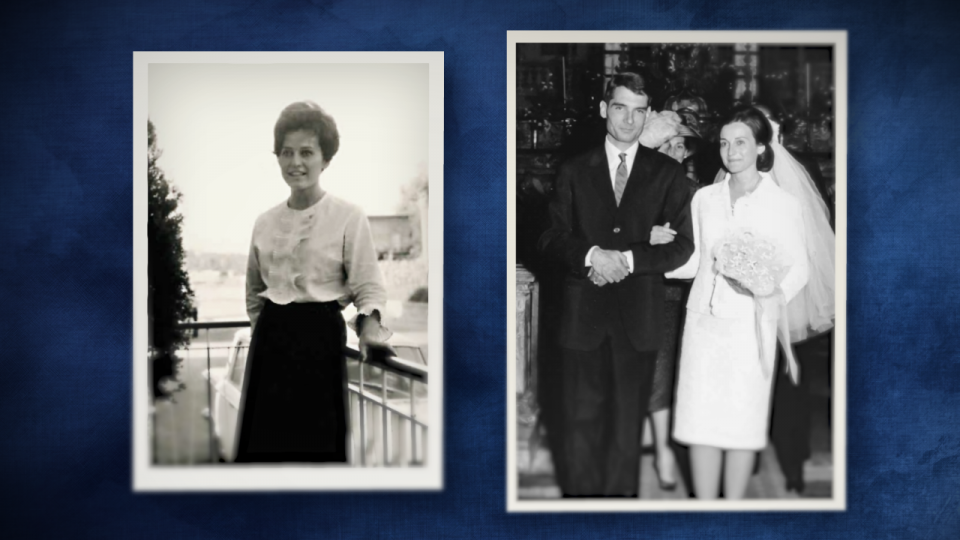

When his fellowship ended, Gian accepted a staff position at Mayo Clinic. In the summer of 1964, he traveled to Italy to marry the love of his life, Anna Anghileri. Following their honeymoon, the newlyweds returned to Rochester. These and other photos were made available for the film courtesy of the Rastelli family.

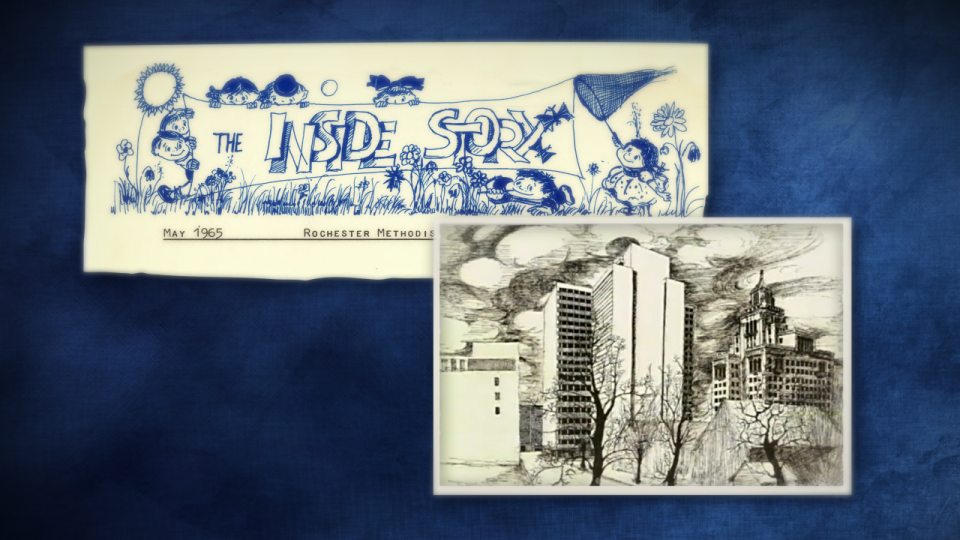

Anna was a talented artist. She created drawings of their new home, taught at the Rochester Art Center, and contributed artwork for the Rochester Methodist Hospital newsletter.

Gian and Anna’s daughter, Antonella, was born in Rochester. Today, she is a physician who practices in Italy. Dr. Antonella Rastelli has visited Mayo Clinic to conduct research and give presentations about her father. In the photo at right, Dr. Antonella Rastelli is seen with Dr. Andrea Mariani (left) and Dr. John Stulak (center) of Mayo Clinic.

During the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, the crew followed strict safety protocols in filming and post-production.

Scenes recreating the 1960s were filmed in a studio at Mayo Clinic, using period photographs on a videowall as backdrops.

The film includes wax models that Dr. Rastelli used to demonstrate his research on heart defects. Karen Koka of the W. Bruce Fye Center for the History of Medicine handled these delicate artifacts during filming.

Dr. Joseph J. Maleszewski, a cardiac anatomic pathologist at Mayo Clinic, confirmed these wax models are from a 1968 exhibit on Dr. Rastelli’s research. The exhibit won a gold medal from the American Medical Association. Dr. Rastelli (far left) is seen with his Mayo Clinic colleagues Dr. Dwight C. McGoon (center) and Dr. Jack L. Titus.

The stained glass window seen in the film is located at Mayo Foundation House, the former home of Dr. and Mrs. William J. Mayo. It depicts 2,000 years of medical progress.

Gian was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1964. Despite the rigors of treatment, he continued living a productive and happy life until his death at Rochester Methodist Hospital in 1970 at the age of 36. This scene was filmed at the hospital and composited with a stock photo to represent the view from the hospital at the time Dr. Rastelli was a patient there.

Soon after his death, colleagues dedicated a plaque to Dr. Rastelli. More than 50 years later, it has a place of honor in a cardiology staff library at Mayo Clinic.

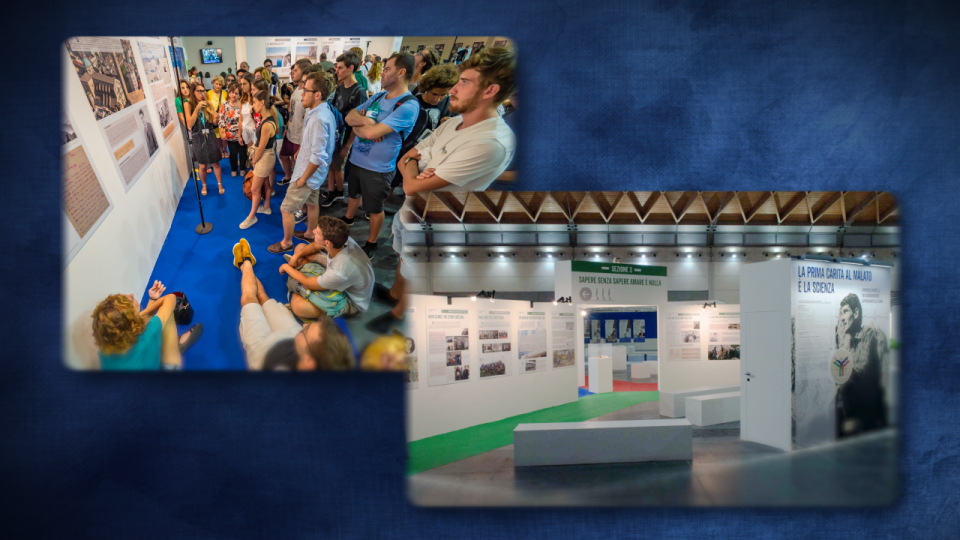

In 2017, a group of Italian medical students, intrigued by the story of the man behind the name in their textbooks, created an exhibit on Dr. Rastelli’s life and work. It has traveled internationally to widespread interest and acclaim.

The medical students and Dr. Antonella Rastelli collaborated on a biography of her father, which was published in Italy. They worked with colleagues at Mayo Clinic to publish an English translation, which was an important source for the film. This international group worked together for more than a year to prepare these inspiring tributes to Dr. Giancarlo Rastelli, sharing his enduring message that science is an act of love.

Researchers find a clue hiding in plain sight that may lead to a breakthrough in treating a painful condition.

The first professional nurse at Mayo Clinic becomes Dr. Charlie’s wife, a community leader and a devoted mother and grandmother.

This film was a collaboration of more than 100 people, including production professionals, actors, historians, subject matter specialists and others.

A corner of the 16th floor of the historic Plummer Building at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, made an appropriate background for laboratory recreations. It has changed little since the building opened in 1929. Currently used for library storage, it was originally an endocrinology laboratory, the medical specialty concerned with hormones—including cortisone.

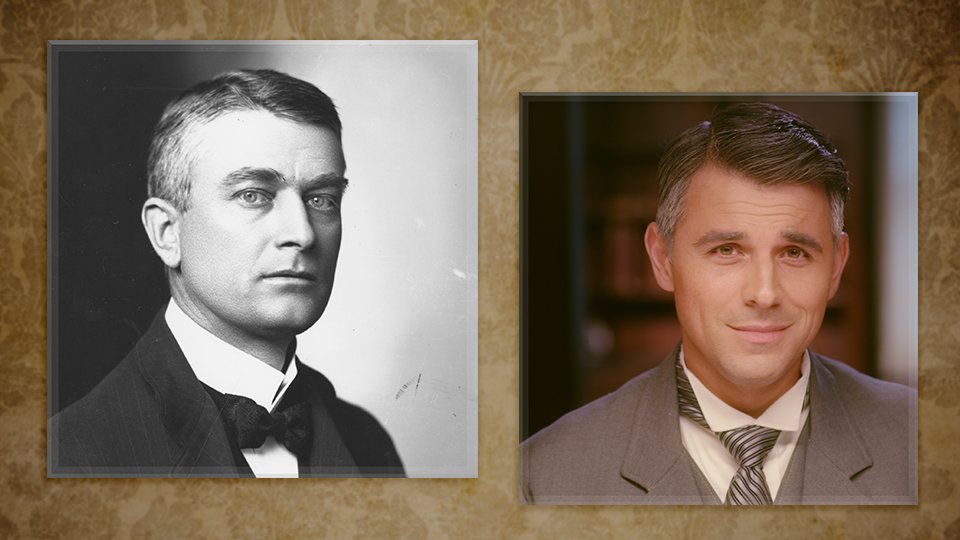

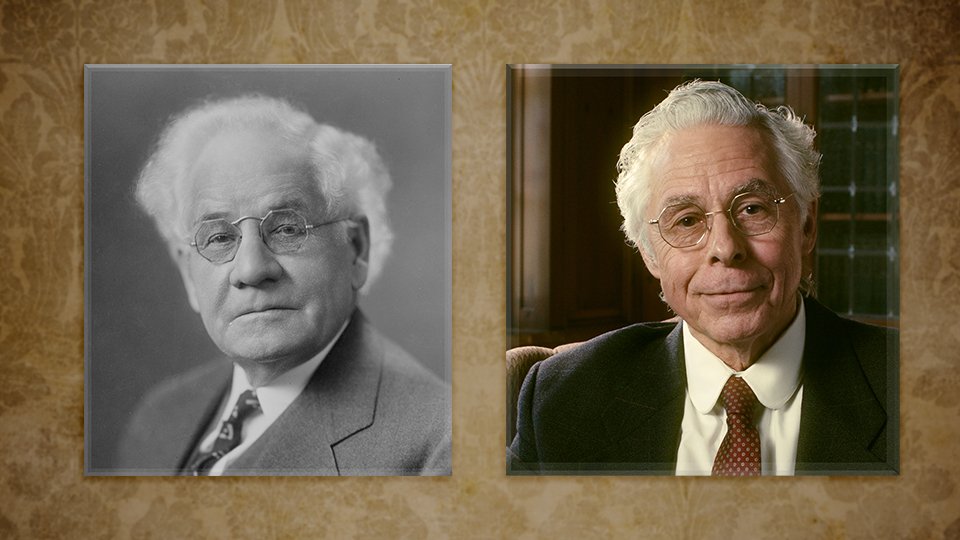

Edith and Dr. Charlie are played in their early years by Christina Stier and Blake Hogan.

Edith and her husband, Dr. Charles H. Mayo, are played in middle-age by Anna Lakin and Ari Hoptman.

Cynthia Hayden plays Edith in 1942, at age 75.

Sally Wingert plays Sister Fabian Halloran, one of the pioneering Sisters at Saint Marys Hospital.

Bill McCallum plays Charles W. Mayo, M.D., Edith’s eldest son, a surgeon at Mayo Clinic.

Pam Captain plays Hattie Damon Mayo, the widow of Dr. William J. Mayo.

Dr. William J. Mayo, Edith’s brother-in-law, is played by Sasha Andreev.

Michelle Barber plays Anna Neumann, who was part of the Mayo family’s household staff for almost 40 years.

Edith’s favorite brother, Dr. Christopher (Kit) Graham, is played by Richard Dietman.

With help from the make-up artist, Mayo Clinic employee Marv Mitchell was transformed into Dr. William Worrall Mayo.

Mayo Clinic employee Kathy Shepel fabricated many of the paper props seen in the film, re-creating historic documents too fragile or valuable to leave the Mayo Clinic archives.

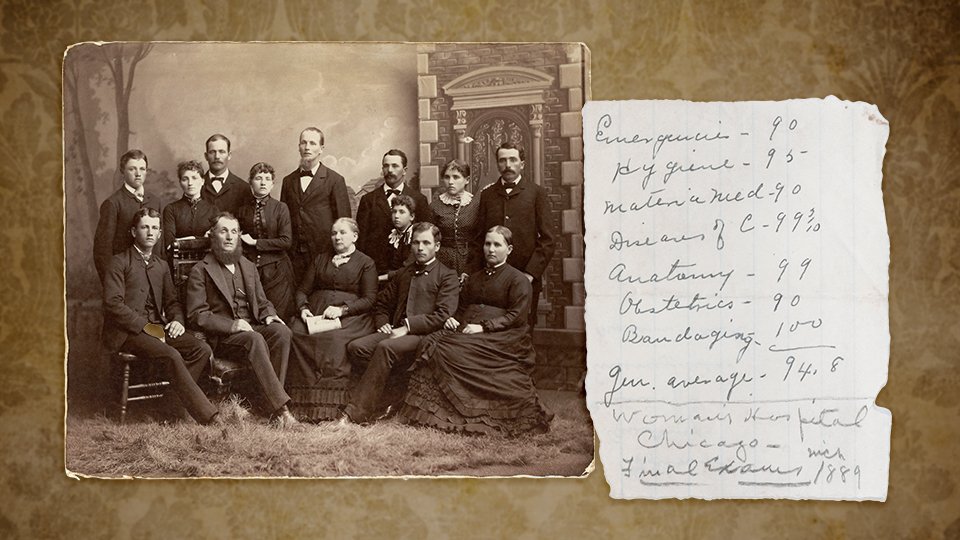

The artifacts she re-created include this artificially aged photo of the Graham family and a scrap of paper containing Edith’s final grades from nursing school.

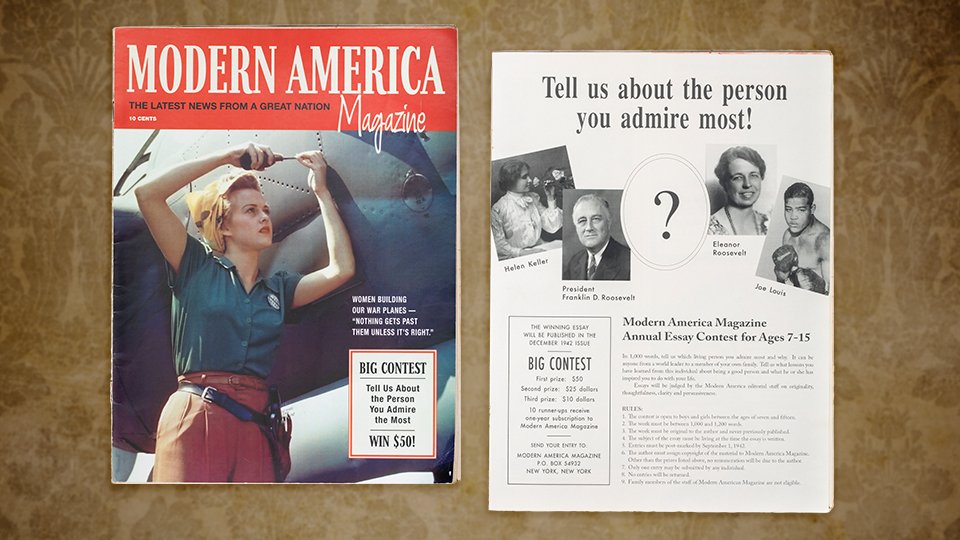

She designed a wartime cover of the fictional “Modern America” magazine, as well as the page describing the essay contest on which the plot of the film turns.

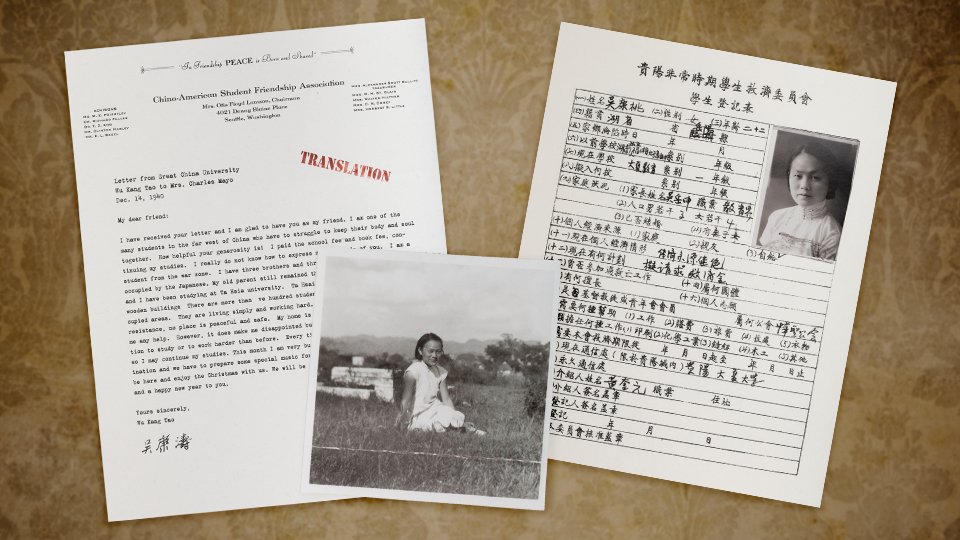

She re-created documents and photographs related to Edith’s sponsorship of a student in China.

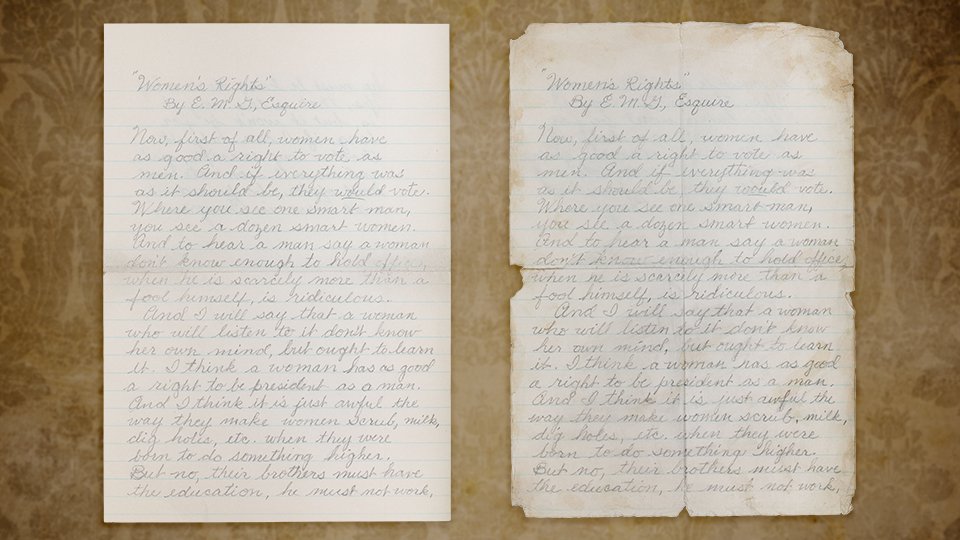

Two versions of Edith’s school essay were created: one for a scene set in the 19th century and another as it might have looked 60 years later.

The History Center of Olmsted County loaned the filmmakers a replica of the medal presented to Edith as American Mother of 1940.

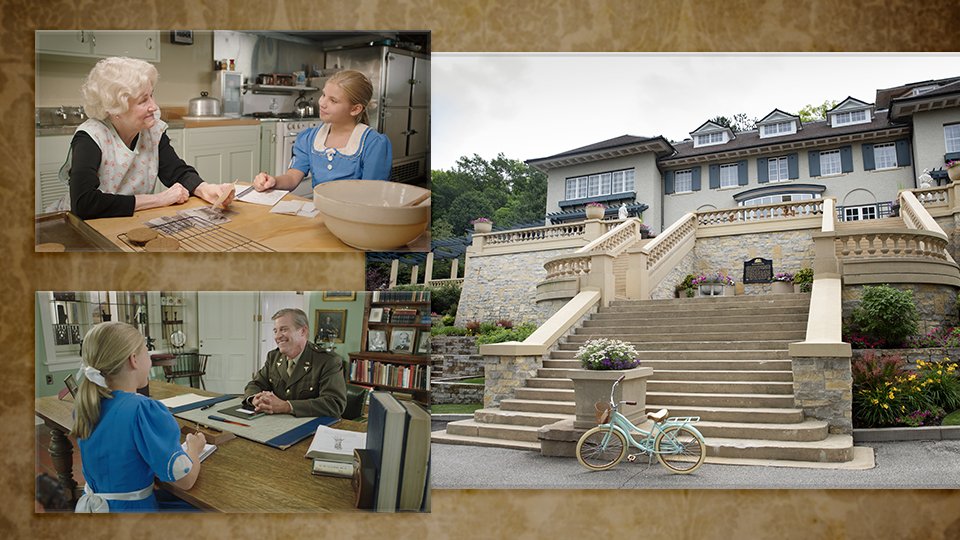

The bicycle ridden by Ruby Palmer as Mayo Trenholm is a vintage-style contemporary model adapted by the filmmakers.

The nursing uniform made for the film was closely modeled on Edith Graham’s graduation photo.

Sister Mary Goergen helped ensure the historical accuracy of the habit worn by Jeryl Mitchell, portraying one of the Franciscan Sisters trained by Edith Graham.

A variety of historic locations are seen in the film, including the Mayo Clinic Historical Suite in the Plummer Building.

Several scenes were staged in the former kitchen of Saint Marys Hospital.

Scenes were filmed at Assisi Heights, the motherhouse of the Sisters of St. Francis of in Rochester, MN.

A number of interior and exterior scenes were filmed at Mayowood, the former home of Dr. Charlie and Edith.

The scene featuring Hattie Mayo was filmed in the dining room of a former home of Dr. Will and Hattie.

The scene of Mayo arriving at Saint Marys Hospital to visit Sister Fabian was filmed at the former main entrance to Saint Marys Hospital.

The scene of Edith attending a 19th century medical meeting was filmed in Goldstein Hall in the Guggenheim Building at Mayo Clinic.

The authentic one-room schoolhouse at the History Center of Olmsted County was the setting for Edith presenting her essay on Women’s Rights. Rochester children played her classmates.

For a scene of Dr. Charlie and Edith washing dishes, the actors, the kitchen and the house were filmed in different locations and combined in post-production.

Dr. Charlie and Edith are seen riding in an authentic 19th century cutter, acquired from retired Mayo Clinic employee Barbara Mestad and her husband, Roger.

For safety reasons, Steve Wood of Wildwood Sleigh and Carriage “doubled” for Dr. Charlie driving the cutter.

Rochester children portray Mayo Trenholm’s cousins in a game of Robin Hood. Many members of the Mayo family have fond memories of spending summers at Mayowood.

Art, architecture, nature and innovations contribute to a culture of healing at every Mayo site.

Go behind the scenes to discover interesting facts about the people, places, artwork and historical artifacts featured in this film.

More than 250 employees and volunteers responded to a casting call to portray patients and staff.

To support patient privacy, certain scenes in public spaces were filmed after hours and on weekends.

Mayo Clinic’s licensed drone pilots captured birds-eye views of Mayo sites in Arizona, Minnesota and Florida (pictured here.)

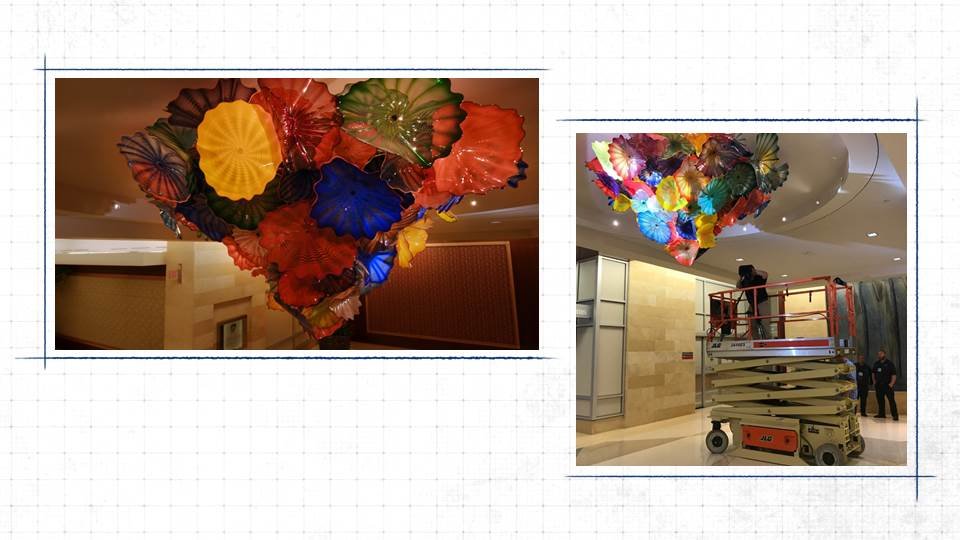

A scissor lift raises the camera for a striking view of the “Mayo Clinic Persian Chandelier” by Dale Chihuly in the lobby of Mayo Clinic Hospital in Florida.

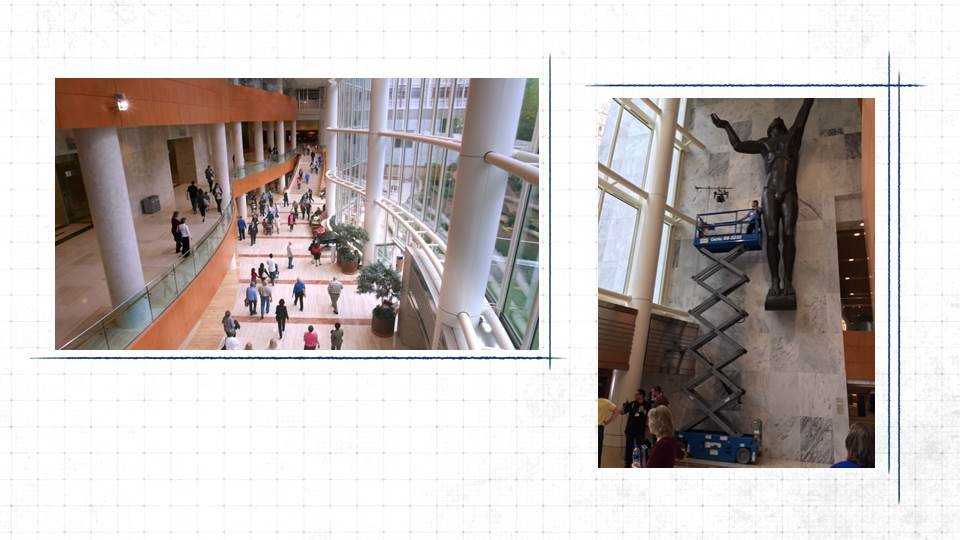

This image shows what Landow Atrium in the Gonda Building in Rochester, Minnesota, looks like from the perspective of the iconic “Man and Freedom” sculpture.

A small GoPro camera was affixed to an Electric Track Vehicle, capturing a view of its journey through the ceilings of buildings on the Mayo campus in Rochester.

This restored 1875 train depot is located in Minnehaha Park in Minneapolis. For the re-creation of a 19th century patient coming to Mayo Clinic, crates and luggage were arranged to block the view of road signs and traffic. A model train car was added in post-production, along with a burst of steam.

For the re-creation of a family traveling to Mayo in the 1960s, a Minnesota collector provided a perfectly restored 1963 Oldsmobile station wagon.

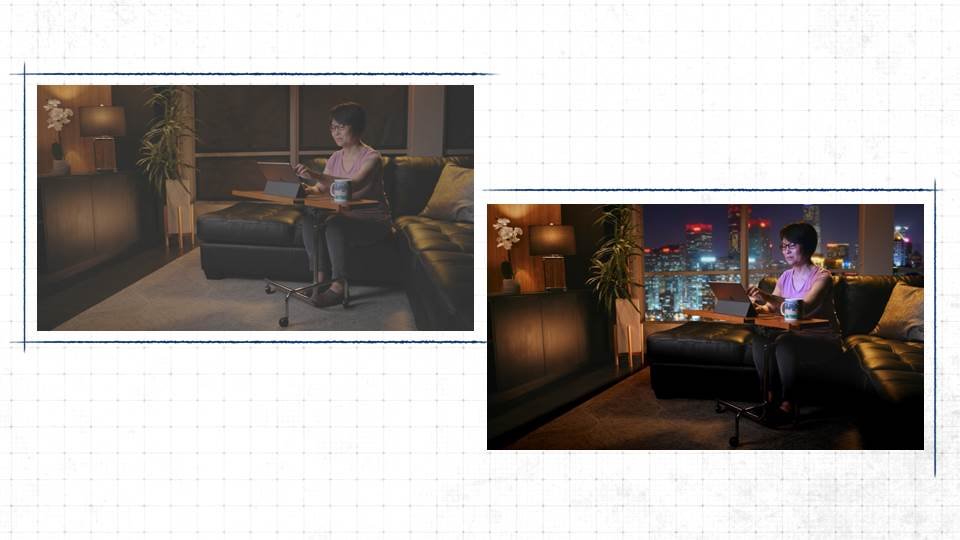

This scene features Mayo employee Jingfei Cheng portraying an international patient planning her visit to Mayo Clinic. It was filmed on the top floor of an apartment building in Rochester; the cityscape behind her is a stock photo added in post-production.

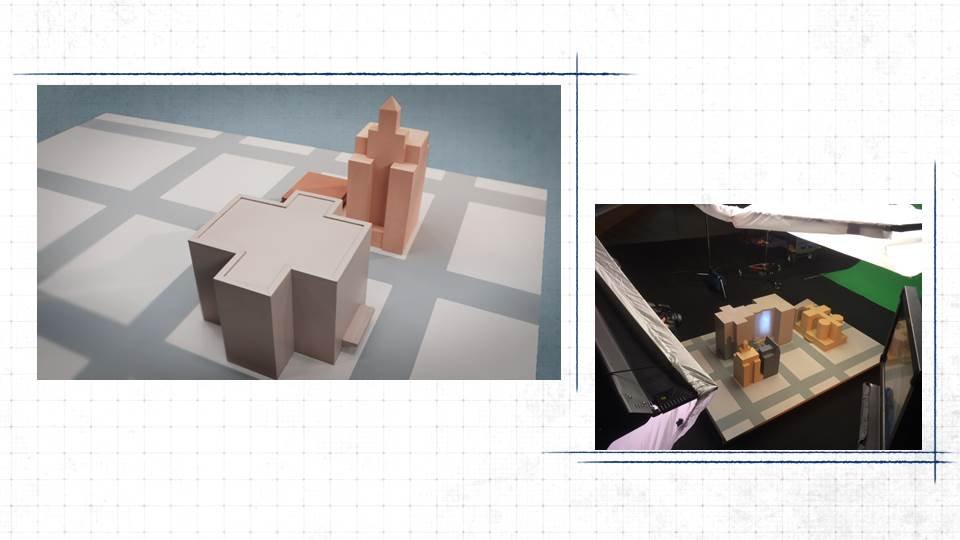

Mayo Clinic carpenter Michael P. Johnston created an accurate scale model depicting the growth of Mayo buildings in downtown Rochester between 1914 and 2001.

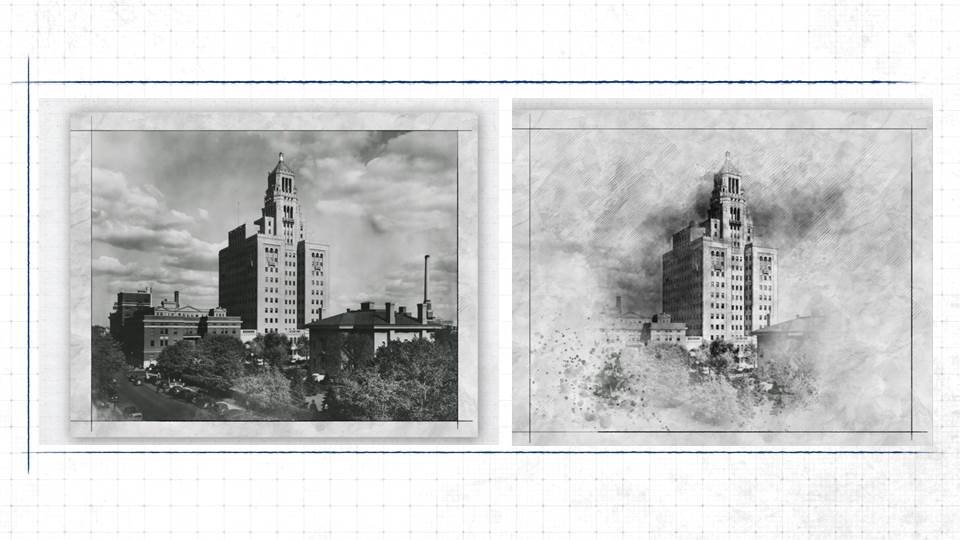

The graphic designer used software to create “architectural renderings” from archival photographs of Mayo buildings, including the iconic Plummer Building.

To capture the Christmas tree appearing on the Plummer Building at twilight, the cameraman set up a two-hour motion-controlled time-lapse shot on the roof of a building across the street.

The distinctive glass “wave wall” of the Gonda Building is echoed in the lobby of the Mayo Clinic Building in Phoenix.

Luther Hospital and the Luther Building at Mayo Clinic Health System in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, are named for the hospital that began providing medical services to the community in 1908.

This view from Annenberg Plaza in Rochester shows how the design of the 1989 Siebens Building (left) pays homage to its neighbor, the 1928 Plummer Building.

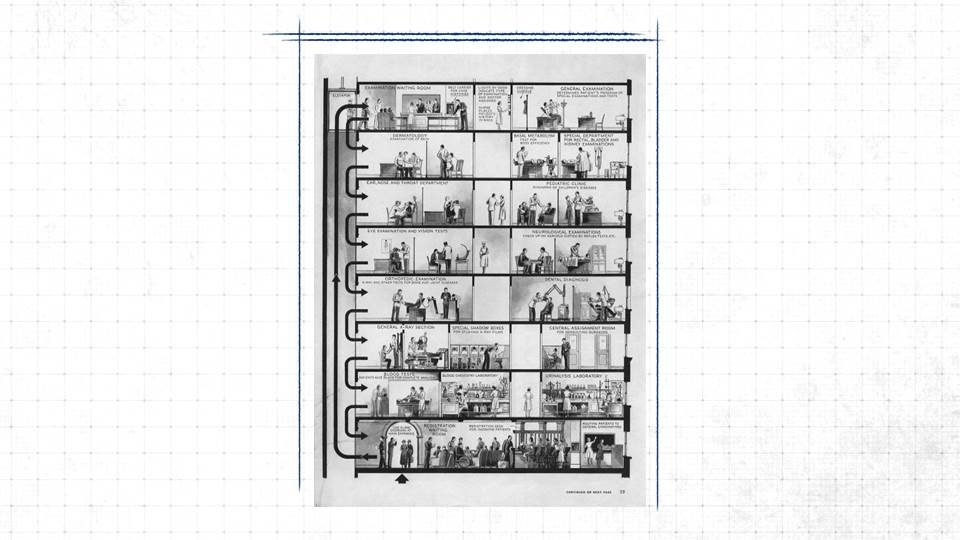

This cutaway drawing of the Plummer Building, illustrating Mayo’s patient-centered efficiency, appeared in a 1939 Life Magazine article.

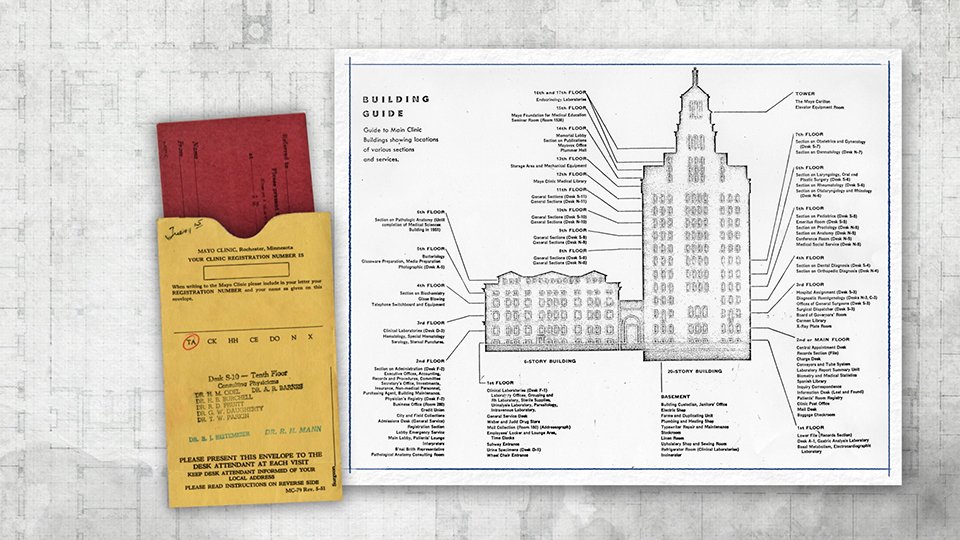

Color-coded cards and this guide were given to patients to help direct them to their appointments in the Plummer and 1914 buildings. These items are from the archives of the W. Bruce Fye Center for the History of Medicine.

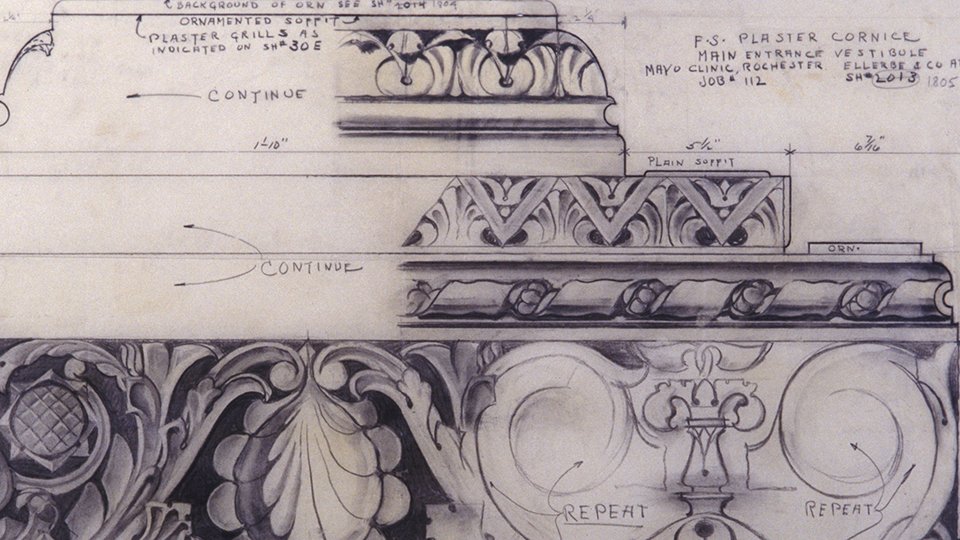

This detailed illustration of ornamentation on the Plummer Building was hand-drawn by an employee of the architectural firm Ellerbe and Company in the 1920s.

The tower of the Plummer Building is decorated with Romanesque stone carvings. The griffin, part eagle and part lion, symbolizes vigilance and strength.

The bronze doors of the Plummer Building are 16 feet tall and weigh more than two tons. They were designed by Ray Corwin of Ellerbe & Company and sculpted by Charles Brioschi, a St. Paul artist.

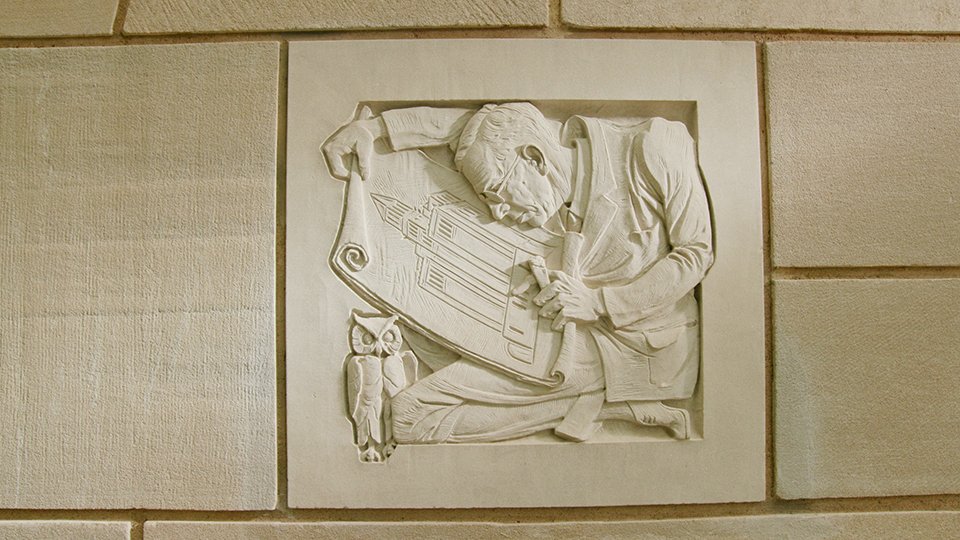

Near the bronze doors of the Plummer Building, a stone carving depicts Dr. Henry Plummer examining the architect’s plans. It features an owl, symbolizing wisdom, and Dr. Plummer’s omnipresent cigar.

The floor in the Plummer Building lobby is made of art marble, a mixture of marble chips and colored cement. The intricate designs feature seven colors of marble from Algeria, Belgium, Italy and Pennsylvania.

The ceiling of the Board of Governors Room, located in the Historical Suite on the third floor of the Plummer Building, features molded plaster and gold polychrome.

This corridor of the Richard O. Jacobson Building in Rochester shows how stone, glass, wood and artwork combine to create a warm, enduring environment in contemporary Mayo buildings.

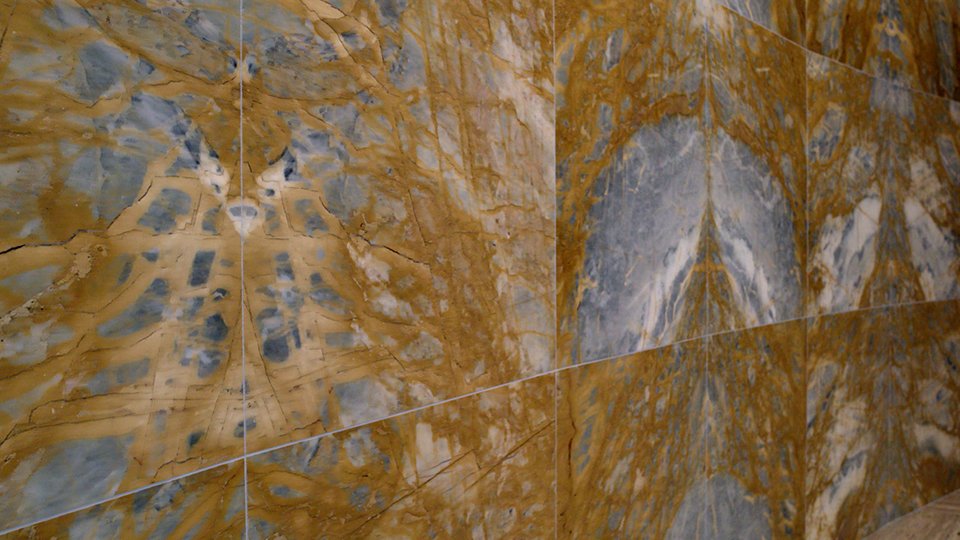

The beautiful polished Esmeralda onyx chosen for the lobby of the Jacobson Building was quarried in the Middle East.

This travertine, formed in a hot spring in Italy, is similar to the materials used in the Roman Coliseum. Travertine is one of the most widely used stones on the Rochester campus.

The exterior of the Mangurian Building in Jacksonville, Florida, features Danby marble, quarried in Vermont. The same stone was used on the exterior of the Gonda Building.

These contrasting stones were chosen for both the exterior and interior of the Mayo Clinic Building in Scottsdale, Arizona. The look and feel of sandstone is very appropriate for a campus in the Sonoran Desert.

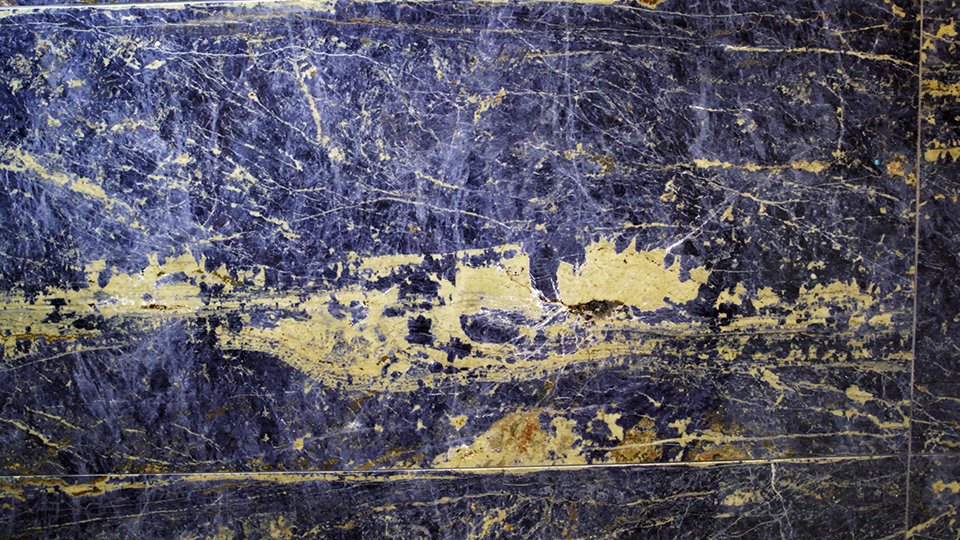

The Black Marinace in the 12th floor waiting area of the Gonda Building was quarried from an ancient river bed in Brazil. Marinace is a stone comprised of a variety of rocks, fossilized by extreme temperatures and high pressure.

This striking gold-colored marble was installed in the Mathews Grand Lobby in the Mayo Building in Rochester using the “bookmatching” technique. The slabs are finished and arranged so the veins and patterns of adjacent blocks mirror one another.

According to legend, blue sodalite from Brazil has calming and even healing properties. It can be found in the Stephen and Barbara Slaggie Family Cancer Education Center in the Gonda Building and in the second floor lobby of the Mangurian Building.

“Boy with a Dolphin” was designed by David Wynne to convey a sense of joy and well-being. This popular sculpture was installed next to the Mayo Building in Rochester in 1984.

The architectural installation “Cycles of Life” by John Richen features a reflecting pool and three circular forms, representing patient care, education and research. It’s located on the concourse level of the Mayo Clinic Building in Scottsdale.

The world-renowned glass artist Dale Chihuly created an installation for the Mayo Nurses Atrium in the Gonda Building. Its 13 chandeliers contain 1,375 pieces of glass.

This bronze sculpture of St. Francis looking up through Brother Sun is by the Minnesota sculptor Paul Granlund. It greets visitors to the hospital at Mayo Clinic Health System in Mankato, Minnesota.

This seven-foot bronze figure of Jean D’Aire was a study made by Auguste Rodin for his famous sculpture, “The Burghers of Calais.” It stands in Hage Atrium in the Siebens Building in Rochester.

The lobby of the Mayo Clinic Building in Phoenix features a scale model of the “Mayo Ancestors” statue by Glenna Goodacre and a Mayo ambulance made by the Studebaker Company in 1905.

“Man and the Energies,” by William Saltzman, is one of a series of murals commissioned for the Mayo Building in Rochester on the theme “Mirror to Man.” While many of the murals have been covered, this one is still visible on the third floor.

The luminous 15-foot painting “Give Me Wings” by Susanne Schuenke depicts butterflies in oil and gold leaf on linen. It hangs in the lobby of Mayo Clinic Hospital in Florida.

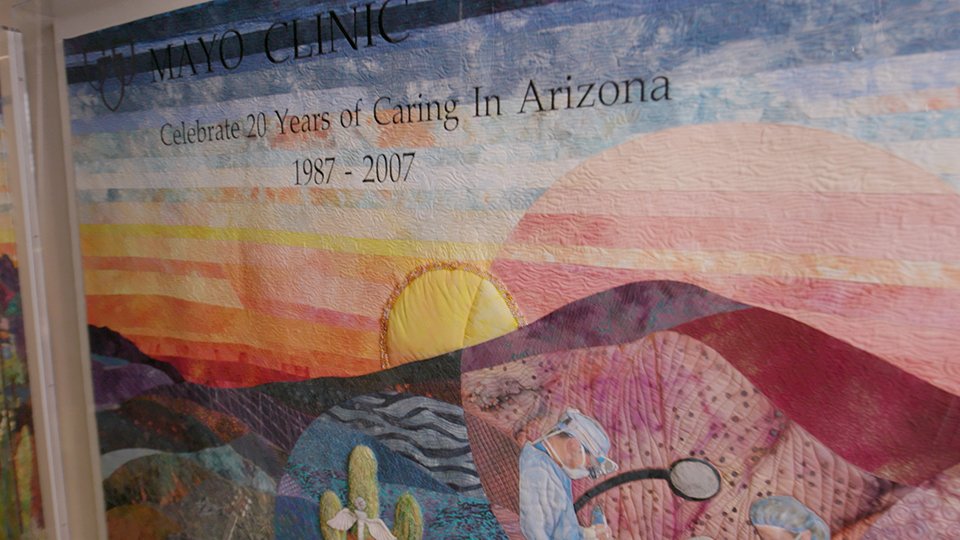

Dr. Renee E. Caswell led artist Denise A. Currier and a team of Mayo Clinic Arizona employee volunteers in the two-year process of creating this 13 x 5-foot quilt to commemorate the 20th anniversary of Mayo Clinic in Arizona. It’s displayed on the concourse level of the Mayo Clinic Building in Scottsdale.

Hand-carved Hopi Katsina dolls depict helpful messengers from the spirit world. This group is displayed on the concourse level of the Mayo Clinic Building in Scottsdale.

This tabletop from Agra, India, was created by inlaying semiprecious stones in white marble, a technique developed in ancient Greece and Rome. It’s displayed in the 17th floor elevator lobby of the Gonda Building.

These beautiful stained glass windows were carefully removed and stored when the old chapel of St. Francis Hospital in La Crosse, Wisconsin, was demolished. They are now installed behind the altar of the hospital chapel of Mayo Clinic Health System – Franciscan Healthcare.

The chapel at Mayo Clinic Hospital, Methodist Campus in Rochester features a “rose window” based on those found in many Gothic cathedrals.

This art glass ceiling by Canadian artist Eric Wesselow decorates the Islamic prayer room in the Center for the Spirit, located in the subway of the Mayo Building in Rochester.

The art glass wall, “Healing Garden,” is in the Cahill Meditation Atrium on the first floor of the Cannaday Building in Jacksonville.

A peaceful multi-faith chapel is located near the entrance of Mayo Clinic Hospital in Phoenix.

Mass is offered daily in the Saint Marys Chapel at Mayo Clinic Hospital in Rochester. It seats more than 400 people and was designed to accommodate patients in wheelchairs and on gurneys.

The Groves Foundation Meditation Room is on the 7th floor of the Mary Brigh Building in Mayo Clinic Hospital, Saint Marys campus. It provides a peaceful environment, with light filtered through stained glass and the calming sound of running water.

The 5,000 square foot indoor Healing Garden at Mayo Clinic Health System in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, is a place for patients and visitors to enjoy greenery and sunshine, even in the middle of winter.

Louchery Island in Jacksonville provides a peaceful, beautiful setting of water, greenery, artwork and wildlife for reflection and meditation.

Visitors to the Mayo campus in Jacksonville often catch a glimpse of this snowy egret, a small white heron that has made its home on Louchery Island.

The campus of Mayo Clinic Health System in Albert Lea, Minnesota, provides serene views of Fountain Lake.

Patients and visitors to the Scottsdale campus can explore the nearby Mayo Clinic Nature Trail, a .7 mile walk through the Sonoran Desert.

These colorful plants in Feith Family Statuary Park are part of 40 acres of flower beds, shrubs and prairie grasses on the Rochester campus.

Pianos on Mayo campuses are often played by patients, visitors and employees. Carl W. Crist, a volunteer at Mayo Clinic in Florida, performs in a waiting area of the Cannady Building.

A string quartet comprised of students from Arizona State University performs a concert in the lobby of Mayo Clinic Hospital in Phoenix.

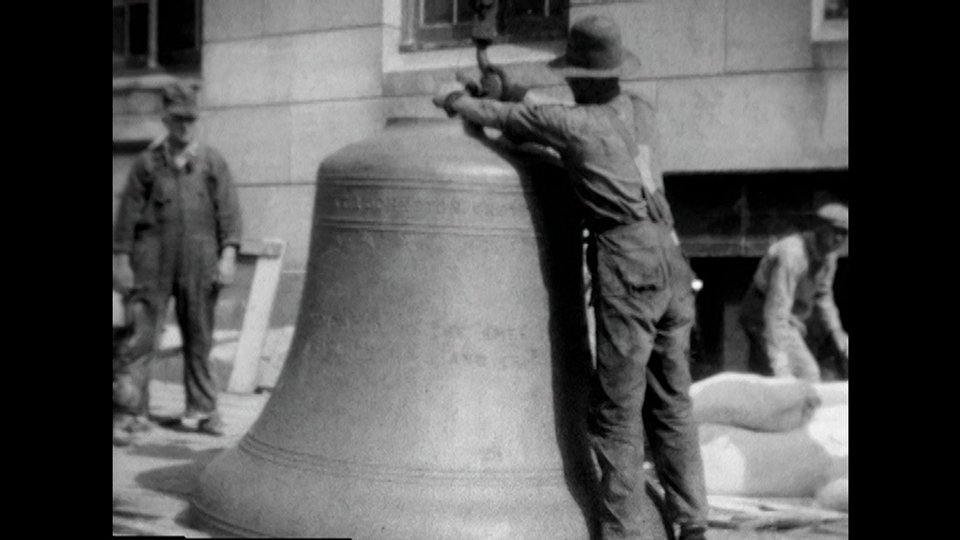

This 1928 photo shows a bronze bell, weighing almost 8,000 pounds, about to be hoisted into the tower of the Plummer Building. The Mayo brothers gifted the Rochester Carillon as a memorial to the American soldiers who served in World War I.

Austin Ferguson, the current carillonneur of Mayo Clinic, is only the fourth musician to hold that position since 1928. He operates the clavier—a console of wooden batons and pedals—in the bell tower of the Plummer Building.

This rare archival film clip shows a Franciscan Sister in the operating room at Saint Marys Hospital.

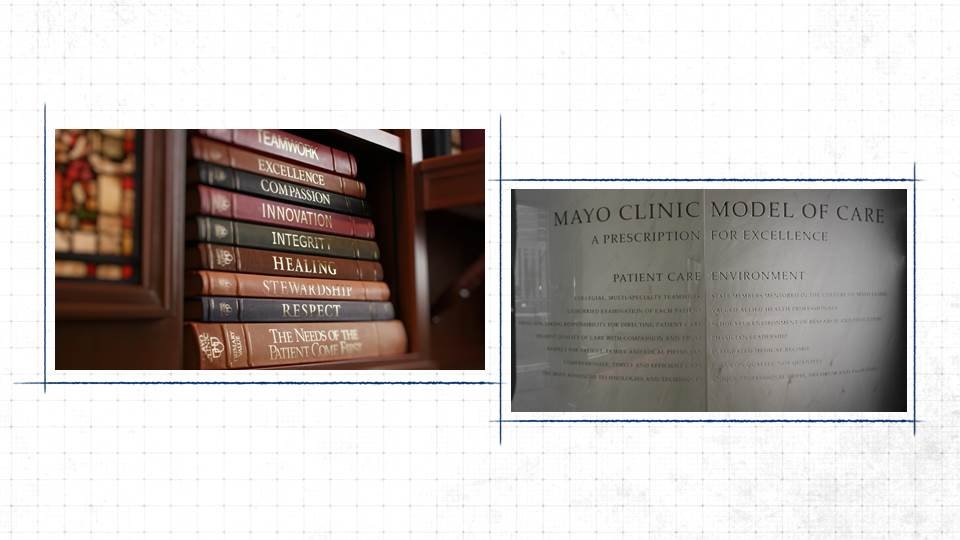

Displays in Mayo Clinic Heritage Hall, located in the Mayo Building in Rochester, provide reminders of Mayo Clinic’s mission and values. The marble engraving of the Mayo Clinic Model of Care was inspired by a similar feature in the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.

See “Where Healing Begins: The Mayo Clinic Experience” and the entire library of Mayo Clinic Heritage Films.

A family of physicians reach out to friends at Mayo Clinic to escape persecution.

A diverse group of guests at the home of Dr. Chuck and Alice Mayo discover the enduring strength of Mayo Clinic.

For the world-traveling Mayo brothers, Arizona becomes a favorite destination.

A determined woman plays an essential role in establishing the scholarly reputation of Mayo Clinic.

Meet the diversified genius who was one of the most unforgettable people in the history of Mayo Clinic.

Mayo Clinic helps protect and heal America’s warriors.

A frontier doctor and a Franciscan Sister become unlikely partners in the wake of a natural disaster.

Visit the beautiful and storied home of the Franciscan Sisters of Rochester, Minnesota.

Young Will and Charlie Mayo step in to assist their father with a difficult operation.

The true story of the beloved small-town physician featured in the movie “Field of Dreams.”

The Doctors Mayo travel the globe to learn and share the best medical practices.

A young man confined to an iron lung lives a life filled with achievement, friends and joy.

For more than a century, presidents, vice presidents and their families have come to Mayo Clinic as loyal patients, trusted advisors and generous supporters.

Dr. William J. Mayo and a small-town physician debate the future of health care delivery in 1927.

An enduring partnership of faith and science begins in 1883.

Dr. William J. Mayo and his father agree on a patient-centered approach to health care.

Dr. Will Mayo shares his love of nature with friends and colleagues through boat trips on the Mississippi River.